WHEN people want to debate human rights or the rule of law, Magna Carta is the name they often reach for.

This week, the Queen, the Prime Minister and the Archbishop of Canterbury were among an international party of VIPs at Runnymede near Windsor, to mark 800 years since the document was signed.

Magna Carta, or the Great Charter, was an attempt by King John to end a rebellion among unhappy barons – and it only laid down protections for the rights of those barons, rather than for the whole populace. What’s more, its practical significance was eroded as time went on and Parliament developed legislation. Yet it remains an epochal moment in history.

Lord Dyson, the Master of the Rolls, said at this week’s event: "Magna Carta has had its ups and downs. But it was a hugely significant step on a journey which led to the building of a society where everyone has equal rights and nobody is above the law."

And while Magna Carta, itself continues to inspire debate, Dorset and Hampshire can claim their part in its history.

The story of Magna Carta begins with the financial problems of King John, who had inherited the throne and large ancestral lands in France from his brother Richard I.

He lost most of those lands to France’s King Philip II in 1204 and spent a decade trying to regain them, raising taxes on his barons to finance the war. He was defeated in 1214, prompting many of the barons to begin organising resistance.

John travelled the country extensively in 1214-15, visiting Dorset a number of times.

Historical records show him securely established at Corfe from October 17-20 1214 and at Canford on October 20.

He was in Corfe again on December 3-4, and while there, he sent out instructions to a series of monastic houses about the election of new heads.

On December 4, he went to Sturminster – probably to the Sturminster Marshall manor of his friend William Marshal, rather than to Sturminster Newton. From December 6-8, he was in Gillingham, and the records show him travelling around 80 miles in six days – a wearying record of travel in days when roads were crude.

On or around December 6, the King sent out a summons to 12 knights from the counties of Somerset, Devon and Cornwall to meet him on January 1 as he sought to gain control over his kingdom.

On February 1-7 1215, John spent the best part of a week on the northern and western edges of Poole Harbour, possibly awaiting reinforcements in the shape of mercenaries from France, before travelling to Marlborough in Wiltshire.

He was in Canford on February 1, Corfe from February 1-3, Bere Regis on February 4 and Christchurch on February 5.

During that time, he granted – by the issue of letters patent rather than a charter – the rights for the men of Corfe to hold a weekly market in the shadow of Corfe Castle.

Corfe’s constable at that time was Peter de Maulay, who was from the Loire and had been exiled to England after the loss of John’s northern French lands in 1204. He was rumoured to have murdered Arthur of Brittany, King John’s young nephew.

On February 1, the King granted Peter letters of protection for himself, his men and his lands, so long as he remained in service with horses and arms. At the same time, the King was issuing instructions about his Irish lands, mostly transmitted to the Archbishop of London, who was his chief minister in the province.

In the early months of 1215, John sought more time, while hoping for backing from the Pope. But by the time he received that support, the rebel barons had become a military force and were to march on London.

John met the rebel leaders at Runnymede on June 10 and was presented with their demands for reform, called the Articles of the Barons. By June 15, both sides had agreed on the text of the Great Charter.

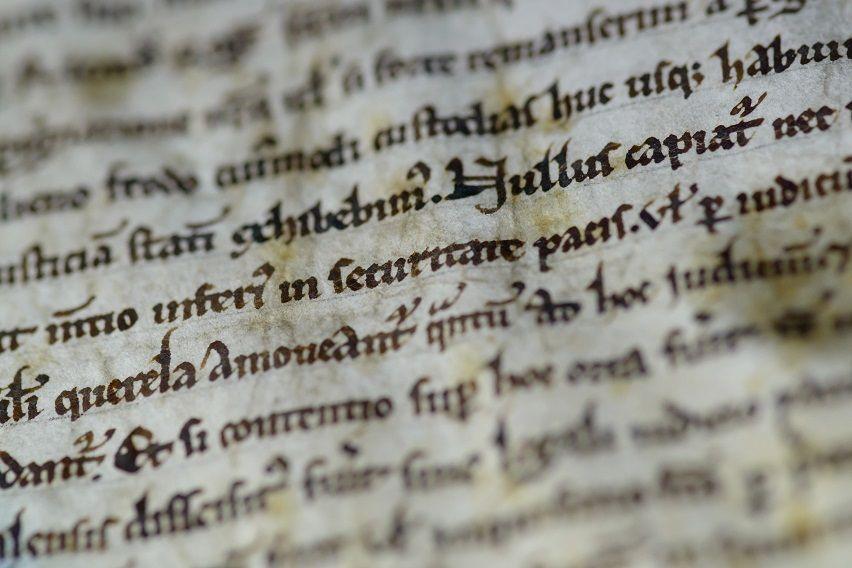

Its 60 clauses laid out key protections, including the right to a fair trial, to swift access to justice, and limitations on the King’s power to tax free men.

Several copies were written and sent around the country. Four of these survive, one of which is in Salisbury Cathedral, where visitors can see the marks on the vellum where King John’s seal was once attached.

Two Dorset men played a key part in the decision of the King to agree the Magna Carta.

One was William Marshal, who had become the King’s chief adviser in 1213. Marshal, born in humble circumstances in 1147, was described as “steering the reluctant monarch towards accepting the terms of Magna Carta, on which his mark appears first among those after the King”.

Marshal’s name is also preserved as a Dorset place name. Sturminster Marshall takes its first name from the River Stour and the name Marshall from William Marshal, who acquired the land there after marring the Earl of Pembroke’s daughter.

The other local figure with a link to Magna Carta is William Longespee, Third Earl of Salisbury. He was King John’s half-brother and had commanded the English forces that routed a French invasion fleet anchored at Damme in 1213.

His place in the Magna Carta negotiations is marked in the streets around Bearwood Primary School – King John Avenue, Knights Road and Runnymede Avenue.

Modern Dorset has been celebrating its links with the Magna Carta. Bearwood Primary held a medieval fayre recently, after a week in which the children learned about the events of 1215.

And Christchurch Culture and Learning Arena won £7,388 from the Heritage Lottery Fund towards the commemorations which took place there this week.

King John was a frequent visitor to Christchurch Priory and this week’s event included a re-enactment of his final visit, with pupils from Christchurch Junior School in costume and Bournemouth Shakespeare Players portraying the King’s arrival.

An exhibition by four local schools, 800 Years of Cultural Heritage, runs all week.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here