“AN ‘UNCROWNED King’ buried in Dorset,” read the headline in the Bournemouth Daily Echo, when the world said goodbye to Lawrence of Arabia.

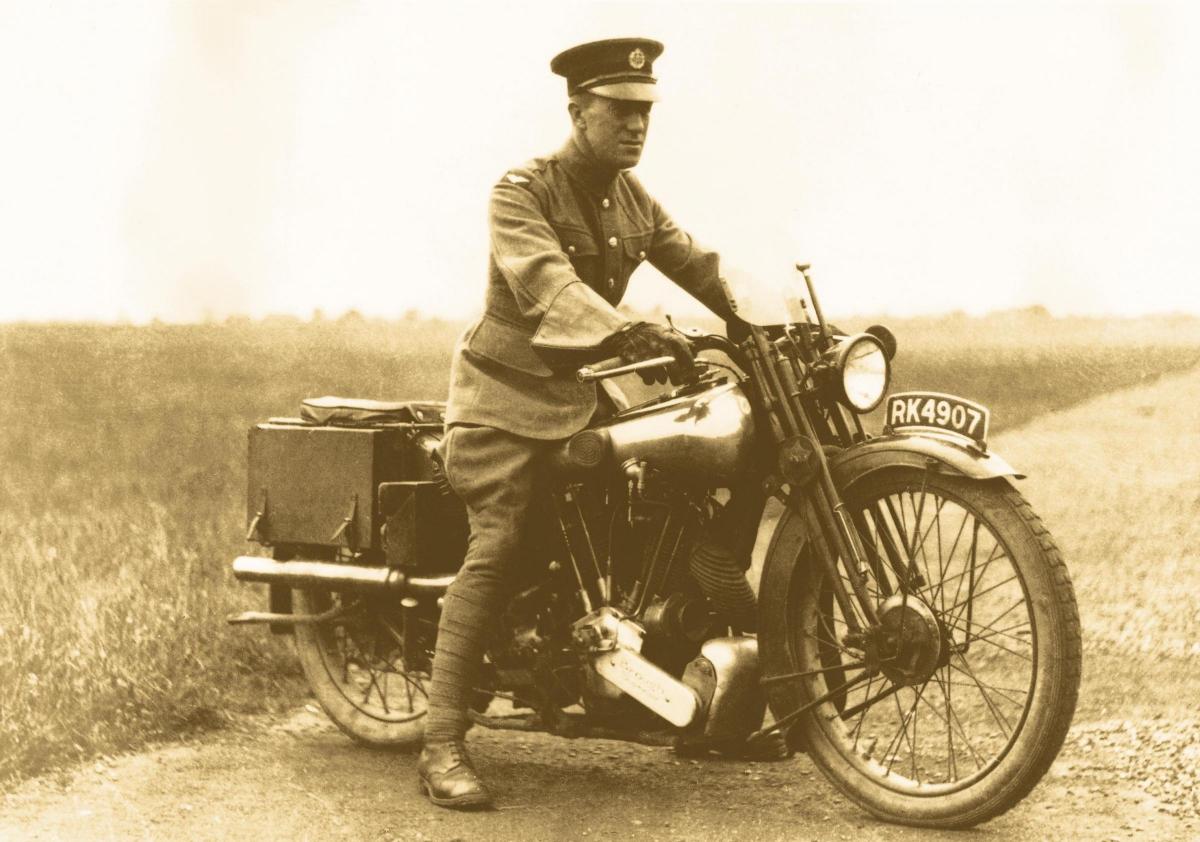

Eighty years ago today, TE Lawrence was riding his motorcycle along near his home at Clouds Hill when he swerved to avoid two boys on bicycles and crashed.

He died six days later at Wool Military Hospital, Bovington Camp, at the age of 46.

Lawrence’s exploits had enthralled the public during the First World War.

