IT was initially known as the Cheddington Mail Van Raid – but before long, it had acquired the more dramatic title of the Great Train Robbery.

In the early hours of August 8 1963, 15 men held up a mail train carrying a large quantity of cash between Glasgow and London. They got away with £2.6million in used notes.

The hunt for the gang transfixed the nation. And the first arrests were made days later in Bournemouth.

A young Detective Constable, Charlie Case, was one of the arresting officers, and still lives in Luther Road, Winton.

“It’s only in late retirement – I’m 79 now – that people have wanted to come and talk to me,” Mr Case says modestly.

“I’m one of the few that’s still current.”

Sixteen men are believed to have been involved in the plot to stop the mail train. Roger Cordrey, one of the pair arrested in Bournemouth, was a former railwayman who put a cover over a green signal light. The gang wired a battery to the red signal to bring the train to a halt.

Driver Jack Mills was beaten with an iron bar and forced to take the train 600 yards further along the track so the thieves could unload their haul. They drove 28 miles to Leatherslade Farm to divide the money.

At dawn, Detective Chief Superintendent Malcolm Fewtrell, head of Buckinghamshire CID, arrived at the crime scene.

He was later to retire to Swanage, where he died in 2005. In 2003, he told the Echo about that morning.

“It was almost comical at first,” he said.

“There were 70 postmen peering out of uncoupled carriages wondering what was going on. But the sight of Mills, a very courageous man, lying semi-conscious on the floor after being brutally coshed is one that will never leave me.”

Police found the deserted Leatherslade Farm hideout on August 13. The breakthrough in Bournemouth came the next day.

Mr Case remembers being at the station with a colleague, DC Peter Stutchbury. “CID in those days dealt with all crime. That included stolen bikes, which DC Stutchbury was dealing with, and panties stolen off the line,” he remembers.

He took the call to go out with Detective Sgt Stan Davies to see Ethel Clarke, a policeman’s widow in Tweedale Road, off Castle Lane West.

“She had put an advert in a shop window in Moordown advertising her garage for rent. These two chaps turned up and left a deposit in 10 shilling notes for six weeks,” Mr Case recalls.

“Because of her comments and suspicions, we turned up at Tweedale Road. We had a cup of tea with Mrs Clarke and while we were inside, she said ‘Oh, they’re coming back’.”

The officers asked to look inside the Austin van.

“They objected to this and, in police words, a struggle ensued,” he says. “That involved tussling with them and bringing down a lot of trellis. They were shouting that they were being attacked.

“Joe Public stood around gawping. Not many people had a telephone at home then. Eventually, the uniform lads turned up.

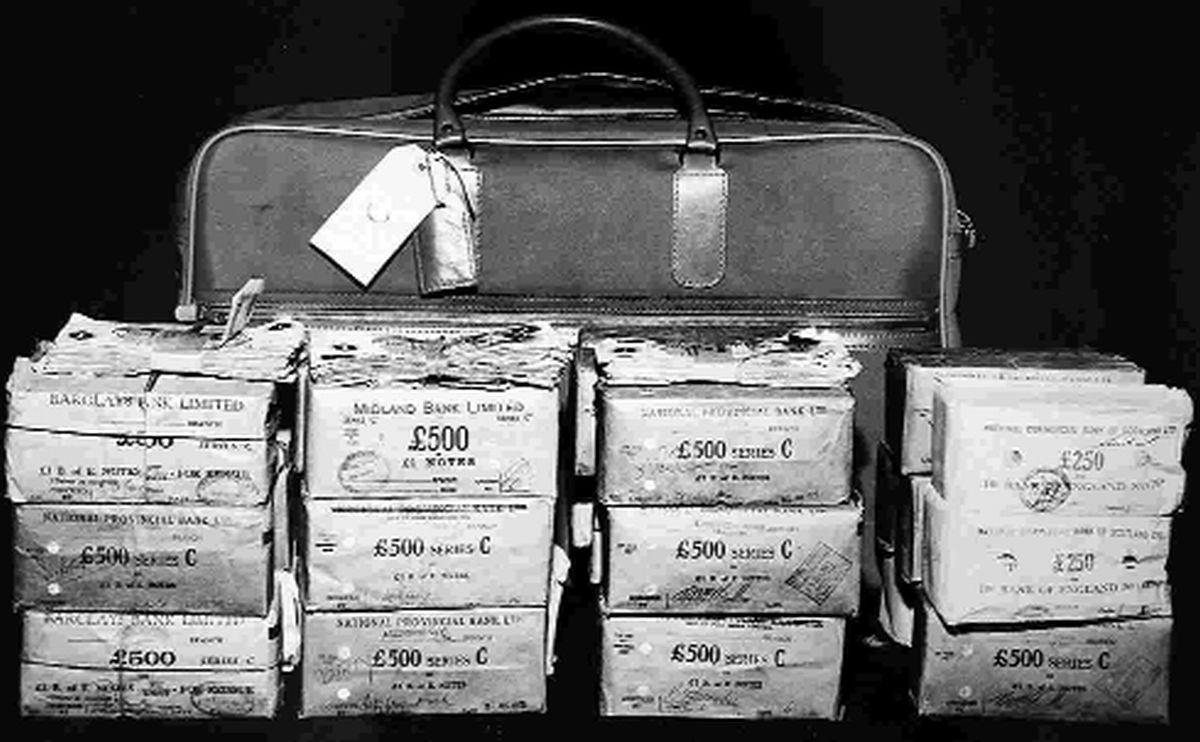

“They were detained and in the back of the vehicle were suitcases and hold-alls stuffed with bank notes, including lots of 10-bob ones.”

The two men turned out to be Roger Cordrey and William Boal, who had been living for several days in a flat above Mould’s florists in Moordown.

They were taken to Bournemouth police station, where DCS Fewtrell and his colleagues from Buckinghamshire soon arrived.

“I might as well have gone on leave for a while. It was all very high-powered,” says Mr Case.

Bank clerks were brought in to count the cash. “Forensically, I expect a lot of clues disappeared because everybody was handling it,” he adds.

Meanwhile, DC Case finally got around to eating his lunch – and had to show his sandwich box to prove he hadn’t dropped any cash into it.

After giving evidence at the trial in 1964, Mr Case enjoyed a long career with Bournemouth CID. He also manned an inshore lifeboat and taught lifesaving skills to children. After reaching retirement age, he continued with the police as a warrants officer.

As for Mrs Clarke of Tweedale Road: “Ethel Clarke had all sorts of threatening letters and phone calls,” says Mr Case.

“She in turn paid for a holiday for Jack Mills to the Channel Islands – she had picked up £15,000 in reward money.”

Heavy sentences

Most of the train robbers were caught over the coming weeks and in 1964, 11 defendants were sentenced – the heaviest sentences being 30 years.

Cordrey, who was the only robber to plead guilty and give back his share of the money, was jailed for 20 years.

Boal was jailed for 24. Their terms were reduced to 14 years each on appeal.

Boal maintained his innocence and the crime’s mastermind Bruce Reynolds said he had not heard of him. Boal died in prison in 1970 and his family have recently been campaigning to clear his name.

Cordrey was released in 1971 and went back into floristry in the West Country.

Bruce Reynolds fled to Mexico but was arrested in 1968 in Torquay and sentenced to 25 years in prison. He died earlier this year.

Ronnie Biggs, though far from the most important robber, became the most famous, largely for escaping prison and fleeing to Brazil. He returned to London in 2001 and was sent back to prison, from which he was released due to ill-health in 2009.

Malcolm Fewtrell later told the Echo that he did not blame the criminals for “cashing in” on their fame.

But he had no sympathy with the romantic accounts of the crime.

“It was a sordid crime committed for great gain. The robbers went armed, not with guns but with pick-axe handles and woe betide anyone who got in their way, as unfortunately one poor man did,” he said.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel