TINKER, Tailor, Soldier, Spy author John le Carré’s father, Ronnie Cornwell, was a classy con merchant who found himself doing time on more than one occasion.

But what of le Carré’s mother, Olive?

She slipped out of his life one night when le Carré – David Cornwell – was just five and his brother seven, running off with an estate agent to start a new life in East Anglia.

David was told she was dead.

And, when le Carré – whose real name is David Cornwell – tracked her down many years later, after he had grown up, she threw a verbal grenade at his grandfather, Frank Cornwell, a former mayor of Poole.

Ronnie Cornwell (her husband and David’s dad) had been jailed in 1934 for an insurance fraud.

Writing in the New Yorker magazine in 2002, le Carré said Olive told him that it was Ronnie’s father – le Carré’s highly respected grandfather Frank – “who had put Ronnie up to his first scam, had financed it, remote-controlled it, then kept his head down when Ronnie took the fall”.

Was there any evidence for this or was it a spiked jab by a woman who (a less frequent occurence in the 1930s) had left a family she’d married into?

Olive, who like le Carré and his father, Ronnie, was brought up in Poole, certainly believed she had married beneath her. After all, her brother Alec Ewart Glassey was, for two years, MP for East Dorset.

And no evidence has emerged to suggest that Ald Cornwell was anything but a beacon of respectability.

Olive Moore Glassey was orphaned when a child and brought up by her brother Alec, 25 years her senior.

Their father, the Rev William Glassey, had been a Congregational minister in Yorkshire.

Alec Glassey, too, who was born in Normanton in December 1887, spent most of his early life there, living principally in Sheffield, and marrying Mary Eleonara Longbottom in 1910.

He took up the profession of elocution and became a teacher and reciter.

When the First World War came, Glassey took a commission in the Highland Light Infantry, seeing four years’ service and being mentioned in despatches.

In the Battle of the Somme in 1916 he was “blown up and sent to England to recuperate”. Seven months later he went back to the Western Front once more and served with the 32nd Division at Nieuport on the Belgian coast.

He commanded a trench mortar battery serving at the battlefields of Passchedaele, Lange- marcke, in the Arras sector and in the last great offensive from Amiens to Landrecies, before marching to the Meuse.

Following being demobbed, in the summer of 1919 Glassey and his wife Eleonara moved to Parkstone, Poole.

After two years “touring the country on behalf of the YMCA” he settled, becoming a deacon at the Parkstone Congregational Church... and standing, unsuccessfully, as a Liberal Parliamentary candidate in 1924.

In the 1920s, too, he was at one time chairman of Poole Town FC the team which, in 1926, reached the third round of the FA Cup before finally being knocked out, 3-1, away to Everton.

According to the 2002 New Yorker article by John le Carré, it must have been around this time that the young Olive met Ronnie Cornwell.

Alec Glassey, by now a fabled local preacher, was asked to present a cup to a local football team whose centre forward was Ronnie.

As Glassey – “a vain and natty dresser with a great sense of his social importance” – moved along the line shaking hands, Olive (like her brother, “thin and bony”) trailed behind him, pinning on their badges,” le Carré wrote.

“As she pinned one on Ronnie’s, he fell dramatically to his knees, complaining she had pierced him to the heart.”

Alec, “who on all known evidence,” wrote le Carré, “was a pompous arse, loftily condoned the horseplay”.

And Ronnie subsequently sweet-talked Alec into allowing him to call at their home – at the Homestead, 22, Penn Hill Avenue – ostensibly to woo a maid but with his sneaky eye really fixed on Olive By 1929 Ronnie and Olive had married and Alec Glassey’s own life was to change.

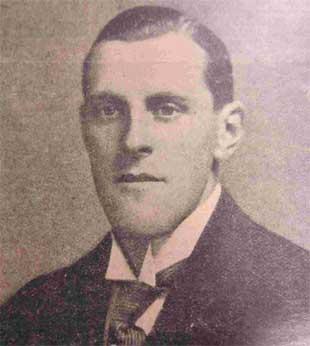

Having been chosen again as a candidate by the Liberal party to fight East Dorset in the 1929 General Election – the first after all women had the vote – Glassey narrowly triumphed and was returned as MP.

Polling 17,810 votes, he beat the Conservative GR Calne Hall with a majority of 277.

As well as being one of the tallest MPs in the Commons and, according to one national journal, “one of the most popular”, he was appointed to the role of English Whip and then, in September 1931, made a Junior Lord of the Treasury.

His Commons career, however, did not last long. The economic crisis that year led to another election being called.

In that 1931 election Glassey fought under the banner of the National Government – a coalition – increasing his vote but losing to his old Tory rival Hall Calne.

After his Commons career ended, Glassey remained very active in the Congregational Union and, for 20 years up to 1962 was a Poole magistrate – also becoming deputy chairman before retiring at 75.

“All those people who stand before us are not wicked people but weak people and the helping hand is perhaps more valuable to them than the hand ready to turn the key of the cell door,” said Glassey, who also keenly supported the NSPCC.

Blindness overtook him in 1964 and he died, aged 82, at his Penn Hill Avenue home, on June 26 1970, leaving £19,868 gross. His widow, Eleonara, passed away six years later, leaving a sum of £97,643 gross.

And what of Olive, John le Carré’s mother?

She died in the early 1980s, a few years after her former husband Ronnie Cornwell passed away in 1975.

And that dig that Olive made to John le Carré about the integrity of his grandfather, her father-in-law, Alderman A E Frank Cornwell of Poole?

She may have had good reasons to leave her husband but nothing has emerged to substantiate her remark that her father-in-law was “bent”.

He was born in Bridgwater, Somerset around 1877 and spent his early years in London. Le Carré believes he was originally a tiler.

AEF (Frank) Cornwell was certainly in Poole in 1922, for that year he was elected to the council to represent Courthill and Penn Hill wards.

A well-known local businessman – he was managing director of Messrs Ranson and Whitehead motor engineers of Boscombe and the senior partner of F Cornwell and Sons insurance brokers – he became Sheriff of Poole in 1927, Mayor in 1928 and he was Deputy Mayor in 1930.

Ald Cornwell and his wife, Elizabeth, who spoke with an Irish lilt, lived at 95 Bournemouth Road, a short distance from number 149 where Alfred Joseph Cornwell – presumably le Carré’s great grandfather –lived.

Frank then moved to 5 Mount Road, Parkstone around 1929. (Alfred Jos- eph and his wife also moved next door to number 3. He died in the summer of 1936, aged 83.) The Alderman served on the Board of Guardians, did “much useful work” as superintendent of the York Road Mission (York Road’s now Ebor Road) and was a preacher for both the Baptist and Congreg-ational denominations.

An original member of the Parkstone and Branksome Chamber of Commerce, Frank Corn- well was also a Freemason who had been Worshipful Master of the Dunkerley and Amity Lodges.

Frank and his wife later moved to St Peter’s Road, Parkstone, before he died suddenly at the age of 69, in May 1946. His funeral took place at Longfleet Baptist Church, conducted by the Rev WG Brown, the Pastor of Parkstone Baptist Church. He left a wife, three daughters and a son, Ronnie.

What was Ald Frank Cornwell like? Twelve years ago Jean Tucker, who lived in Alcester Road, Parkstone, wrote to the Echo recalling Mr Cornwell, the preacher at York Road Mission Hall where, as a child she used to go to Sunday school. She recalled charabanc outings to Lytchett or Corfe Mullen or, if it rained, tea parties in the mission hall.

“Mr Cornwell would call us outside, armed with a big jar of boiled sweets,” she wrote.

“He’d take a handful at a time and throw them down York Road hill and we had to run and pick them up – ‘scramble’ he called it – and those who had most sweets had most dirt and grass stuck on them as they were unwrapped in those days.”

And Mrs Audrey Fabb, who lived in Southern Avenue, West Moors also wrote to the Echo 12 years ago. Her cousin married one of John le Carré’s aunts.

Recalling the Alderman;’s wife, she wrote: “ Old Mrs Corne well was very friendly with my grandmother who helped to deliver some of the Cornwell children. “Many is the time that old Mr Cornwell, who was then Mayor of Poole, used to take my mother, brother and me up to London as he had business there and we would go along for the ride.”

Whatever Olive said to le Carré about her father-in-law, the question is: with no evidence at all, does Ald Corn- well really sound like a man who would take anyone for a more unscrupulous type of ride?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here