FOR decades it has been assumed that the home of George Loveless, the leader of the Tolpuddle Martyrs, had been demolished.

But Poole author Dr Andrew Norman is convinced that his former house in Tolpuddle still stands today.

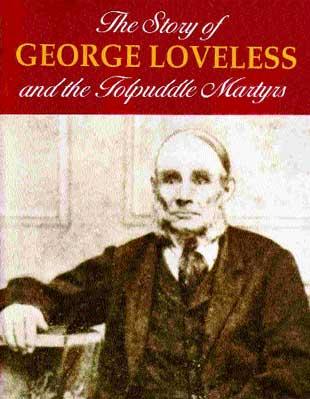

In his new book, The Story of George Loveless and the Tolpuddle Martyrs, Dr Norman explores the story of the God-fearing Methodist whose humiliation and punishment, alongside five other villagers, became a milestone in the early history of trade unionism.

In it, Norman emphasises that they were not greedy men. They were not firebrands but men “whose simple demand was to be paid a living wage at a time when, according to Loveless, their weekly wages had been cut to seven shillings (35p) from, at one time nine shillings (45p) and the employers’ intention was to lower it to six. It would be impossible to live honestly and feed a family on such scant means”.

Dr Norman, a former Poole GP who lives in Lilliput, explains how unions, legal after the repeal of the Combination Acts, existed elsewhere in the country but Dorset landowners and farmers did not see them as acceptable and sought to “strangle them at birth”.

That led to the dramatic arrest in 1834 of Loveless and five other farm labourers who were to be made scapegoats. Thrown into prison in Dorchester to await the assizes, the charges hinged on the making of “unlawful oaths” with the scheming landlords, led by magistrate James Frampton liaising with home secretary Lord Melbourne.

Oh, and when it came to court to decide if the indictment should go ahead, Melbourne’s brother-in-law was foreman of the grand jury that included Frampton and his brother and step-brother.

No surprise then, that a trial would later go ahead where the Tolpuddle Martyrs – as they became known – were found guilty by another jury and the judge sentenced each to be transported to Australia for seven years.

Dr Norman compares the sentences they received with other prisoners at the same assizes where, for example, a Thomas Horlock was jailed for two months for stealing four fowl; a poacher was sent to prison, with hard labour, for intending to poach; and Jane Stacey got six months’ jail for murdering her bastard child.

Dr Norman also tells of how Frampton subsequently made the lives of the six men’s families who had lost their breadwinners “a perfect misery”.

The story of the Tolpuddle Martyrs’ grim experiences and the wave of protests in Britain that eventually led to their pardon, is well documented. (Within a week of their conviction, 10,000 protested in London.) But Dr Norman’s study adds to the insight by looking at how Methodism in Dorset was so influential in making a humble 19th century farm labourer like Loveless a highly literate, erudite man.

The six Tolpuddle Martyrs were pardoned in 1836 and, after their ordeals, only one returned to live in Tolpuddle.

Today, the story of the Tolpuddle Martyrs is famous worldwide but, writes Dr Norman, “nobody, until now, has been able to ascertain, precisely, where in the village of Tolpuddle the Loveless family lived”.

It was believed their cottage had been pulled down but the author disputes that.

Pacing out a position from available evidence he argues that it is “proved beyond reasonable doubt” that a cottage still standing in the village today (called Pixies Cottage) was where the Loveless family lived.

• The Story of George Loveless and the Tolpuddle Martyrs by Dr Andrew Norman, Halsgrove £12.99.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here