He was born in 1888, the illegitimate son of an aristocrat and governess. Beaten regularly by his mother, he built up his resilience by going days without food or sleep, and taking arduous hikes and cycle rides.

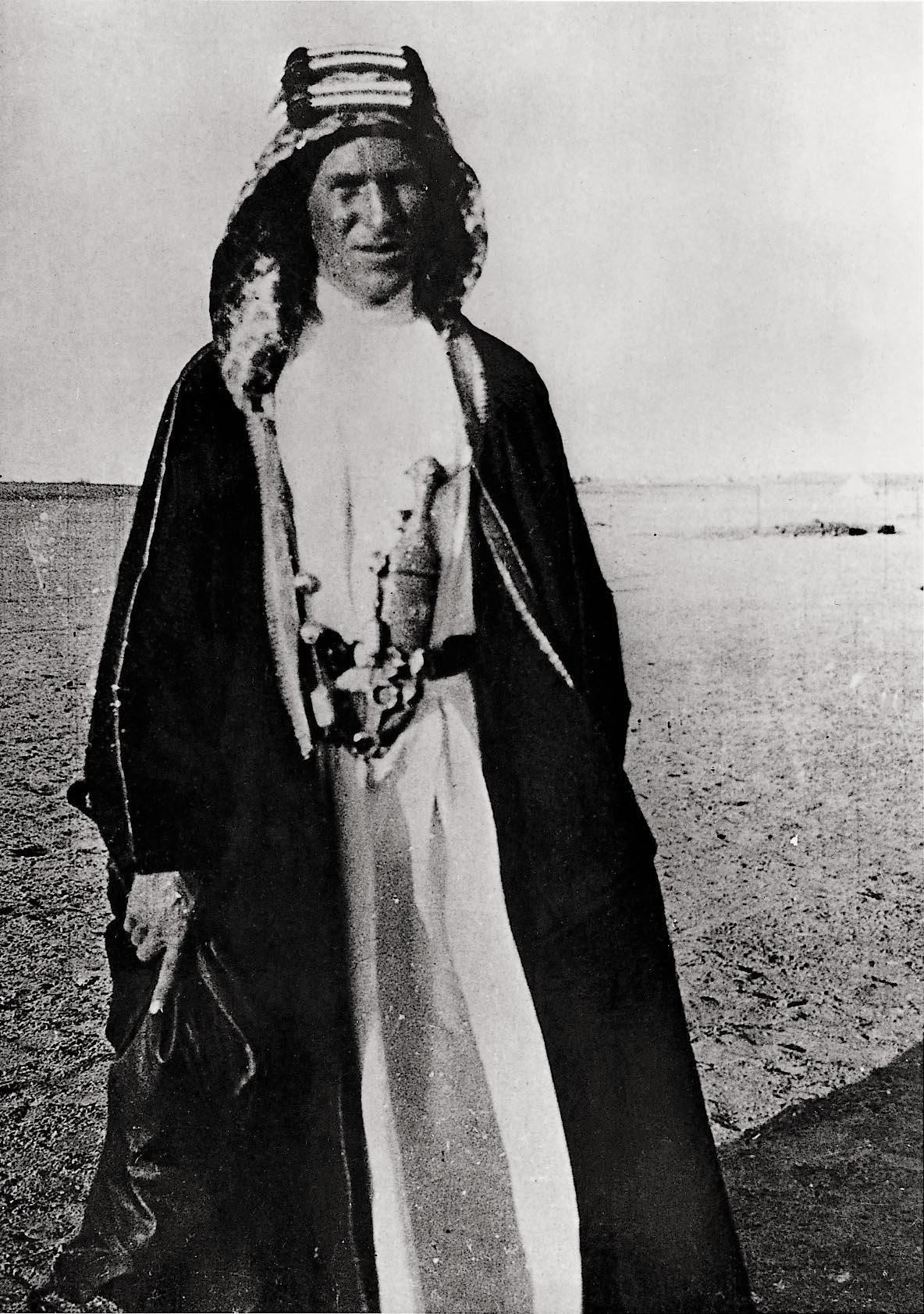

He visited Arabia as an archaeologist and came to despise the Turkish occupation of Arab land.

In the First World War, he was an intelligence agent in Cairo, promoting rebellion against the Ottoman Empire. He helped the Arabs carry out repeated attacks on the Hejaz railway, which was the Turks’ only way of supplying Medina, and in 1917, he arranged a successful operation to capture the port of Aqaba.

But when peace was settled, Britain and France partitioned the territory of the Arabs to whom Lawrence had promised independence.

Lawrence wrote a best-selling memoir, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, but rather than take high rank, he joined the RAF under the pseudonym John Hume Ross, before being exposed by the Daily Express.

Taking the name TE Shaw, he joined the Royal Tank Corps at Bovington, and lived in a cottage at Clouds Hill, near Wareham.

When he died, the Echo quoted at length Captain GE Kirby, superior officer to TE Shaw when he arrived at Bovington in 1923.

“He signed the necessary Army forms as all other recruits must, and was drilled with other newcomers for two months,” Capt Kirby said.

“His aptitude for clerical work resulted in the camp authorities drafting him to the quartermaster’s depot where he acted as storeman. There his daily duties were to hand out clothing and equipment to the men.

“That was his position during the two years he was at Bovington. He received no favours and asked none. He was very amenable to discipline, much more so than the ordinary soldier, and the fact that he had once been a colonel was never displayed in his behaviour. In fact he was a perfect Tommy Atkins.”

He added: “When he came he was never asked to give his reasons for joining the corps and they never came out while he was here.

“After he had completed two years’ service, he applied for his discharge and simply vanished into the blue.”

Lawrence had also paid visits to the elderly Thomas Hardy near Dorchester, the captain recalled.

The Echo reported: “In Bovington Camp and throughout Dorset the passing of Mr Shaw is regarded as a tragedy of the first magnitude.

“His death is a tragedy for England, even for the world, but none will feel it more keenly than the simple folk of the Dorset countryside, who were proud of the fact that he had chosen their county, and was, in fact, one of themselves in the simple mode of life he followed at his humble cottage on Hardy’s immortal Egdon Heath.”

The next day, the Echo reported on funeral that brought such famous names as Winston Churchill, Siegfried Sassoon, August John and EM Forster.

“In a tiny sunlit plot beside the River Frome, in the village of Moreton, in Dorset, Mr TE Shaw – ‘Lawrence the Uncrowned king of Arabia’ – was laid simply to rest to-day,” the report said.

More than 100 distinguished mourners were brought by train from London, and there was no room in the church for the general public.

Among the pallbearers was Pat Knowles, a “servant and friend who had shared Shaw’s last days of life in the little cottage nearby”, the paper said.

The family had requested that there be no flowers, but a girl dropped a bunch of lilac and forget-me-nots by the side of the grave, bearing the words: “To TEL who should sleep among the Kings.”

That day’s Echo also reported on the inquest that had taken place that morning at Wool Military Hospital, under coroner Mr R Neville Jones.

Shaw’s motorcycle, known as George the Seventh, was brought into the room, along with the bicycle of Albert Hargraves, 14, who had suffered minor injuries.

The inquest heard from Ernest Catchpole, a corporal in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, who said he was at Clouds Hill camping ground when he saw a motorcycle doing 50-60pmph.

Just before it got level with the camp, it passed a black car travelling in the opposite direction, the corporal said.

“Next I saw the motor-cycle swerve across the road to avoid two pedal cyclists who were proceeding in the same direction from Bovington,” he added.

However, neither errant boy Bert Hargraves, of Somme Road, nor his friend Frank Fletcher, 14, of Elles Road, Bovington Camp, could recall seeing a car, and the police could not trace one.

It was one last mystery in the life of one of the century’s most enigmatic men.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here