MONTHS after the successes of D-Day, there came a devastating and unexpected defeat for Britain and a victory for Germany.

The Battle of Arnhem, in September 1944, produced the same kind of heroism and resolve seen at the invasion of Normandy, but with a tragically different outcome.

The 4th and 5th Dorset Regiments and the 7th Hampshire Regiment both played key parts in the ill-fated mission.

The Allies had swept through France and Belgium in the weeks after D-Day and were set to enter the Netherlands.

Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery devised a plan to drop thousands of paratroopers behind enemy lines, where they would hold onto key road and rail bridges until advancing tanks could relieve them.

But the operation ran into trouble soon after it started on September 17.

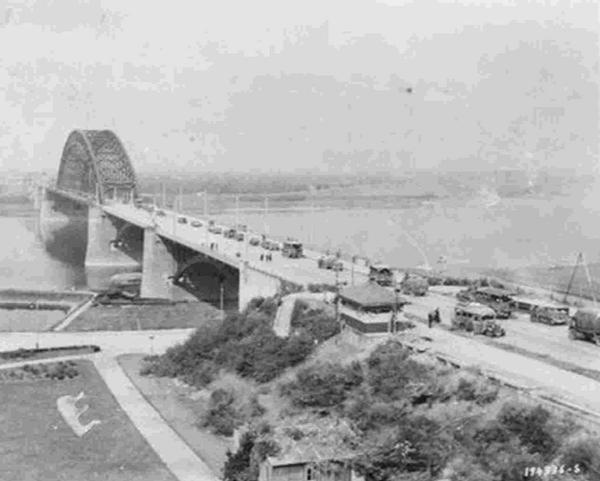

The armoured columns of Britain’s XXX Corps had only one route to the bridge where they were to link up with the paratroopers – a narrow, treacherous route nicknamed the Devil’s Highway by the troops.

The two Dorset regiments, part of the 43rd Wessex Wyvern Division, struggled to reach the Rhine at Arnhem, suffering 220 fatalities in a few hours. The prisoners were sent to Stalag XIIA at Lumburg.

Less than a third of Allied troops would survive the battle.

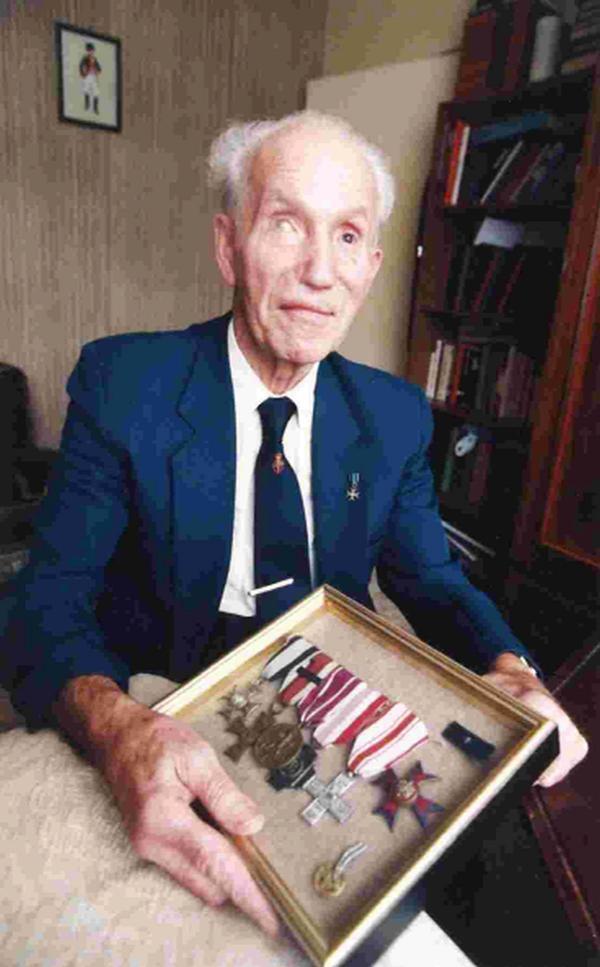

Among those who did was the late Henry Cluett, a front gunner and driver with the Coldstream Guards.

Many years later, in his home at Hamworthy, he told the Daily Echo of his memories of the crash-landed gliders which had delivered troops to the battle zone.

“I climbed up into one glider and found a bullet-proof vest full of bullet holes.

“I wore it for two or three days but began to feel ashamed of myself for having protection my colleagues didn’t have, so I took it off,” he said.

He was escorting some prisoners when a shell landed in front of them, sending a piece of shrapnel through his clothes and into his makeshift cigarette case. Mr Cluett, who died in 2009, kept the case and the cigarettes which may have saved his life.

Sgt Major Laurie Symes was with the 7th Hampshire Regiment’s D Company.

It took five days for the regiment to reach Nijmegen, a few miles from their objective at Arnhem. But the British 1st Airborne Division was in tatters and XXX Corps could not break through.

The Hampshires dug in along the Rhine Dyke, parallel with the River Lek.

On October 1, the Herman Goering battalion of the SS crossed the Lek and occupied the nearby brick factory, in what Allied commanders feared could be a bridgehead for a counter attack.

For four days, the Royal Hampshires attacked the factory, where dozens of machine gun nests were established inside the kilns.

On October 4, Sgt Major Symes and the 131 men of D Company launched a dawn raid on the factory in thick mist.

Sgt Major Symes’s best friend, Captain Hank Anaka, picked up a machine gun and charged an enemy strongpoint, but died in a hail of bullets. He was 26.

Speaking to the Daily Echo at his Christchurch home in 2005, Mr Symes recalled: “The terror is waiting to go into battle, that’s when you’re frightened. All sorts of things go through your head. You worry whether you are going to let down your men or yourself.”

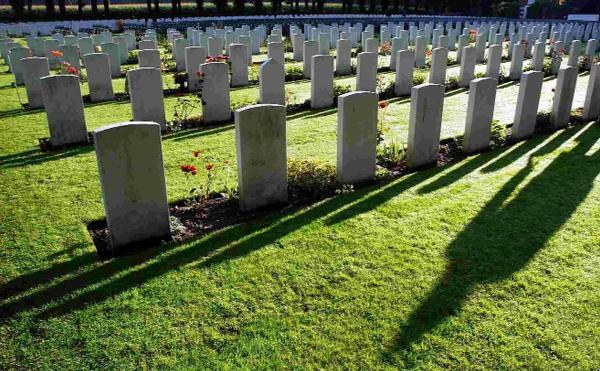

In later life, Mr Symes became national chairman of the Market Garden Veterans’ Association. He made an annual pilgrimage to the cemetery in Holland where his friend was buried, until his own death in 2012 at the age of 92.

Among the other Dorset residents with a connection to Arnhem was the Polish-born Wimborne doctor Stanley Sosabowski.

His father, General Stanislaw Sosabowski, played a key part in the battle and was later portrayed by Gene Hackman in the 1977 film A Bridge Too Far.

General Sosabowski was the only senior commander to question Montgomery’s plan for Operation Market Garden.

Yet, on September 21 1944, when the fight for Arnhem and its bridge was already lost, it was his duty to lead the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade into battle.

German soldiers were waiting at the drop zones with their machine guns.

Stanley Sosabowski, speaking to the Daily Echo decades later, told how his father had considered asking for written orders from the Deputy Commander of the allied Airborne Army, Lieutenant General Frederick Browning, stating that he was forced into action.

The end of the war was awful for General Sosabowski. He had hoped to be involved in the liberation of Poland and was devastated that the western allies decided to let the Soviet Union retake his homeland.

His son, Stanley, was blinded by a German sniper during the Warsaw Uprising of 1944 and his disfigured face had to be reconstructed.

Speaking to the Echo at his Wimborne home, Stanley Sosabowski said; “My life is not important. But my father, he was a hero.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here