THERE were no poppies and Whitehall had no Portland stone cenotaph.

The first national act of remembrance for Britain’s war dead took place 99 years ago this Sunday.

An Armistice had spelled the end of fighting in the Great War on November 11, 1918, but the war had not officially ended until the signing of the Treaty of Versailles the following June.

Across the nation, people responded to King George V’s call for a national tribute to those who had died for their country. Many crowded their local churches, while millions more just stopped whatever they were doing at 11am to take part in a two-minute silence.

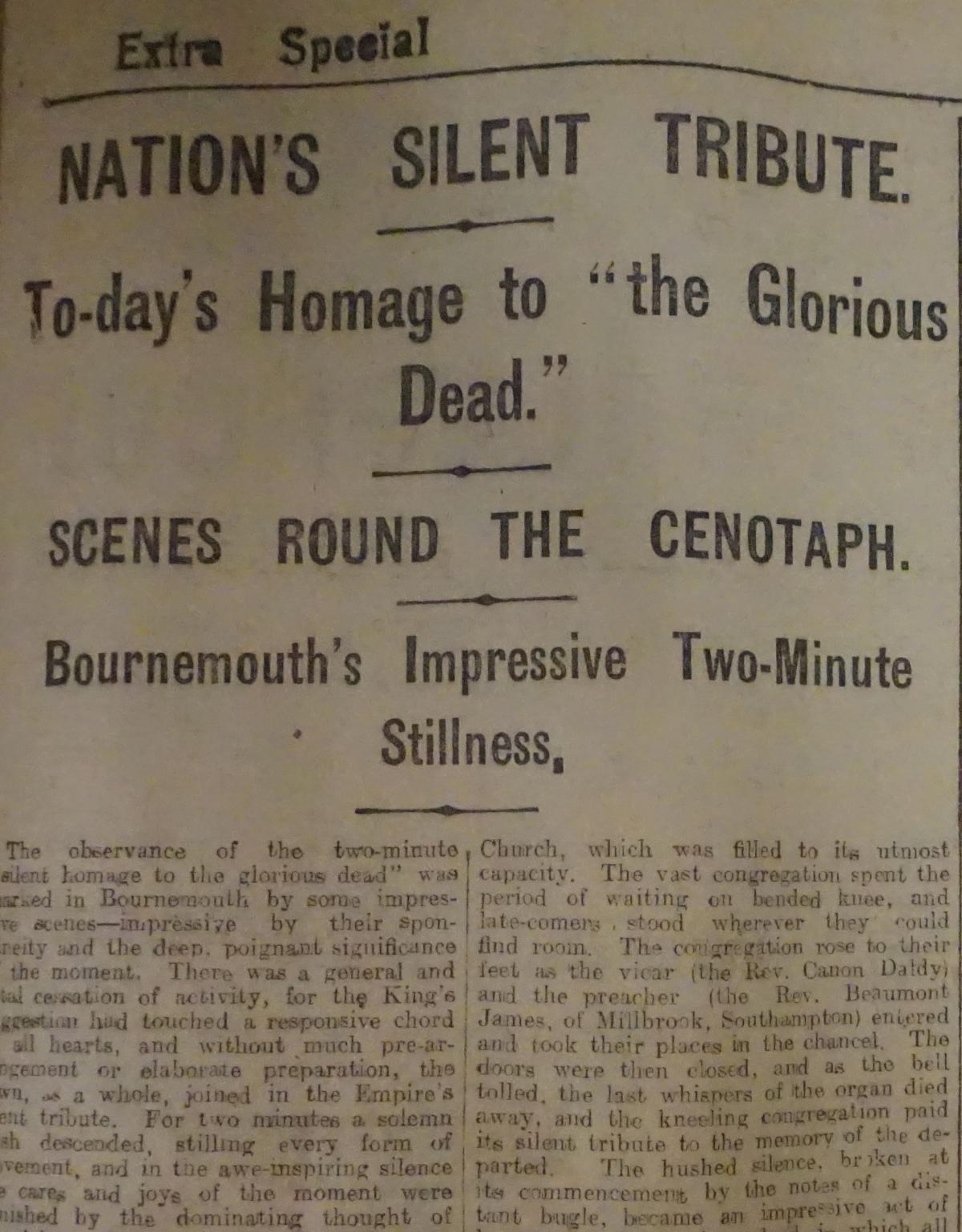

The Daily Echo of November 11, 1919, told of that morning’s events in Bournemouth and Poole.

The report began: “The observance of the two-minute ‘silent homage to the glorious dead’ was marked in Bournemouth by some impressive scenes – impressive by their spontaneity and the deep, poignant significance of the moment.”

“There was a general and total cessation of activity, for the King’s suggestion had touched a responsive chord in all hearts, and without much pre-arrangement or elaborate preparation, the town, as a whole joined in the Empire’s silent tribute.”

At 11am sharp, Bournemouth town centre went suddenly silent and the trams came to a halt, as the power to the network was switched off.

Flags on buildings were lowered to half-mast. Cars and commercial traffic came to a stop. Staff in the town’s businesses lined balconies or stood outside shops.

There were around a dozen char-a-bancs laden with passengers for a morning drive, the Echo reported. All the occupants rose, the men removed their hats and the women bowed as if in prayer.

“On the last stroke of the hour the silence that fell on the busy centre became complete. The assembly, numbering thousands, stood in reverential stillness, officers remained at attention, and over by the Upper Gardens entrance women knelt on the pavements in prayer,” the paper noted.

There were similar scenes at Lansdowne, as the college clock chimed 11am.

And at the town’s normally bustling Arcade, “the effect of the great silence was most marked”.

The town’s Central and West railway stations also came to a halt. In the bay, all the boats were anchored by 11am, and the men on shore stopped work and stood with hats off and heads bowed.

The town’s churches were full as people prayed and reflected.

It was a day when, as the Echo noted, Bournemouth “cast off its unemotional mask”.

The paper said: “Our phlegmatic imperviousness to sentiment and public reticence from any form of display of feeling, gave way under the pressure of the most poignant memories.”

Many were remembering where they had been a year ago when the Armistice took effect.

“Recollections of the familiar faces of pals who made the supreme sacrifice, ere that eventful hour arrived, moved them to a reverence as only such recollections can,” the Echo added.

At Whitehall, whose cenotaph was then a temporary structure, the King laid a wreath, bearing a card in his own handwriting; “In memory of the glorious dead, from the King and Queen, November 11th, 1919.”

Remembrance Day would become an institution. Whitehall’s Portland stone cenotaph was erected in 1920 and the first Poppy Appeal was held in 1921 – with poppies initially made by women and children in devastated areas of France, before ex-servicemen with disabilities took over in 1922.

There were no Remembrance Day events during the Second World War, but the tradition resumed in 1945.

The acts of remembrance were moved to the nearest Sunday to November 11, but in the 1990s, the idea of a two-minute silence on the day itself was revived.

By 2009, there were no World War One veterans left to join the commemorations.

But whether in Korea, the Falklands, Afghanistan, Iraq, and the troubles of Northern Ireland, there have continued to be service personnel whose ultimate sacrifice deserves remembrance.

* The Daily Echo and sister papers across the south are marking 100 years since the end of the Great War with a 96-page commemorative publication. It tells the story of people involved at home and on the battlefront.

It costs just £1.50 and has a limited print run. It is available by visiting bournemouthecho.co.uk, calling 0800 731 4900, or from a host of local stockists.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel