"I HAVE been blessed with health, happiness and a good memory. I have a duty to those who died to tell my story.”

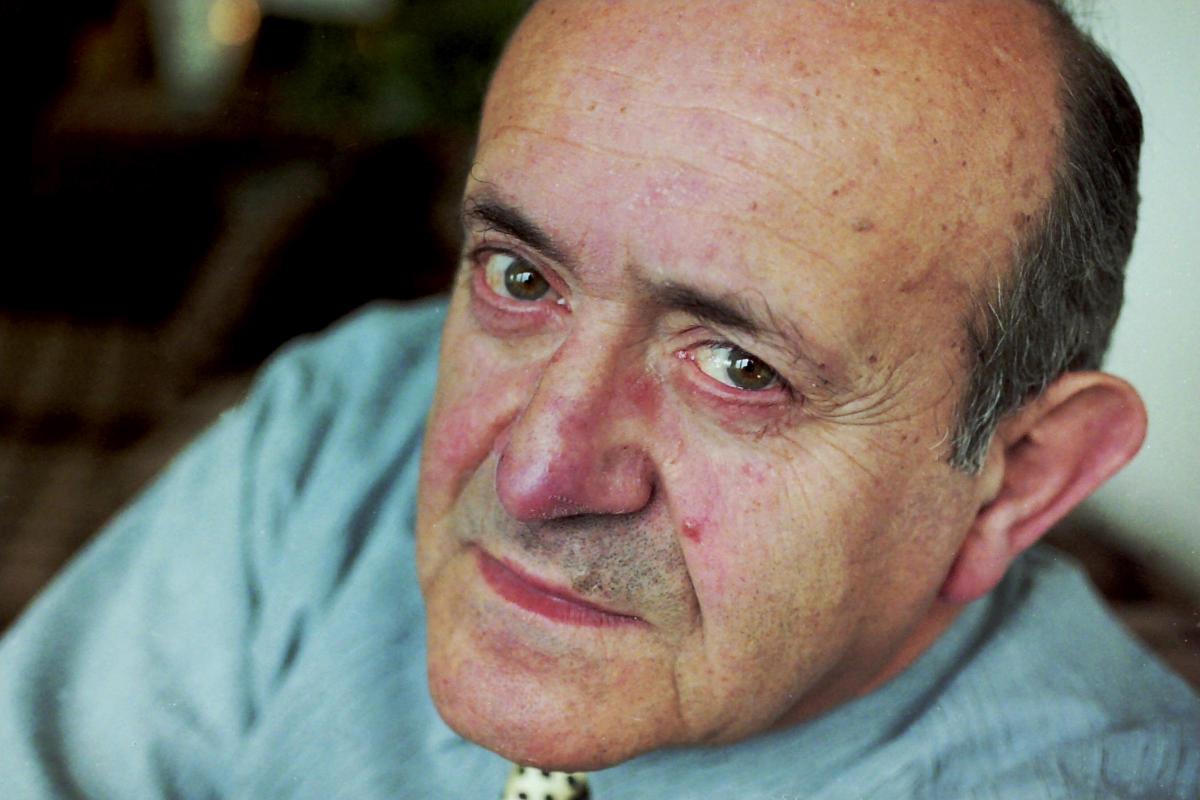

Those were the words of Mark Goldfinger, the Bournemouth man who did much of his growing-up in Nazi labour camps.

Mr Goldfinger, who died recently at the age of 83, was originally called Marek Goldfinger, and was nine when German tanks arrived in his home town of Rabka in Poland in 1939.

Sixty years later, he told the Echo’s Kevin Nash how his family fled and went to stay in Slomniki with Marek’s uncle.

The uncle was a ‘policeman’ in the Jewish community, whose job it was to strip all the items from homes left vacant by those sent to the gas chambers.

"My uncle would play cards with the SS officers. He was taken away for a few days and returned a broken man,” he recalled.

“We don't know what happened. He went back to play some more cards and didn't return. They shot him. Maybe he knew too much."

After three months at Slomniki, Marek and his sister Lusia caught an early morning train to Krakow with a cousin, a girl aged six.

Their mother, aunt and another cousin were due to follow on the next train. But before they could reach the station, they were rounded up with 60-70 other Jews and taken to some woods, where they were shot.

Marek knew his mother must be dead, but it took him 25 years to find out what had happened.

Lusia married a man from Rabka and fled on foot with false papers. She promised to send forged documents to Marek, who remained in Krakow with his young cousin.

The ghetto in Krakow was crammed with around 100,000 people and surrounded by a barbed wire fence.

One morning, Marek woke to see German troops lined up outside the fence. He and his cousin crawled through the wire to escape and hid on a pile of rubbish until danger passed, living on discarded potato peelings.

Luisa sent the documents she promised, but they were intercepted by two brothers who used them to get away.

Marek’s cousin was snatched and taken to Auschwitz. Marek was sent to a concentration camp, Plaszow in Krakov, ruled by commandant Amon Goeth.

"That man was evil. We would have to walk past him and he would choose who should die,” he said.

"One day he picked me. But it was hot and I had just slung my jacket over my shoulders. As he put his hand on me, the jacket fell off and I was carried away in the crowd. If I had been wearing that coat, that would have been the end of me."

Marek was taken to a labour camp outside Krakow and later to a munitions factory in Skarzysko.

"It was a horrible place. The chemicals turned everything yellow, your skin, your teeth, your hair, your nails, your eyes,” he said.

When the factory was being closed, the director singled out Marek to be shot. "A group of us were passing through a door and he pointed at me, but my supervisor pushed me back into the crowd and I was saved,” he said.

He was among those herded into railway goods wagons and taken to Buchenwald labour camp. For the rest of his days, he had a scar above one eye from a bullet which grazed him as he was being lifted from the wagon to reach for a turnip on another train.

He said of Buchenwald: "There were about 120,000 prisoners there, all nationalities. There were hardened criminals, murderers and rapists, conscientious objectors, prisoners of war, French MPs, members of the Italian royal family."

Marek, now 14, was one of around 20,000 prisoners left when Allied troops liberated the camp.

"I desperately wanted to live long enough to see the Germans beaten – and I made it," he said.

After liberation, Marek discovered his father Henry was a prisoner of war in Siberia. His brother George had been killed, aged 20, when his tank plunged over a ravine.

Marek became known as Mark and set up an engineering business in London with his father, who died in 1963.

In 1953, he married Sylvia, a German Jew who sailed to England on a coal carrier from Dunkirk.

Mark later used his knowledge of Polish, German and English to work as a police interpreter. He and Sylvia moved to Bournemouth around 20 years ago.

Mark used served on an international committee responsible for maintaining Jewish cemeteries. In 2004, he was thanked for his role in securing a memorial to the dead of the Belzec death camp in Eastern Poland, which operated for around 10 months in 1942.

He recorded several hours of memories for the Spielberg Foundation, set up by the director of Schindler’s List.

In 2006, it emerged that Werner Oder – whose Austrian father Wilhelm had set up a training school for SS death squads in Rabka – was living only a couple of miles from Mark.

Werner Oder was a minister at Tuckton Christian Fellowship and met Mark to express his remorse over his father’s past.

Mark said: " He is a decent man. He is totally ashamed about what happened even though he wasn't even born then.”

Mark continued to educate people about the Holocaust, speaking at schools and at Guys Marsh young offenders’ institution.

He was devoted to his twins, Jerrald and Michelle, and his five grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren.

"I get very sentimental with children, probably because between the ages of eight and 18 my own life was in turmoil,” Mark told the Echo.

Of his wartime experiences, he said: “Someone must have been watching over me to help me through. It must all have happened for a reason."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here