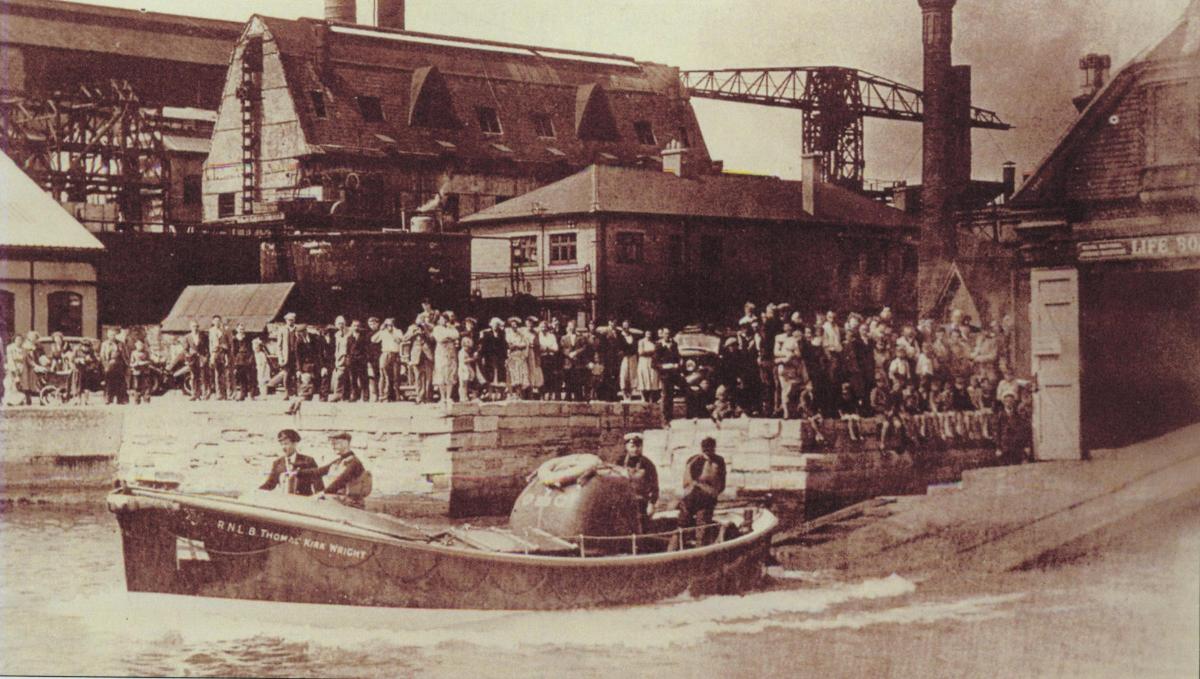

THE soldiers rescued from France as portrayed in Christopher Nolan’s movie Dunkirk owed a huge debt to the thrust made by British tanks – and their crews trained in Bovington Camp – five days earlier, writes historian Hugh Sebag-Montefiore

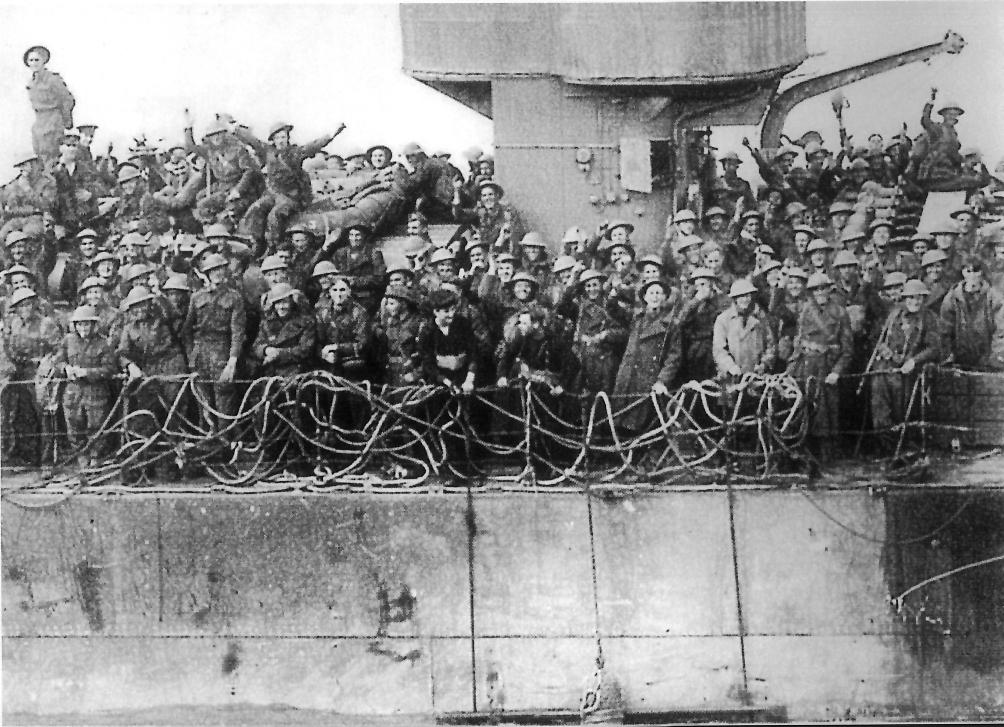

FIVE days before the start of Operation Dynamo, which was to rescue our troops from France, the British Army was on its knees. It was generally agreed that if the counter-attack planned for May 21, 1940 was not a success, the Army would be ‘stuffed’.

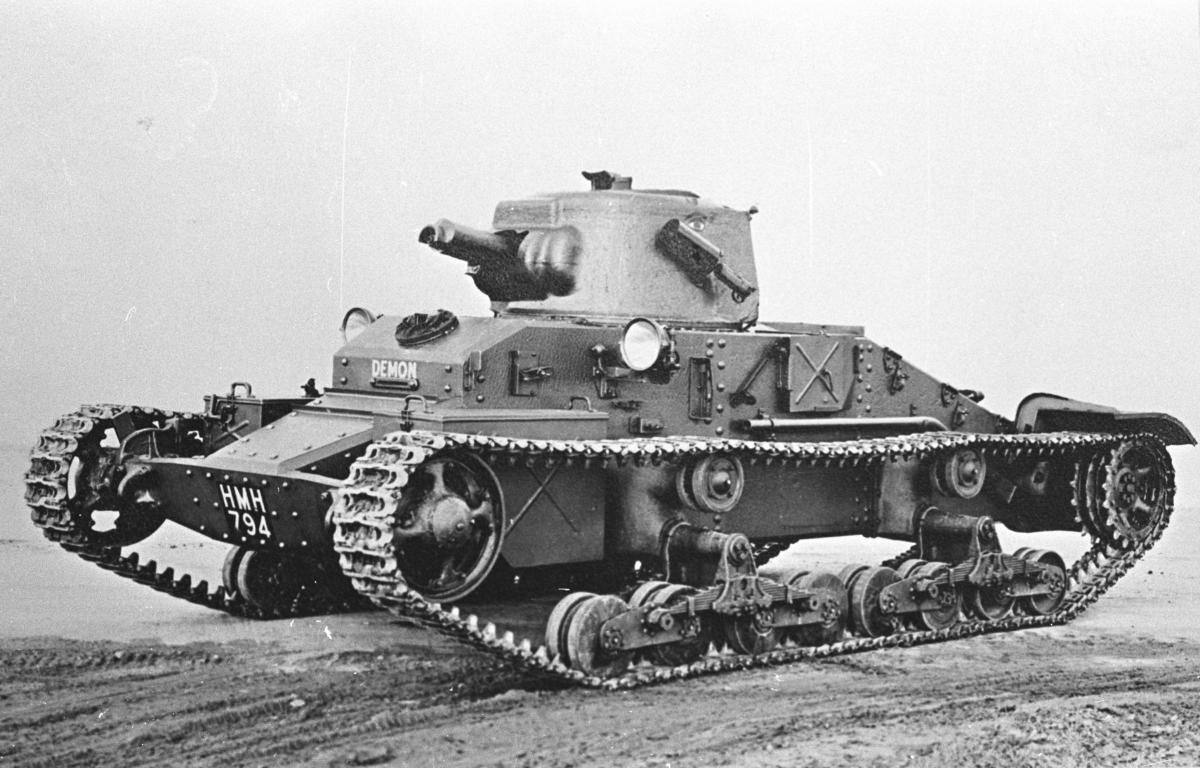

However there was a problem. The British Expeditionary Force could only field a force of 72 tanks, and just 16 of them were the real deal: Matilda Mark 2 tanks protected by 2 pounder guns. The Matilda Mark 1s had to make do with mere machine guns.

Nevertheless the right wing of the pair of attacks which were to skirt round the west of Arras, 40 miles south-east of Dunkirk, before advancing towards the east, was to have an extraordinary impact on events to come.

The account by Erwin Rommel, at that time a vigorous German major-general leading from the front, describes how he and his men in the 7th Panzer Division only stopped one group of tanks near the village of Wailly thanks to Rommel rallying the retreating gunners in person.

Rommel was lucky that most if not all the tanks he came up against were Matilda 1s. An even more audacious raid was made by a pair of the 7th Royal Tank Regiment’s Matilda 2 tanks commanded respectively by Major John King and his Sergeant Doyle.

According to King, the first danger he encountered was when a group of anti-tank guns 300 yards away fired at him: "They did not penetrate, so we went straight at them, and put them out of action. My tank ran over one, and I saw another suffer the same fate. Small parties of enemy machine gunners and infantry now kept getting up in front of us, and retreating rapidly, giving us good MG targets for about 10 minutes. There must have been about 150 altogether."

King encountered more threatening opposition when he and his crew came across four enemy tanks with a road block behind them.

"They were firing at the Matilda 1’s and when they saw me, the two rear tanks swung their guns round in my direction. We opened fire together, and I advanced up the road, Sgt Doyle following, but unfortunately with his fire masked by my tank. Their shells did not penetrate, but my 2-pdrs went right through them.

"By the time I reached them, two were in flames, and some men from one of the others were running over the fields. I passed between them, and went hard at the weakest part of the road block, which was composed of a traction engine and some farm wagons. We crashed through the farm carts.

"Some burning substance got through the louvres of my large forward tool-box, which is inaccessible from inside the tank, through which fresh air is drawn into the inside of the tank, and set fire to the oily waste, overcoats, etc. So we sucked in fumes and smoke, instead of fresh air from then onwards.

"My loader couldn’t stand the fumes inside, and had to put on his gas mask. My driver found the red-hot toolbox by his right side so unpleasant that he opened his front visor, and put on his steel visor and crouched down low. I opened the top to get some air and free some of the fumes and smoke from inside, but immediately the lid was hit, and some burning stuff fell into the tank, and onto my head, causing slight burns, and a splinter of metal lodged itself in the back of my neck. We put the fire out with Pyrene."

King’s account goes on to describe how, after shutting the turret lid for a while, he was forced to open it again in spite of the danger "as the fumes and smoke were getting us down". He only closed it up for a second time on discovering that the Germans were shooting at it, causing the "occasional round" to fall inside the tank.

Doyle’s account describes how King "called me up and when I got to him, he was on fire. His words were 'Doyle, let’s finish the job.' So in again we went, knowing we were outnumbered, and never had a chance of coming out of it… Then the fun started. I know at least five German tanks he put out of action and a number of trucks etc. You see we met a convoy, and did we have some fun!

"We paid the jerry back for the loss of the rest of the Company, and at about 8 o’clock, I saw him get hit in the front locker, but still he kept going. I myself was then on fire, but he must have been on fire for an hour or so. He would not leave his tank because we were surrounded by German tanks etc, so we just kept on, letting them have it."

It was the Matilda 2’s engine rather than anything done by the Germans which eventually turned out to be King’s undoing. Shortly after they crashed through the German road block, it, as he put it, ‘conked out’. King has described what happened next.

“We were then hit by something heavier, and the power traverse of the turret put out of action. At the same time, the force of the impact crashed my gunner, (Corporal Holland), against the turret side, his left arm breaking the hand traverse mechanism off the turret, and breaking his forearm in doing so. The turret was thus jammed with the guns pointing to the rear, having swung round to finish off the four tanks. …However Holland said he could carry on, and the driver was able to restart the engine.

"I was following a track across country when, on topping a rise, we came upon a German 88 mm AA gun - 30 yds off the track. He immediately started to depress on to me, and I speeded up into a sunken part of the track whose banks gave us complete protection. There were no signs of Sgt Doyle, so I decided to run out the other end of the sunken road, and hope that our direction would bring the gun in our jammed turret to bear on the AA gun. He knocked the top off the bank while we were stationary, but did not hit us. As we came out at the other end, we were lucky enough to get a burst of MG fire onto the gun, and he only fired one round which missed us.

"Then Sgt Doyle appeared, and opened up with his 2-pdr and put him out of action. We stopped for a breather, and opened up the top which was almost immediately struck by MG fire, and this time the burning stuff that fell in seemed to ignite the fumes, and the whole thing flared up, and then settled down to steady burning. We scrambled out, and dragged the driver from the front seat.’"

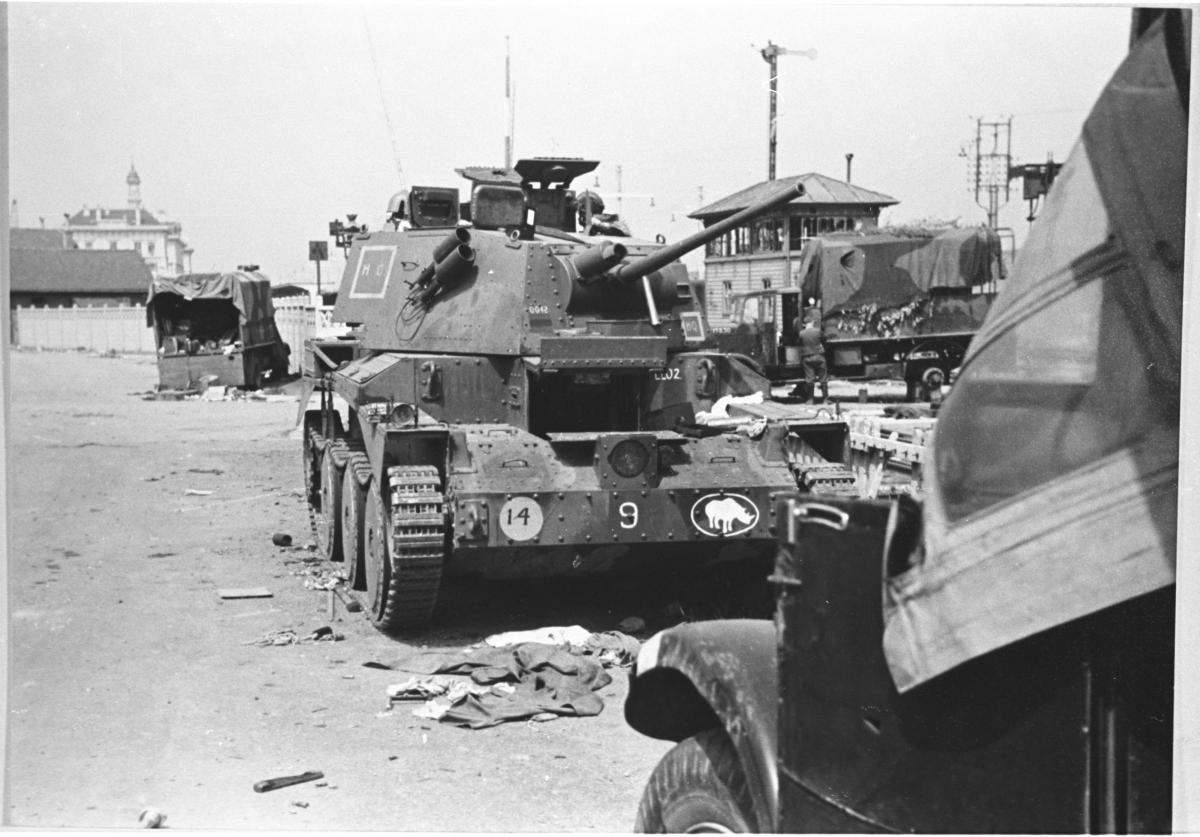

Doyle’s tank was also eventually put out of action, and given that the combined losses of the two RTR battalions amounted to in excess of 40 tanks, it was at first believed that the BEF was doomed.

Later it was learned that Hitler’s generals had subsequently twice halted his panzer divisions, because they were fearful that the Arras counter-attack would be repeated, more successfully. Ironically the cautious attitude was unwittingly caused by Rommel’s claim that he had been attacked by ‘hundreds of enemy tanks’ even though he was the last person who would have wanted a halt.

This delay was crucial: it gave Lord Gort, the British Commander-in-Chief, time to deploy some men both on either side of the corridor leading to Dunkirk, and around the Dunkirk perimeter itself.

Yet most of the cinema goers who queue up to see Dunkirk over the next weeks will be blissfully ignorant concerning the vital contribution of the men trained at Bovington Camp who made the evacuation possible. It does not get so much as a mention in the film.

The paperback and a new audiobook of the updated version of Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk: Fight To The Last Man are published by Penguin. The paperback of his book on the Battle of the Somme will be published in November.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel