AN elderly man snores with a raspy purr, air-conditioning sighs contentedly and chopsticks clatter in plastic tray compartments laden with glutinous rice, fragrant winter melon and tender beef and mushroom, as a scroll of orange LED dots above the doorway of the 16th carriage relays our current speed: 351 km per hour.

I quietly drink in the soothing soundtrack to the world's fastest bullet train between Beijing South and Shanghai Hongqiao stations. No cacophonous clatter of wheels over rail joints, jolted gasps caused by sudden tilts in the track or fizzing frustration from overcrowded carriages. Just a four hour and 28-minute symphony of dreamily reclined calm, composed by impeccable Chinese engineering.

Serenity threatens to derail just once, during passport checks and luggage scans at the station. Flammable liquids are unwelcome passengers on China's sleek-nosed high-speed trains, so toiletry bags are hurriedly divested of aerosol antiperspirants, hairsprays and insect repellent by stony-faced security guards.

The 1,318km journey down the eastern coast is the centrepiece of the opening two legs of Rail Discoveries' 13-day escorted group tour of China, which concludes with a four-day scenic cruise along the Yangtze River and visits to the Panda Research Centre in Chengdu and Emperor Qinshihuang's Mausoleum Site Museum in Xi'an, guarded by life-size pottery soldiers, horses and chariots of the Terracotta Army.

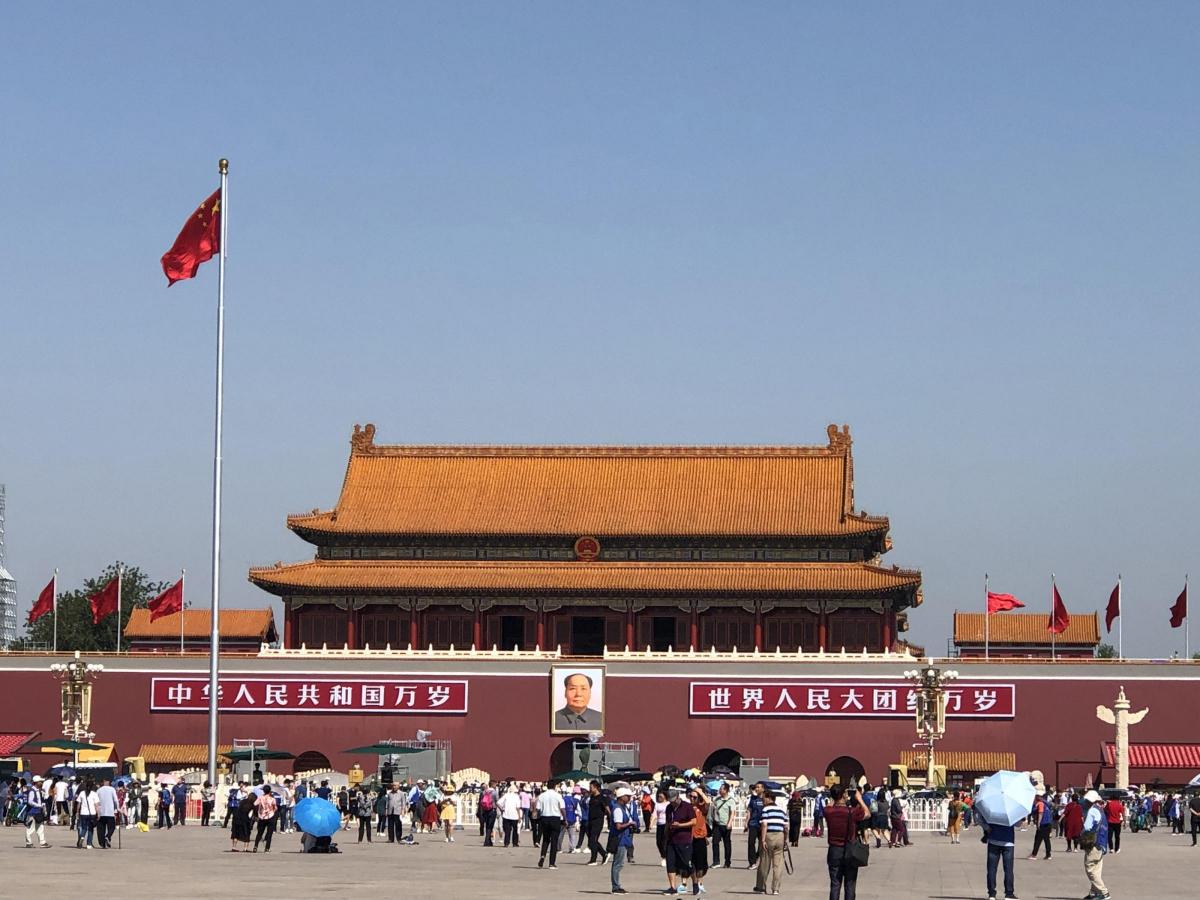

The termini of Beijing and Shanghai epitomise the intriguing contradictions of modern China; centuries of dynastic rule and imperial tradition coupled to the future-facing, technologically-driven ambition of the second-largest economy in the world. A manufacturing powerhouse founded on Mao Zedong's pillars of equality, mutual benefit and respect in October 1949, cloaked behind a great firewall monitored by the ruling Communist Party.

Predictably, passports are carefully checked against names on pre-booked tickets to the Forbidden City. It has been 95 years since Puyi, the last ruler of the Qing dynasty, was expelled from the palace.

The intriguing and sobering reality of China's inner conflict crystallises during a rickshaw ride to the Beiguanfang Hutong of traditional courtyard residences dating back to the Yuan dynasty in the late 13th century.

Ornate courtyard gates, which face south-east to counter biting winter winds from the north-west, are adorned with hexagonal blue knobs to reflect an owner's social standing.

These neighbourhoods, threaded with narrow grey-bricked alleyways, huddle on some of the most expensive land in Beijing. Ironically, they are home to some of the poorest families. Residences are often served by communal toilets and pass down generations to protect a way of life.

Newly constructed totems of glass and steel pale next to the undulating granite serpent of the Great Wall. The 2.5km Mutianyu section is a 90-minute drive north of the capital and opened in April 1988 after five years of renovation.

Orange cable car gondolas seating up to six people take four nerve-racking minutes to pendulously ascend 640 metres to one of the wall's majestic watchtowers.

Staring through a knee-high loophole on the crenellated battlements, where archers once targeted invaders, I feel humbled to be standing atop centuries of back-breaking endeavour designed to repel foreigners, like me.

When the bullet train pulls into Shanghai Hongqiao station and disgorges passengers with proud punctuality, there is a palpable change in mood from the capital. Swarms of fashionably-dressed students and twentysomethings kindle a cosmopolitan, laid-back vibe, enforced by the reduced visibility of police and military personnel.

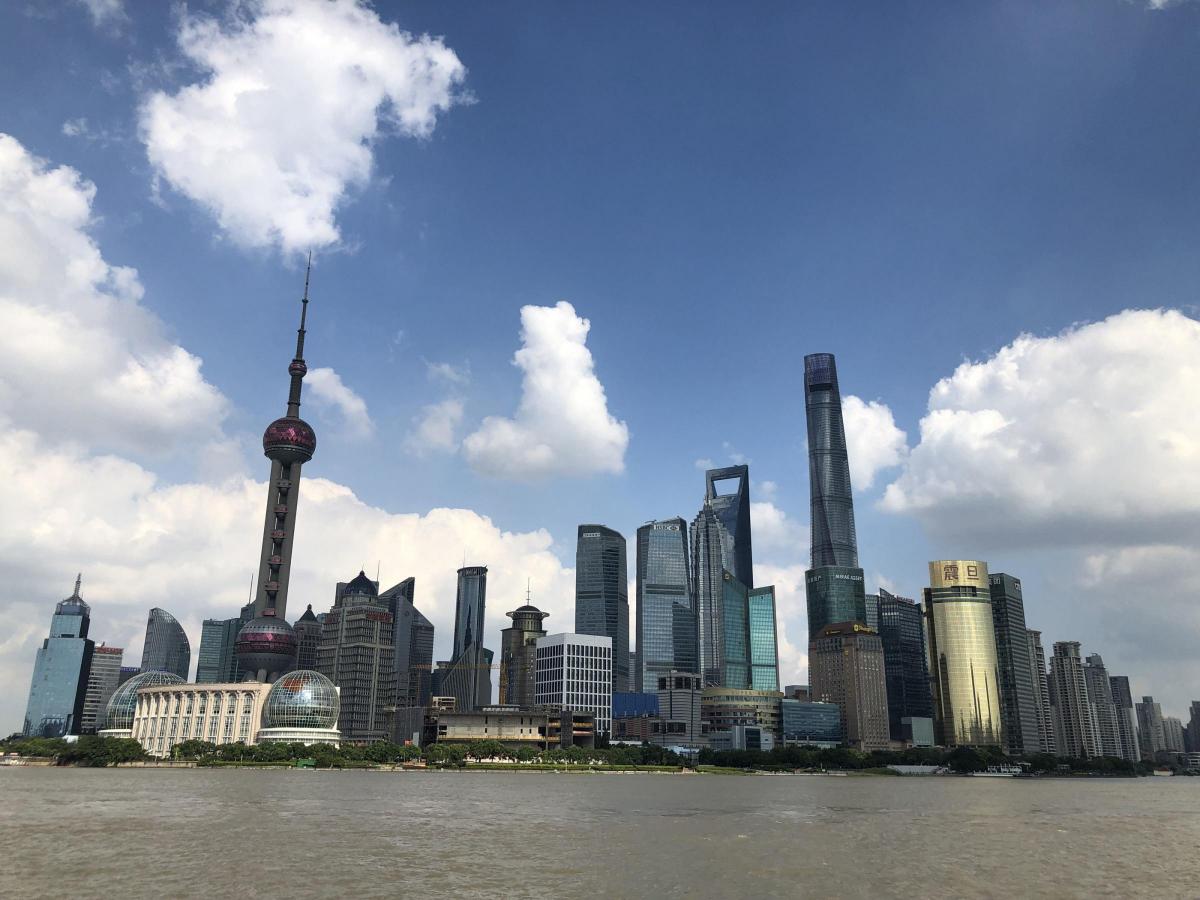

A 60-minute drive into the city centre during rush hour is framed by a futuristic sprawl of playful architectural follies. The bottle-opener shaped 101-storey Shanghai World Financial Center, the flat heel and pointed toe of the boot-like L'Avenue office building, LED-lit spheres skewered on needles of the Oriental Pearl TV Tower and the British-designed Bund Finance Center cloaked in three moving curtains of downward-facing copper organ pipes.

The city's colonial legacy is reflected in the formal splendour of the mile-long Bund waterfront promenade. On this 'Oriental Wall Street', the Shanghai Pudong Development Bank spares no expense with an octagonal entrance hall dominated by columns of Italian marble and a restored ceiling mosaic, depicting signs of the Zodiac.

After the razzle dazzle of nocturnal Shanghai, serenity dawns in the Yu Garden in one of the older quarters of the city. Once a private oasis of the Pan family, the restored classical Chinese garden boasts five acres of pavilions, halls and shimmering pools festooned with brightly-coloured Koi and playful turtles.

My bubble of serenity is eventually burst by the jostle of the adjacent Yuyuan Bazaar, with a picture-perfect floating tea house and a bewildering array of bite-size morsels, including crispy fried cakes embedded with Chinese chives (£1.50) and baskets laden with pork and crab meat-filled xiaolongbao soup buns (£4 for six).

Supersized servings of the dumplings (£4 each) demand extreme caution and a straw to carefully slurp out scalding hot salty broth, before devouring the deflated dough case and filling. Despite some occasional acidity, my appetite for the delicate flavours of modern China stays firmly on track.

How to plan your trip

Rail Discoveries (raildiscoveries.com; 01904 734 812) offers a 13-day Discover China escorted group tour from £2,095 per person. Price includes scheduled flights from London Heathrow, all rail and coach travel, hotel accommodation, Yangtze River cruise, sightseeing tours and excursions, breakfast every day and selected lunches and evening meals. British citizens are responsible for securing a valid visa, which costs £151 per person. For more information, visit (chinese-embassy.org.uk/eng/visa/).

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel