“WORLD peace – Victory Joy Day,” proclaimed the Echo headline on August 15, 1945.

After six hard years, the Second World War was over.

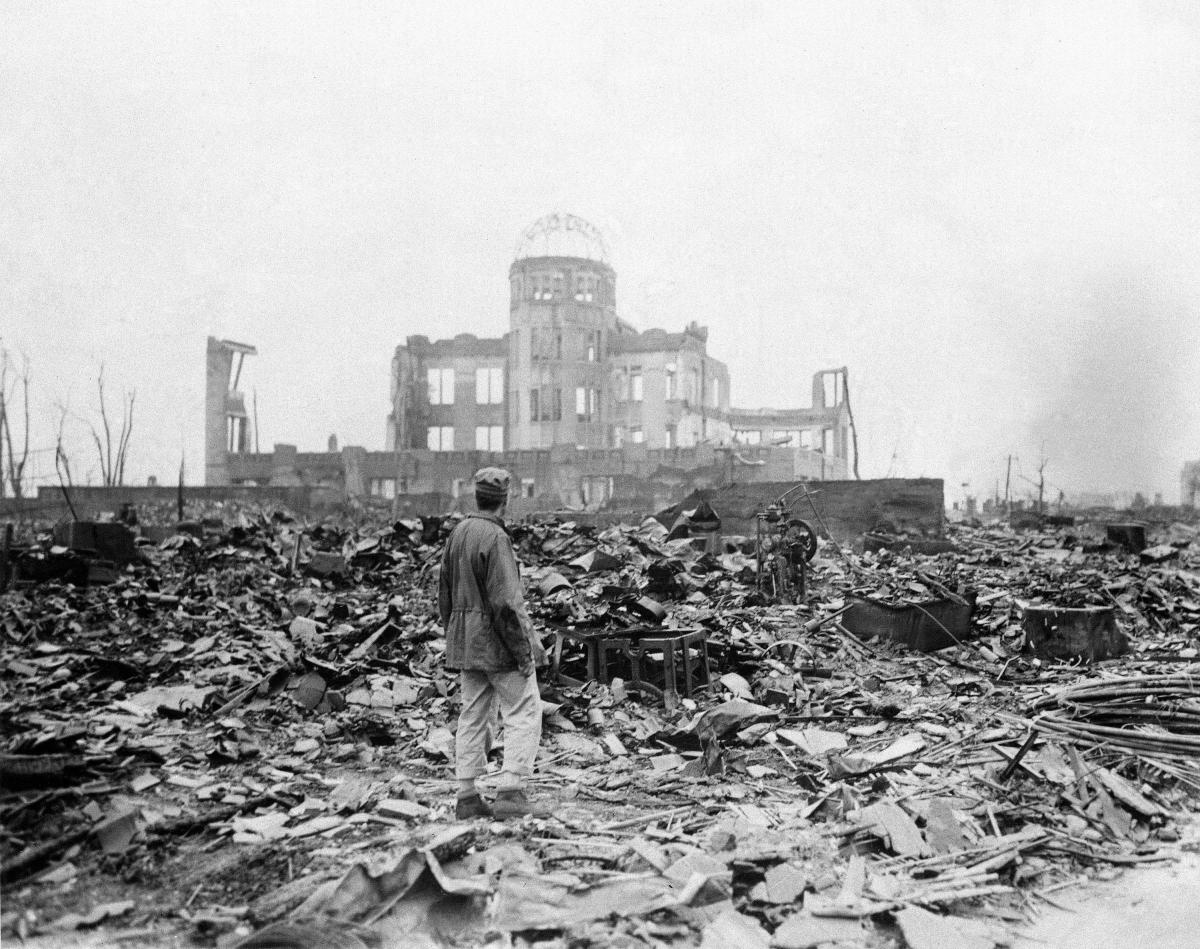

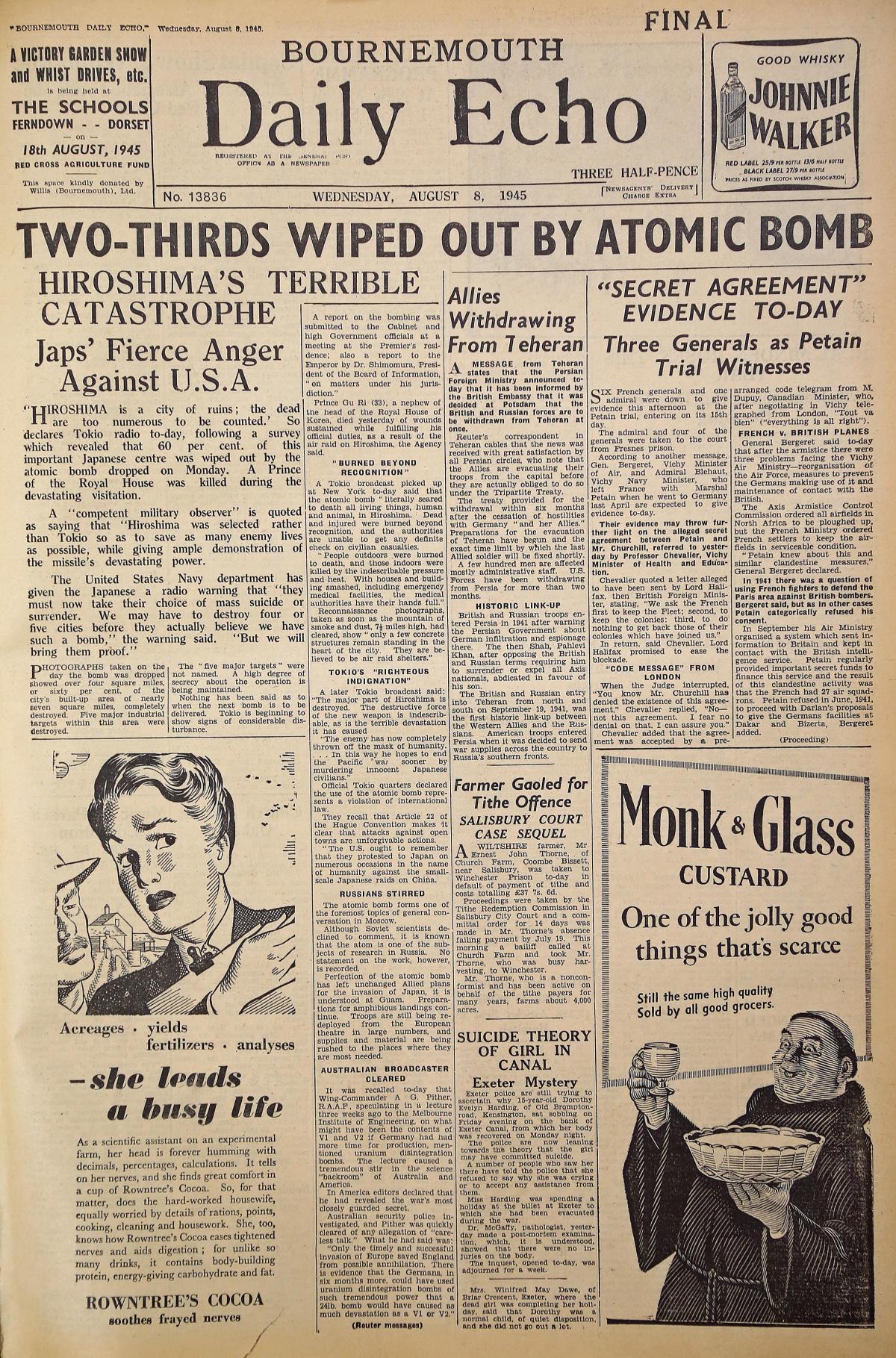

People had known for days that VJ – Victory over Japan – Day was coming. Ever since American planes dropped atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it had been clear Japan would have to surrender or face annihilation.

At midnight, Prime Minister Clement Attlee went on the radio to announce: “The last of our enemies is laid low."

The Echo reported that day: “No sooner was the news of the victory over Japan announced at midnight than celebrations began at Bournemouth.”

Festivities broke out straight away. An American band played from the top of the transport shelter in Bournemouth Square. Thousands danced around a bonfire in the road, Conga lines snaked around the Square, and jeeps drove around with horns screeching.

