A UNIQUE correspondence carried out with the aid of hot air balloons and carrier pigeons tells the story of an Englishman’s life in besieged Paris.

The letters, newly published as a book by a Bournemouth author, were written throughout the siege of Paris from 1870-71, during the Franco-German War.

Historian Ashley Lawrence bought the correspondence at auction 14 years ago and embarked on years of research which eventually revealed that the Englishman, William Brown, ended his days just miles away in Hampreston, near Wimborne.

His research would also bring him into contact with the letter-writer’s great-grandson, who believed the correspondence was long-lost.

“I’ve always been interested in postal history and stamp collecting,” said Mr Lawrence.

“A friend alerted me to the fact that this particular collection of letters was coming up at auction at Spink’s.

“This was about 2000. I didn’t realise, at the time, I would be spending the next 14-15 years researching them and that there would be a book at the end of it.”

William Brown, who turned 34 at the start of the correspondence, was living in Paris, where he was in partnership with Frenchman Christopher Jourdain, running an outfitters called the British Warehouse. The Franco-Prussian war broke out in July 1870 and Mr Brown took his wife and two young daughters to England before returning to Paris at the start of September.

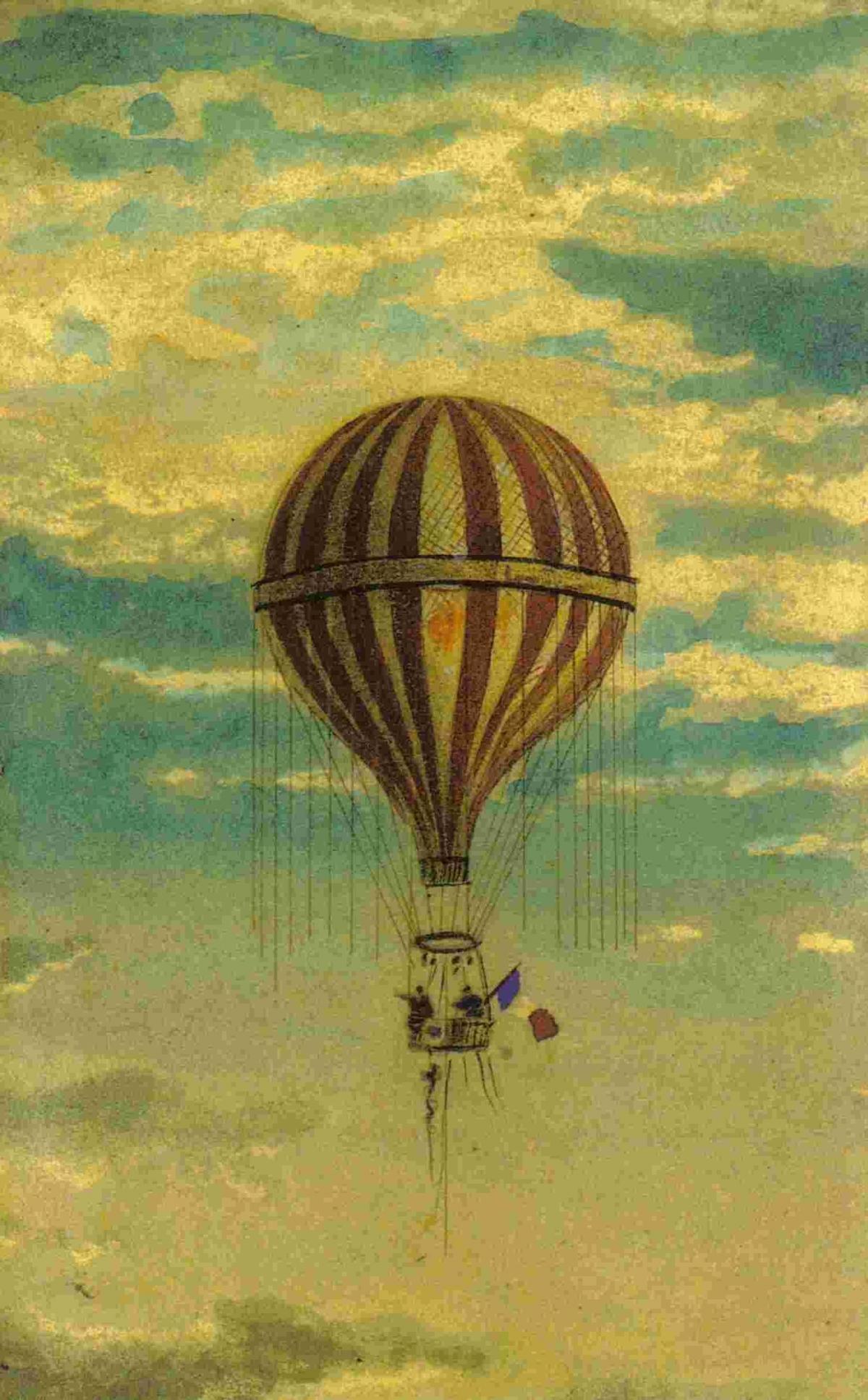

On September 23, the first of 67 hot air balloons left Paris carrying post for the outside world, with a letter of Mr Brown’s among the mail. Some of those balloons were to land in occupied territory and two were lost at sea, but a great deal of correspondence got through.

However, the letters from Mr Brown are unique for offering such a vivid account of the whole period in English, right up to the Paris Commune – the revolutionary socialist that governed briefly after the war.

“It covers the whole period of the siege from the start of it, when he gets back to Paris, right to the end of the siege and through the Commune period. It’s completely documented,” said Mr Lawrence.

“It’s the best example I’ve come across of an Englishmen’s account of the siege.”

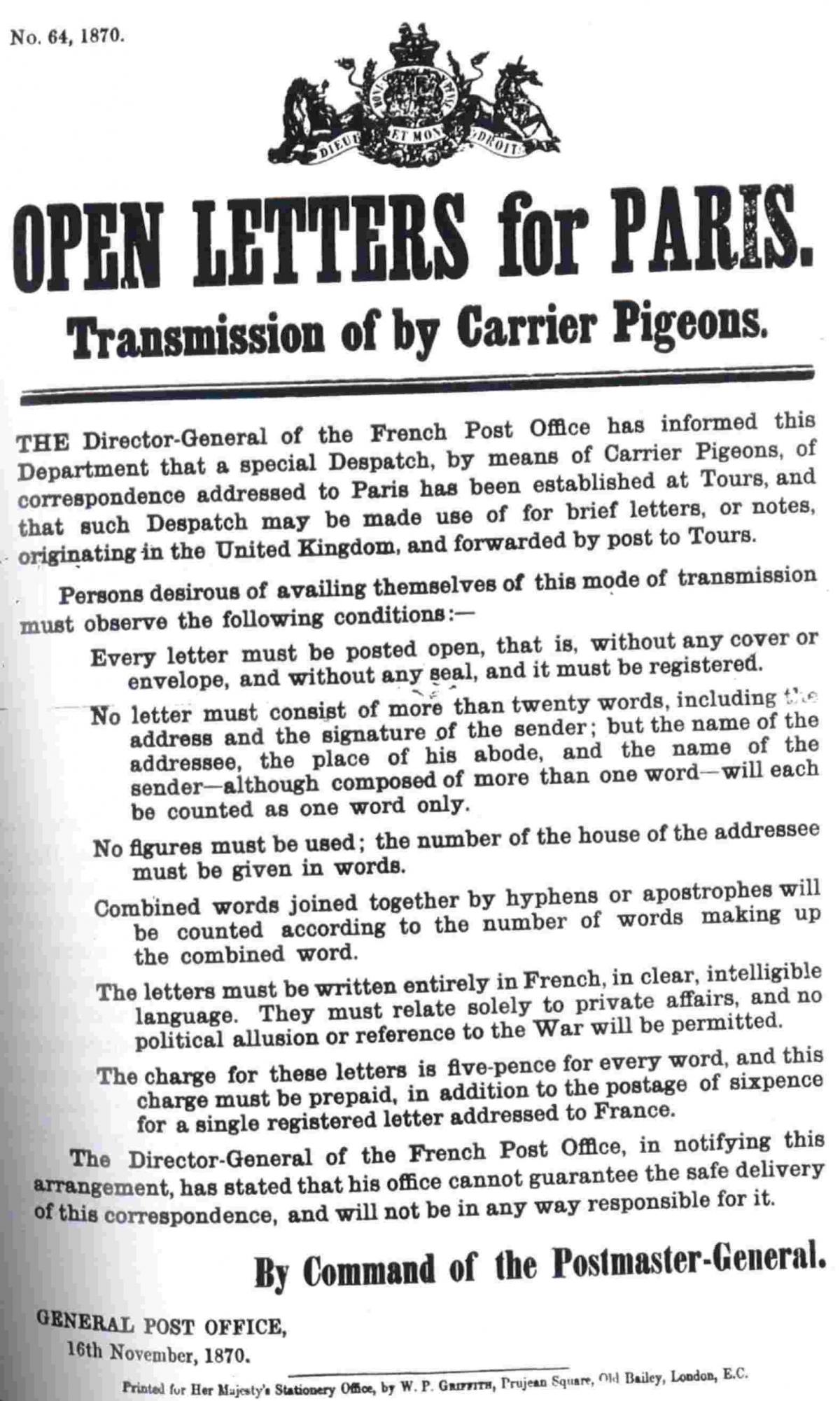

Getting post into Paris was even more complicated than getting it out. Mrs Brown’s few replies were microfilmed and sent by carrier pigeon.

William Brown’s letters describe powerfully the atmosphere in Paris. On September 11, with the siege looming, he wrote: “Paris is all bustle but not gay. The absence of street sweepers and water and the abundance of dust gives the gay city the air of a ballroom at 6.00am. It’s terrible to see the thousands of Gardes Mobiles with guns wandering about. Everybody seems bent upon resistance and unless some foreign powers interfere it will be a terrible end to a disastrous war.”

Five days later, he wrote: “There is an order issued this morning that on Thursday, 6.00am, the gates will be finally closed, and no-one allowed to leave or enter the city without a special permit. We have orders to lay in as much water as possible, and with that and my provisions which are to hand, I shall not want.”

On September 23, he reported his Englishness causing some trouble. “I had the misfortune to ask a stupid Garde Nationale the way to a certain place, when the fool took me for a Prussian and walked me off to the Commissaire of Poilce, where I was examined and soon set at liberty with apologies.”

“I am to have a pass from the Mairie so as to avoid a recurrence of such a disagreeable proceeding.”

His letters, often addressed to “My Dear Old Sweet” or “My Dearest Old Pet”, repeatedly assured Mrs Brown and his “little chicks” not to worry.

But sometimes the tone darkened. On October 3, after the fall of Strasbourg and Toul to the Prussians, he wrote: “Next, I suppose, will be Metz or her brave army, and then, oh then the final struggle. Will Paris, Paris the gay and beautiful, the centre of attraction not only of Europe but of the world, be successful, or perish, or both. We have thousands of brave hearts ready to die rather than see her fall a prey to the foreigners.”

Food supplies ran down as the siege continued. In November, Mr Brown reported that horse meat was being eaten and that “the French cooks make the best of it”, while “the flesh of the mule and ass is equal to veal”. In “some of the lower quarter”, cats and rats were being eaten. In January, he reported that the zoo had slaughtered its animals for lack of hay, so Parisians were dining on “steak of elephant with sauce piquant” as well as camel and bear.

Continuing Prussian bombardment and the failure of Parisian attempts to break out of the siege led to a surrender and armistice that month. But while he was pained by the defeat – and by German plans to hold a victory parade through the city – Mr Brown was glad his family would be reunited.

On February 24, he wrote: “If peace is signed by the time you get this, pack up and prepare to leave for the end of next week.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel