IT could have been a master stroke, shortening World War Two by months in Europe.

As it turned out, Operation Market Garden was a costly sacrifice of lives, and its failure meant the conquest of Germany would be slow and hard.

Dorset and Hampshire regiments played a crucial role in the ill-fated operation, which was conceived by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery in the summer of 1944.

Montgomery persuaded General Dwight Eisenhower, supreme commander of the Allied forces in Europe, to back his plan.

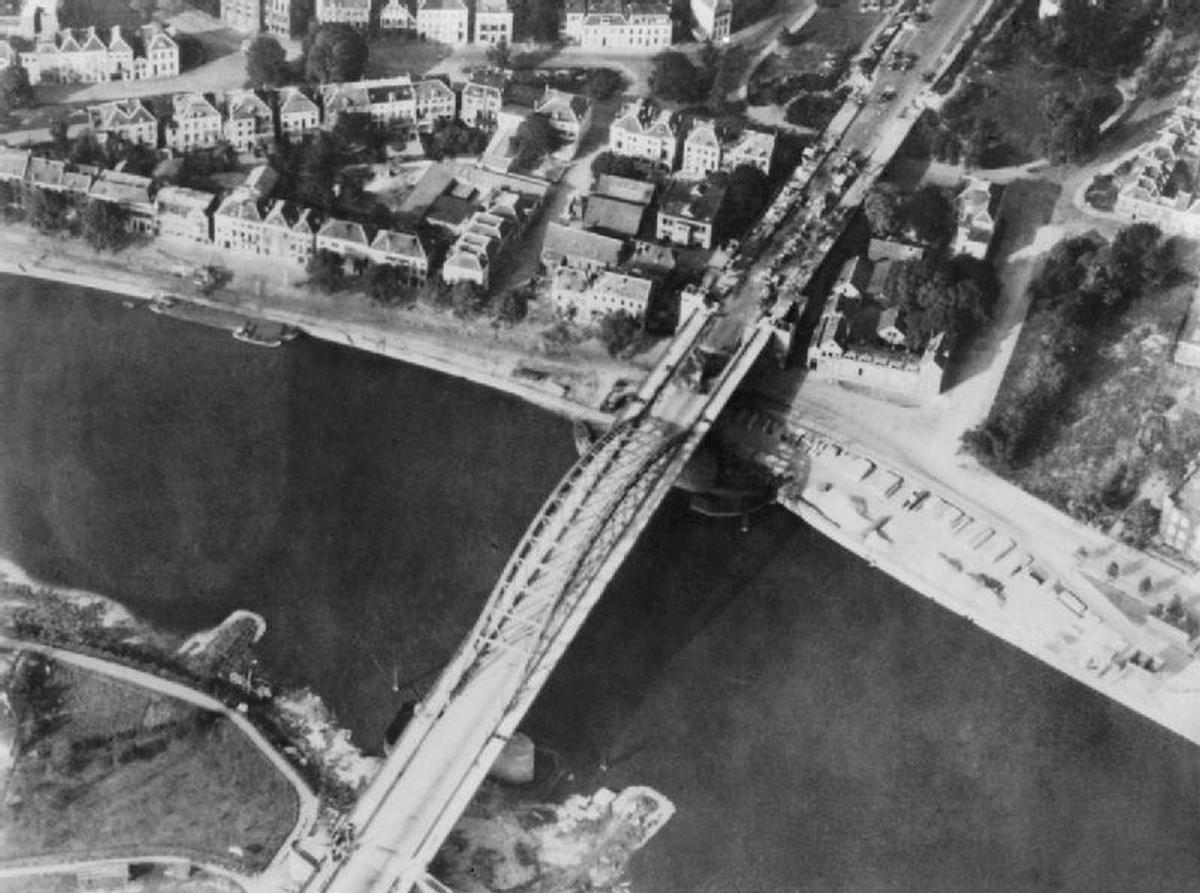

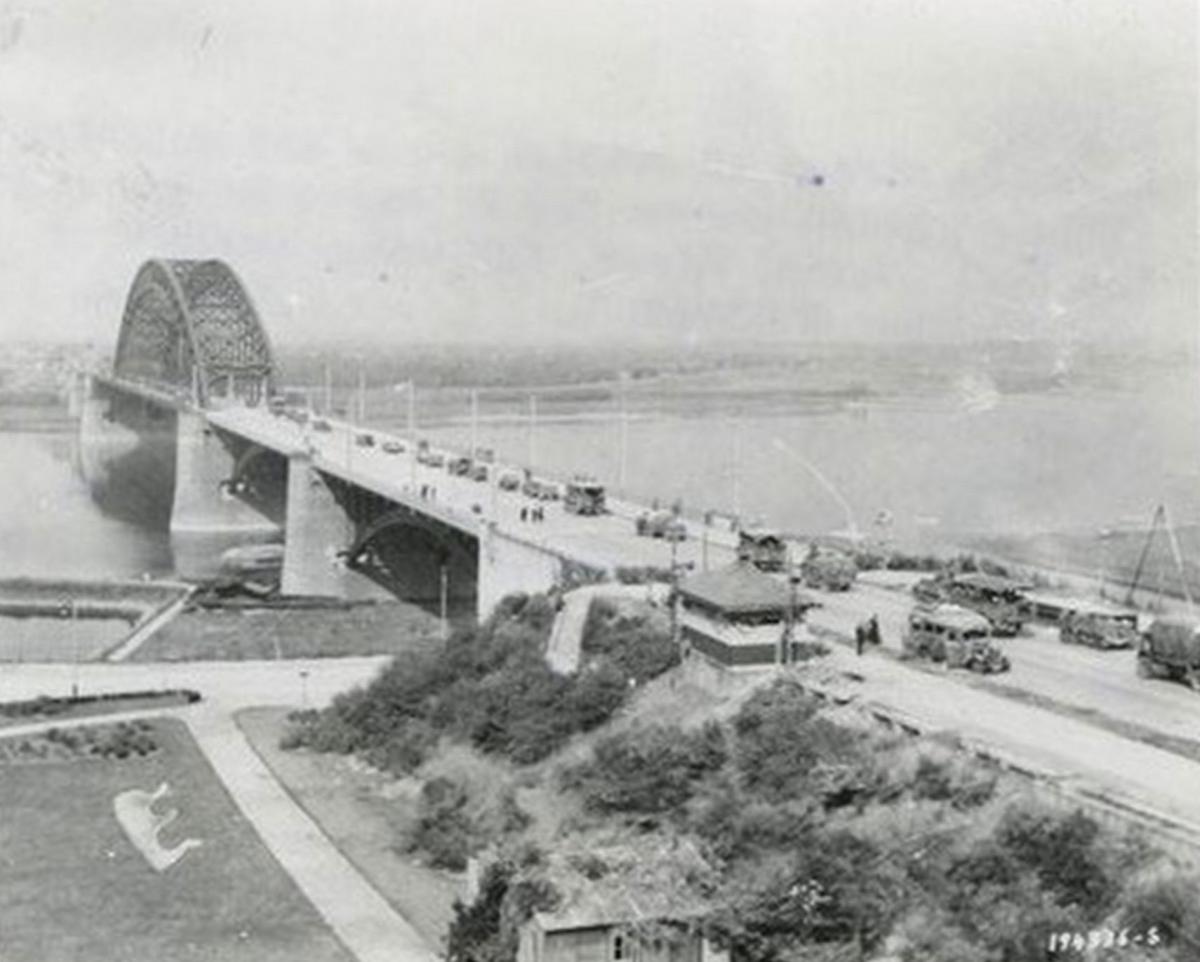

The idea was to drop thousands of paratroopers behind enemy lines in the Netherlands, to hold onto key road and rail bridges until Allied tanks could relieve them.

Had it worked, the Netherlands would have been liberated and the Allies would have a route round Germany’s Siegfried Line defences. They could have driven into Germany’s industrial heartland, and it might have been the western Allies who reached Berlin first, rather than the Russians.

The operation began on September 17, when airborne divisions began landing by parachute and glider, and all the target bridges were eventually captured. But the plan quickly ran into trouble.

The 10,000 British and Polish parachutists who landed at Arnhem were seven miles from its bridge, and only one battalion reached its objectives.

With the British 30 Corps unable to reach Arnhem before German forces overwhelmed the paratroopers, the operation turned into a bloodbath.

On September 24, the Allied crossing of the Rhine was abandoned, and the objective became the defence of a new front line in Nijmegen.

The 43rd Wessex Division was sent to support the Guards Armoured Division in its drive to relieve the airborne forces at Arnhem.

By the time the Dorset Regiment crossed Nijmegen bridge, the airborne forces at Arnhem had been overwhelmed. Despite this, the 4th and 5th battalions of the Dorset managed to force their way up the south bank of the Rhine west of Arnhem.

When plans to hold the bridges were abandoned, the Dorsets were ordered to cross the river to relieve their airborne comrades. Of the 315 who reached the north bank, only 75 returned.

The 4th Battalion became the only non-airborne unit to win the Airborne Pennant for the Arnhem campaign.

The 5th Dorsets, meanwhile, took to the water to ferry the airborne survivors back to the south bank.

Among the many who told their stories of Arnhem later was Henry Cluett, from Hamworthy, who died in 2009. He was a front gunner and driver with the Coldstream Guards.

He remembered the crash-landed gliders which had delivered troops to the battle zone.

“I climbed up into one glider and found a bullet-proof vest full of bullet hole,” he said.

“I wore it for two or three days but began to feel ashamed of myself for having protection my colleagues didn’t have, so I took it off.”

He was escorting some prisoners when a shell landed in front of them, sending a piece of shrapnel through his clothes and into his makeshift cigarette case.

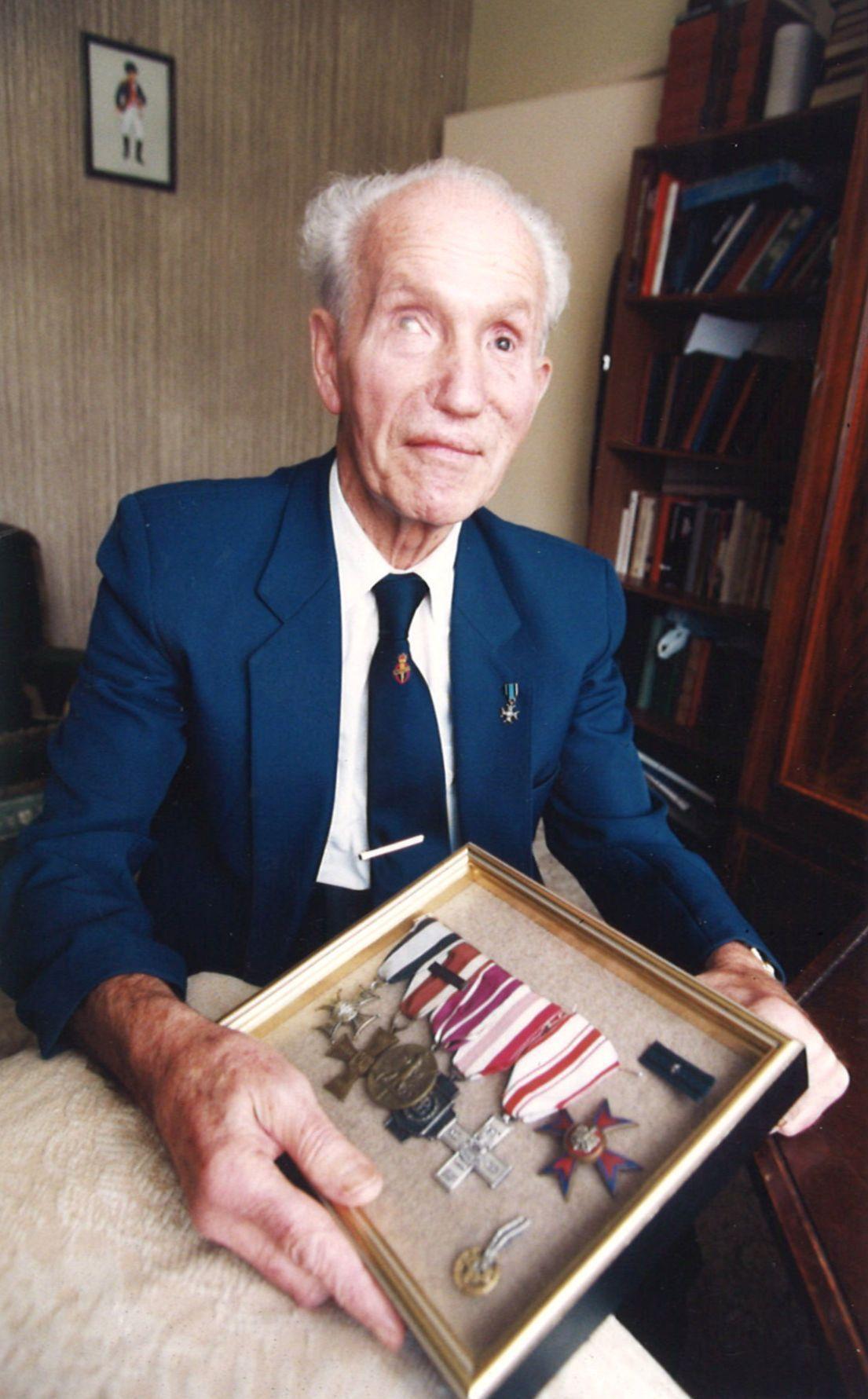

Sgt Major Laurie Symes was with the 7th Hampshire Regiment’s D Company.

It took five days for the regiment to reach Nijmegen. But the British 1st Airborne Division was in tatters buy then and the British XXX Corps could not break through.

For four days, the Royal Hampshires attacked a factory which was occupied by the SS and full of machine gun nests.

On October 4, Sgt Major Symes and the 131 men of D Company launched a dawn raid on the factory in thick mist.

Sgt Major Symes’s 26-year-old best friend, Captain Hank Anaka, picked up a machine gun and charged an enemy strongpoint, but was gunned down.

At his Christchurch home in 2005, Mr Symes recalled: “The terror is waiting to go into battle, that’s when you’re frightened. All sorts of things go through your head. You worry whether you are going to let down your men or yourself.”

In later life, Mr Symes became national chairman of the Market Garden Veterans’ Association. He made an annual pilgrimage to the cemetery in Holland where his friend was buried, until his own death in 2012 at the age of 92.

In 1977, the Arnhem mission was dramatised in Richard Attenborough’s film A Bridge Too Far. Among the all-star cast was Gene Hackman as General Stanislaw Sosabowski, the independent Polish commander who questioned Montgomery’s plan.

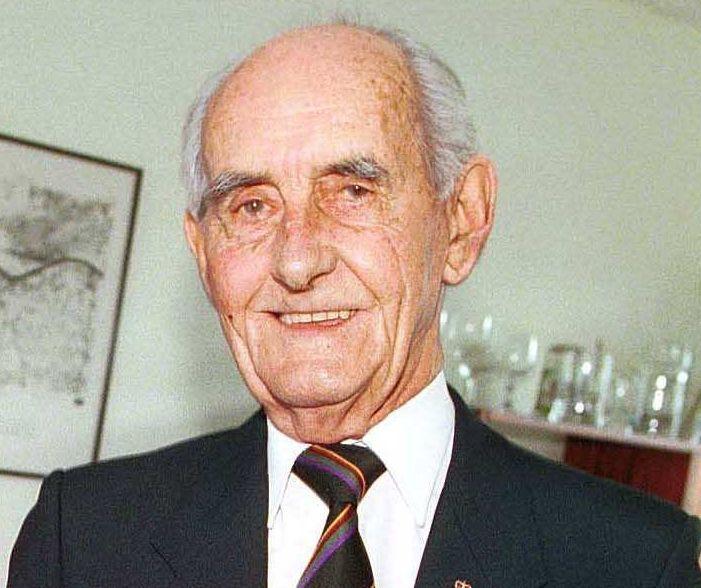

On September 21, 1944, when the fight for Arnhem was already lost, Sosabowski had to lead the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade into battle, even though the Germans were waiting at the drop zones with machine guns.

The general’s son Stanley later became a GP and retired to Wimborne.

Speaking many years later, he explained how his father was forced to take part in a plan he doubted.

Stanley, who was blinded after being shot in the face during the Warsaw Uprising,

He said: “My life is not important. But my father, he was a hero.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel