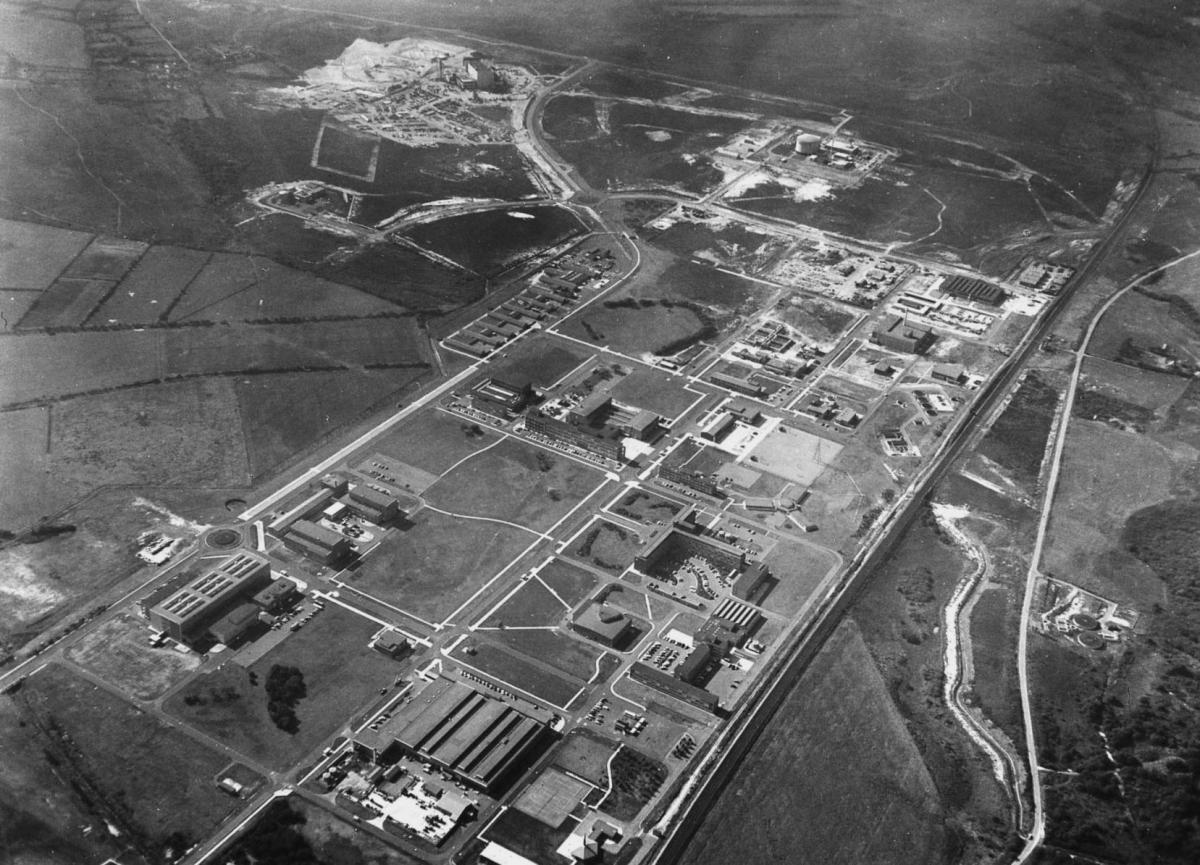

FOR several decades, a part of rural Dorset employed thousands of people in the service of cutting-edge developments in nuclear power.

A new chapter in the history of the former Atomic Energy Establishment (AEE) site at Winfrith began last week, when George Osborne announced the formation of an Enterprise Zone there.

Meanwhile, a new book – Remembering AEE Wifnrith: A Technological Moment in Time – recounts the history of the site which, at its peak in 1966, had 2,350 staff.

The author is Peter Fry, whose father Donald was the first director of AEE Winfrith.

Peter Fry says Winfrith belongs to a “golden age” of British science.

In a foreword, Alan Neal, a former head of site there, says: “Almost any problem I had, I could find an expert, often a world-class expert, on my doorstep, who would be willing to freely give his or her time to help me.”

The Winfrith story begins in 1954, when the newly established United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) was looking for a site to supplement its first atomic energy research establishment, Harwell in Oxfordshire.

The purpose of the Winfrith plant would be to develop experimental reactors which could later be built full-size.

But the proposal received a frosty reception from landowner Colonel Joseph Weld, and from a specially formed opposition group, the Dorset Land Resources Committee.

The government passed the Winfrith Heath Bill in 1957, effectively giving UKAEA permission to acquire the land and begin work. UKAEA acquired 650 acres by compulsory purchase order and

gained the use of other land, taking the site to 1,350 acres.

Early construction involved building a concrete reservoir under Blacknoll Hill with the capacity to hold 1m gallons of water.

Then there was the Arish Mell Pipeline –parallel pipes which ran for more than five miles under the ground to the shore at Arish Mell. The 'active' pipes then ran two nautical miles out to sea.

To house its workforce, UKAEA bought 153 homes in Bournemouth and Poole for staff to rent, as well as 127 in Weymouth, 100 in Dorchester, 24 in Wareham and 12 in Wool. The Durley Hall Hotel at Branksome Chine was bought in 1958 for single staff and temporary accommodation.

Winfrith officially opened on September 16, 1960. The first major building to become operational was the Apprentices’ Training School, which trained young people from across the UKAEA Research Group.

Their training originally included a rigorous two-and-a-half hours of gymnastics under former Marine commando Prossser James.

Apprentices stayed at Egdon Hall Hostel at Weymouth, built on a tight schedule by James Drewitt & Sons of West Howe.

Winfrith became known for two major reactor projects.

The first was the Steam Generating Heavy Water Reactor (SGHWR), whose two rows of cooling towers were a landmark on the site. It produced its first electricity on Christmas Eve 1967.

The reactor was officially opened in February 1968 in the presence of the Duke of Edinburgh and technology minister Anthony Wedgwood Benn.

The reactor produced enough power to supply a town the size of Bournemouth – and UKAEA made millions of pounds from supplying the National Grid.

SGHWR was hailed a technical success, but by 1976, the development of similar reactors was scrapped amid a changing market.

The reactor, however, continued to operate, supplying the grid for almost 23 years. Its closure in 1990 resulted in the loss of 700 jobs.

The Dragon – or High Temperature Gas-Cooled Experimental Reactor – project was an international effort, begun in 1960, involving 12 European countries at Winfrith.

It was housed in a large containment building on the west of the site, with its own ventilation sack. There were 200 professional staff on the project within two years, half of them from overseas.

The reactor was operational from 1964 and the five-year project eventually lasted 17 years. It closed in 1976, having been credited with demonstrating the system’s superiority over competing reactor types.

Winfrith was also home to eight smaller, low-power reactors: Zenith I, Zenith II, Nero, Juno, Nestor, Dimple, Zebra and Hector. These were, Mr Fry writes, effectively “large pieces of laboratory equipment” for the design of power reactors.

Many nuclear establishments were gradually run down in the 1970s, and by 1978, Winfrith’s staff numbers were down to 1,800.

With the shutting down of the SGHWR in 1990, Winfrith became more involved in developments for the processing and disposal of nuclear waste, but the centre’s days were numbered.

In 1995, the eastern part of the site became the Winfrith Technology Centre scientific and technical part, while 218 acres of the western site was decommissioned.

Dragon and SGHWR are the only remaining reactors whose decommissioning has not yet been completed.

The eastern part of the site is now the property of the Homes and Communities Agency. It learned last week that the site, now branded Dorset Green, would become an Enterprise Zone, a designation aimed at attracting cutting-edge, environmentally sustainable businesses.

That could mean Winfrith being at the cutting edge in the 21st century as it was in the 20th.

* RememberingAEE Winfrith is published by Amberley at £12.99.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel