WHO, when gazing out of a train window between Bournemouth to Brockenhurst, spares a thought for the navvies who built the line?

But this feat of remarkable engineering came with a grim sacrifice in terms of lost lives and limbs.

The human tale of the building of the direct railway line to Bournemouth is told in Hordle author Jude James’s new book, Treacle Mines, Tragedies and Triumphs: The Building of the Bournemouth Direct Line 1883-88 (Natula Publications £14.95).

At least 10 navvies lost their lives, the author reveals.

The story begins long before the 1880s. Southampton had been connected to Waterloo since 1840.

Subsequently a line called Castleman’s Corkscrew was built via Holmesley, Ringwood and Wimborne, extending the service to Dorchester.

A branch line was built in the 1860s from Ringwood to serve Christchurch, later extended to Bournemouth East. And another , in 1870s, from south of Wimborne to serve Broadstone and Hamworthy, the latter extended to Bournemouth West.

But there was no direct line to Bournemouth for another decade.

Eventually work to rectify this was launched in the 1880s, linking Lymington Junction with Christchurch,.

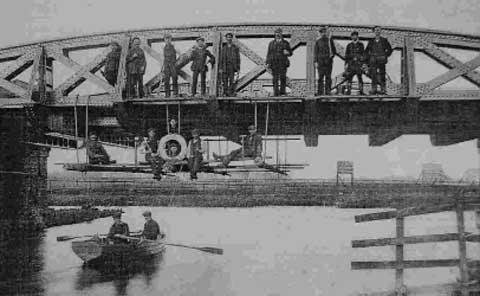

Itinerant navvies arrived to provide the toil, joined by local labourers, attracted by the pay of 3/- or 4/- a day (15p-20p) from the farms where agricultural depression was biting.

Jude James’s account tells how the original contractor went into liquidation and of other major problems such as the cutting the Sway bank where the workmen were forced to deal with terrible gooey clay.

The navvies would return home to the cottages where they lodged, or to the hutlets built to accommodate them, looking as if they had “been wallowing in treacle”, giving rise to the origin of the ‘Sway treacle mines’ term that endured into the mid 20th century.

But what makes this account fascinating are the tragic stories of individual navvies.

John Clark, for example, was driving a horse-drawn tip-cart when he tripped and fell across the rails and his arm was crushed.

His limb was amputated and he died soon after.

“His funeral took place in Sway churchyard on May 3 1885... before what was described as a large solemn gathering of his fellow workmen,” writes the author.

Life came cheaper in those dangerous days – the medical officer of the time reported that the local death rate increased from 14.75 to 18.5 per thousand largely due to overcrowding in the labourers’ badly-ventilated cottages. But respect for the dead was important.

A 23-year-old man called John Biddulph slipped and fell whilst at working at a cutting and the inquest heard a number of wagons passed over him killing him instantly.

And 36-year old Alfred Whitcher from Bashley became trapped beneath a collapse of material when working on the cutting at Newhooks near Sway.

He was dead by the time his colleagues got him out. Lucy, his widow and mother of his children, was awarded £150.

Jude James recounts how Frederick Clarke died after the ganger, Charles Young, replaced him on the brakes. Clarke was jolted off the buffers and killed on the spot.

His headstone survives in Sway churchyard.

Charles Young himself was killed in Sway the following year, aged 49, after an accident at Sway station.

He had hitched a lift home for his midday break on an engine’s footplate but tripped as he jumped off.

Young, bleeding from both legs, called to a fellow navvy: “Oh Charley, I’m a dead man – go and fetch the missus!”.

He died at home that day.

James Jude’s book tells of the agonies endured by navvies and of the crimes some committed in the feat of building the railway that included stations at Sway, Milton and Hinton Admiral.

The line was finally opened with great ceremony on March 5 1888, connecting Waterloo to Bournemouth at last.

Distinguished passengers arrived on the inaugural train at Bournemouth East station on Holdenhurst Road , that was decorated with flags and streamers.

They lunched well on everything from turtle soup and lobsters to roast turkeys’ tongues and speeches were given about the importance of the connection that would prove to be a catalyst to the seaside resort’s growth.

They paid tribute, too, to the role of the contractors.

But, says Mr James, “nowhere can be found a reference to the men who built the line or the sacrifices a number of them made during the great work.”ordle author Jude James new book, Treacle Mines, Tragedies and Triumphs

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here