In Poole, the midnight announcement was greeted by a blast of sirens from vessels at the Quay, many of them lit up or decorated with bunting.

A crowd assembled in the High Street, singing, dancing, and letting off fireworks.

“The fun was kept up for some time, and even up to 3 o’clock this morning merrymakers were wending their way home, enlivening the walk with songs,” the paper reported.

“It was also noted that their invariable custom was to beat a wild tattoo on every kitchen refuse bin placed so conveniently at intervals along the streets.”

That morning, the end of war was marked in more sober fashion, with a civic service in St Peter’s Church, Bournemouth. More services were arranged across the area for the evening.

Meanwhile, Bournemouth magistrates granted applications for closing time to be extended from 10pm to 11pm that day at Winton and Moordown Buffalo Club, Winton Liberal Club and Westbourne Conservative Club.

There was music all afternoon and evening in Meyrick Park. Boscombe followed suit, with a procession from Carnarvon Crescent Gardens to King’s Park, where hundreds joined in community singing.

The evening saw 15,000 gather in Westover Road and the Pavilion forecourt to listen to the King’s broadcast to the Empire before the merriment continued.

In Poole Park, a large raft piled with tree cuttings was towed out onto the lake, where the mayor rowed out to light it.

Beacons were also lit at Constitution Hill and Hamworthy.

George VI told the Empire that "there is not one of us who has experienced this terrible war who does not realise that we shall feel its inevitable consequences long after we have forgotten our rejoicings today”.

Many would have been mindful that humanity had unleashed new and terrible weapons. At least 129,000 people had been killed at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

With Japan defeated, the scale of suffering experienced by its Allied prisoner of war began to be revealed.

Aileen Twibill spent four years in Japanese internment camps in Indonesia, including the infamous Tjideng, which housed 15,000 women and children.

From April 1944, it was ruled by Kenichi Sonei, one of the first officers executed for crimes against civilians.

“The worst thing was the tenko – the roll call – twice a day,” she told the Echo in 2005.

“Sometimes, if he felt like it, Sonei would make us stand there in the hot sun all day, old and young alike.”

Some would drop dead where they stood.

The late Jim Mariner was the first Briton to fire on Japanese forces in December 1941 and spent the rest of the war among 1,500 imprisoned Americans.

Sixty years later, he recalled for the Echo the night of August 5, 1945.

“I said ‘If there’s a God that can hear me, please let me go home. I’m getting thin and I’ve been seven years abroad and I want to go home and I want to see my dear old mum.'

“I said, ‘Please get me home but destroy these people. They’re not right to be in a civilised world.'

“The day after was my birthday, August 6, the day the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. That was the best birthday present I’ve ever had in my life.”

Jack Cresswell, father of Bournemouth historian John, was a Royal Artillery stereographer who was captured in Malaya. He was a prisoner at Fukuoka,on Kyosho Island, when the atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki barely 60 miles away, and his diary recorded the last days of the war:

“August 8: Officers beaten for refusing to sign peace appeal letter. Terrific raids today and past few days.

“August 12 : Heavy bombing near in morning. Rumours of Russians entering war. Suicides taking place.

“August 15: Afternoon. Rumours start pouring in from all quarters of ‘senso wari’ – war finished.

“August 16 : The morning day shift paraded for work but were dismissed with the malaria epidemic excuse ... the war must be over...

“August 22 : The official announcement was made by the Camp Commandant and valuables were given back the same day. Bowing to guards was dispensed with.”

A month later, was on his way home. “Arrive Nagasaki, see awful results of one atomic bomb – miles of debris. American sailors’ band on station playing 'They all go the same way home'. Coffee and doughnuts, bath and new clothes, tongue sandwiches and iced chocolate milk.”

Frederick Harris, 91, of Kinson, served on the HMS Indefatigable, one of the few ships permitted in Tokyo Bay as the Japanese surrender was signed on the USS Missouri on September 2.

“After the surrender, our aircraft were going in over the Japanese, finding these Prisoner of War camps and dropping food for them,” he said.

He wants the occasion to be properly remembered one more time. “There are not many of us left now," he added.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here