THIS month is the anniversary of victory in the Falklands War. And for the veterans it may take only a moment to be transported back to 1982.

At the time few people thought the Argentinean invasion on April 2 would lead to war.

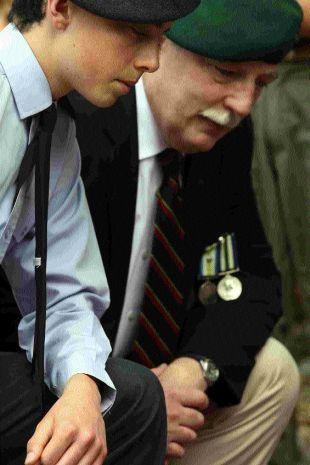

Royal Marine Bill McAlester, 51, from Burton, and his colleagues thought it would be resolved before the task force made the long journey south.

But his unit was certain about one thing. “It had been an assault on us,” he said.

“The Royal Marines garrison had been attacked during the invasion. The feeling was, ‘Now we are coming to get you back’.”

It was not until the May 3 sinking of the Argentinean cruiser Belgrano with the loss of 400 lives, and the destruction of the HMS Sheffield the next day by an Exocet missile, that war become real.

“We could see Sheffield burning about 20 miles away,” said Steve Overall, 52, from Broadstone, then a leading seaman on the HMS Coventry.

“For about three days afterwards hardly anyone spoke.”

After the landings on May 21 Steve Overall’s ship was deliberately positioned to draw air attacks. It had three confirmed aircraft kills when it was sunk by three bombs on May 25, with the deaths of 19 crewmen.

“We were all in the ops room and we heard ‘Aircraft closing’,” he said. “We fired a missile and then engaged with the 4.5 inch gun. The aircraft was still closing and we engaged with small arms.

“It all went quiet. All the lights went out. And there was a crump followed by a big flash of light.”

He suffered first and second degree burns to his hands and face that took months to heal.

The ground war began in earnest with the May 28 battle for Goose Green and Darwin and the loss of 17 members of the Parachute Regiment.

However, SBS men from Poole had been gathering intelligence on the islands for weeks in secret observation posts.

On May 21 the frigate HMS Ardent was sunk, and the casualties included 18-year-old Stephen Ford from Parkstone.

Other casualties included Kenneth Francis, from Lyndhurst, killed when a helicopter was shot down, and Welsh Guardsman Christopher Thomas, 22, from Poole, who died of shrapnel wounds.

Certain images, smells or sounds are burned in the memories of men who lived through these battles.

One of Bill McAlester’s colleagues stood on a mine.

“I will take to my grave the scream of the guy behind him,” said Mr McAlester. “He thought he had been flash-blinded.

“The guy who stood on the mine couldn’t understand why he couldn’t help the guy who was screaming. It was because he’d lost his foot.”

Leo Thornley, 64, from Bransgore, was in the catering corps aboard the RFA Sir Galahad when it was bombed and burned out on June 8, producing some of the most horrific images of the war.

He said: “I just heard over the tannoy: ‘Red alert, Red..’ then BANG.”

Amid the toxic smoke in the ship’s galley, he tried to help people, blindly grabbing the arms and legs of men who could be dead or living. He was one of the last men off, climbing down a scramble net with a man lashed to his back who had two dislocated shoulders.

“The people with burns initially just looked very light and pale,” he said. “That’s because their skin had melted off and was hanging down off them.”

Also aboard was Dave Leeming, 68, from Christchurch, a captain in 16 Field Ambulance who then treated the wounded.

He said: “The Chinese crewmen had nylon overalls that melted into the skin. I can still smell the burns today.”

British troops captured six hills around Port Stanley between the nights of June 11 and 13, losing from two to 23 men killed in each battle.

Royal Marines all had part of their training in Poole at that time, and they played a key part in this final push.

Commando David Stewart, the son of a rector from Langton Matravers, won the Military Cross during the assault on Two Sisters.

HMS Alacrity, commanded by Christopher Craig from Parkstone, fired more than 500 shells in support on the ground troops.

The garrison surrendered on June 14 and the sight of Argentina’s poorly equipped conscripts brought some sympathy from the elite British forces that had beaten them.

But the war did not finish that day for the men who had achieved this victory.

Bill McAlester said: “I don’t expect anyone to understand, but my friends died and I lived. That is a guilt complex that nobody should have to live with.”

Veterans find talking about their experiences difficult but often helpful.

The recent founding of the Christchurch and District branch of the veterans association SAMA 82, which meets on the second Wednesday of every month, is perhaps a sign of how when military men get older they seem more inclined to engage with ghosts of the past.

Leo Thornley said you can talk about these things in the military community, with people who understand what they have been through.

“It’s something you can never forget,” he added. “And you can never forget your mates.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel