A CENTURY ago this year, the awful stalemate of the First World War was broken by the arrival of a terrifying new invention.

The first tank was developed in utmost secrecy in Britain before being unleashed upon the German forces at the Western Front.

A new permanent exhibition at the Tank Museum in Bovington, opened recently by the Princess Royal, tells the human story behind this key moment in military history.

Tank Men: The Story of the First Crews, focuses on eight of the men involved. One of them was a Dorset miller whose role in a tank crew was revealed by the discovery of a photograph at a Poole church.

The First World War began with Germany’s invasion of France, via Belgium, in August, 1914. The advance was halted deep into French territory, prompting the Germans to dig themselves in to the most defensible land they had.

Between the lines of Allied and German trenches lay No Man’s Land, a narrow strip filled with barbed wire entanglements placed there by both sides. Attacking across No Man’s Land – with infantry facing barbed wire, machine gun fire and well dug-in troops – was incredibly costly in human life.

Britain was working on the invention of a “landship” that could cross No Man’s Land. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, was among those pushing for a mechanical solution to the impasse.

Experiments with commercially available wheeled and tracked vehicles led to the development of Little Willie, the world’s first tank, which is on display at the Tank Museum.

But Little Willie could not cross trenches, and the concept was re-designed – resulting in the familiar rhomboid shape of the First World War tank.

The prototype for the Mark I, known as Mother, could push through barbed wire entanglements and cross trenches. It was tried in January 1916, leading to an order of 150.

The building and training programmes took place in secrecy. Even the name “tank” was part of the subterfuge, intended to convince those involved that they were working on the construction of mobile water tanks.

On July 1, 1916, the Battle of the Somme began with a huge British attack on German positions. The British commander, Douglas Haig, had been keen to use tanks, but they were not ready, and he was under pressure to launch his attack early.

The resulting carnage became the enduring memory of the First World War, with 57,000 British casualties on the first day.

On September 15, tanks finally went into action in the last major offensive of the Somme campaign, at Flers-Courcelette. They were deployed, in groups of two or three, to punch holes in the German defences and destroy machine gun posts ahead of an infantry attack.

There had been 49 Mark I tanks due to take part, but only 32 made it to the starting line, the others having broken down or been ditched. Others were held up by shell holes or trenches, leaving only 18 to go into action.

The tanks pitched like ships in a rough sea as they crossed the cratered landscape, but they did their job.

The British press reported: “When the German outposts crept out of their dugouts in the mist or the morning of 15 September and stretched to look for the English, their blood was chilled to their veins. Two mysterious monsters were crawling towards them over the craters. Stunned as if an earthquake had burst around them, they all rubbed their eyes, which were fascinated by the fabulous creatures.”

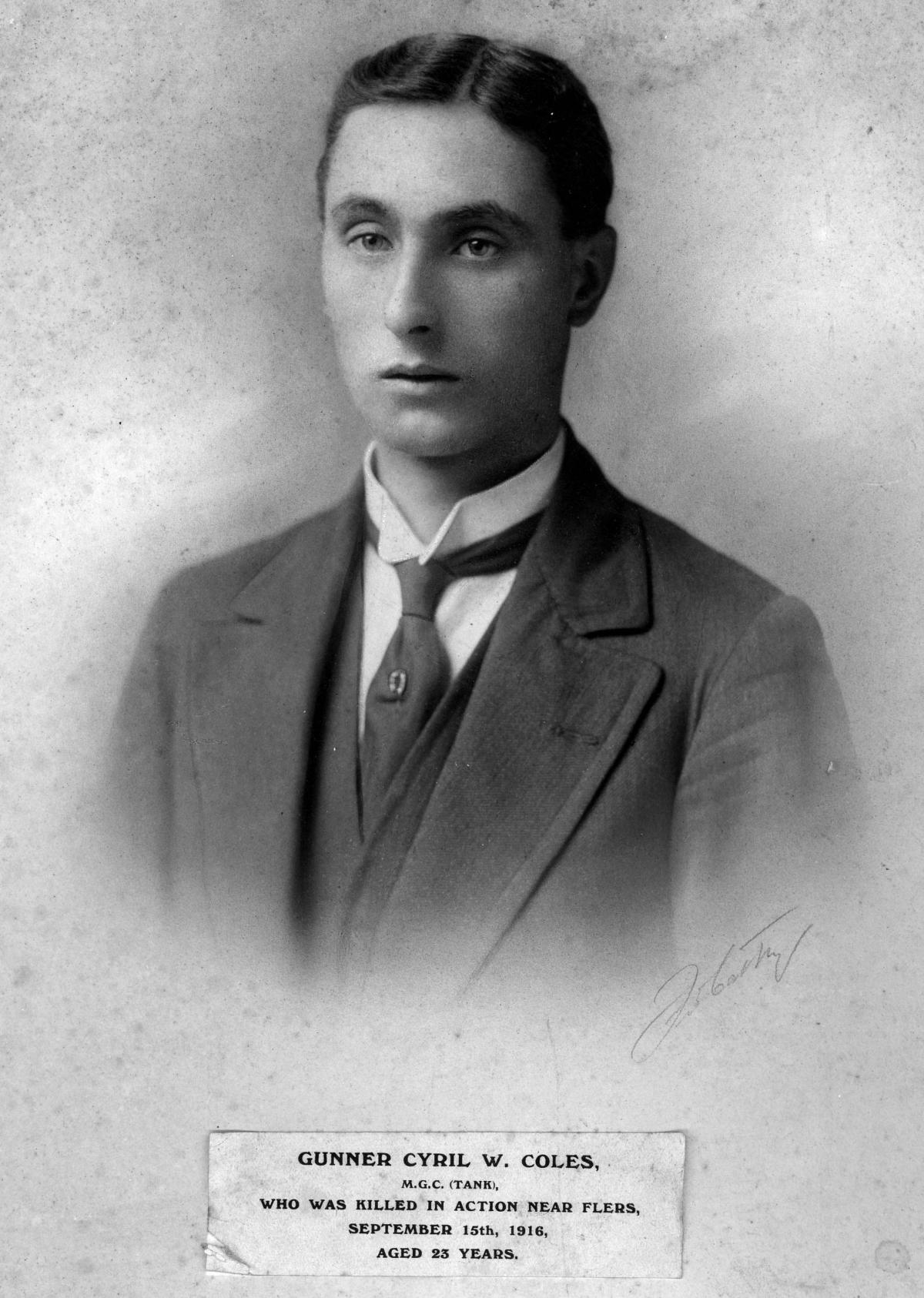

Among the men going into battle that Friday was Cyril William Coles, born at Canford in 1893. Census records have him working at Creekmoor Mill with his father in 1911 and he went to church near Poole Quay.

Cyril enlisted in the Army in February 1916 and went on to join the secret organisation that was to take the first tanks into battle. He trained for five months before becoming part of the eight-man crew of tank D15, which went into action that September 15.

D15 was struck and disabled by enemy artillery. The crew bailed out but faced German machine gun fire. Cyril died along with his fellow gunner and both were buried beside the wrecked tank.

After the Armistice, his remains were relocated to the Bull Road cemetery east of Flers. His brother Donald named his only son after Cyril in 1925.

Cyril Coles was included in the exhibition after a photograph of him came to light at Skinner Street United Reformed Church in Poole, labelled “Killed in the first tank attack at Flers September 15 1916”.

Melissa Lambert, who discovered the photo, to draw it to the attention of her sister Sarah Lambert, exhibitions manager at the Tank Museum.

Research identified Cyril in one of the first group photos of tank crewmen. This, together with census records and war diaries, enabled the museum to identify which tank he served in and what happened to him. His story can now be told alongside the other seven men who feature in the exhibition.

Sarah Lambert said of the eight: “These aren’t household names – they were just ordinary soldiers. They were chosen because their remarkable experiences illustrate dramatic and moving stories that have stood the test of time and continue to have a powerful and emotional impact today.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here