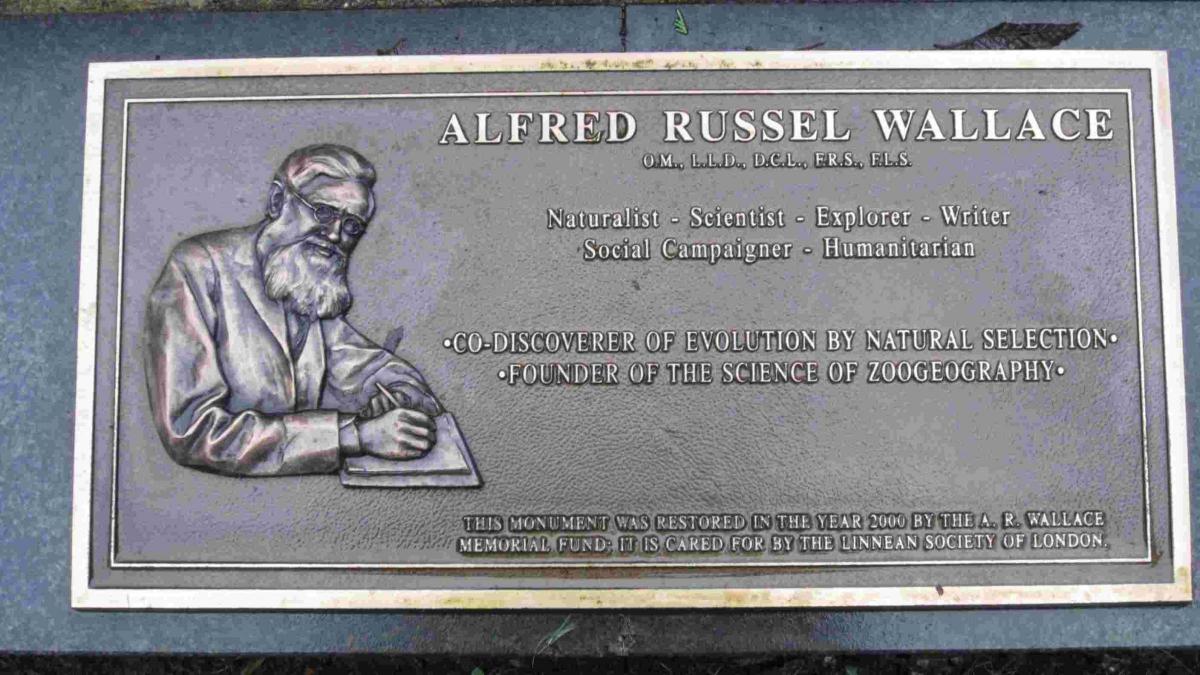

SCIENCE enthusiasts around the world have been remembering Alfred Russel Wallace, who died 100 years ago this month in Broadstone.

At the time of his death, he was probably the most famous scientist in the world. His family were offered a funeral service at Westminster Abbey, although they decided he should be buried in Broadstone Cemetery.

But Wallace’s reputation was later eclipsed by that of his contemporary Charles Darwin, whose name was given to the theories of evolution they both promulgated.

JOHN CRESSWELL of Bournemouth Natural Science Society looks at his life.

ALFRED Russel Wallace has been called ‘Darwin’s moon’ and ‘the man in Darwin’s shadow’.

Many feel he should deserve the honours that Charles Darwin received for the Theory of Evolution that has shaped science for the past 150 years.

Wallace was born on January 8, 1823 in a cottage at Llanbadoc in Monmouthshire, although the family moved to Hertford when he was five. His middle name spelling of ‘Russel’ was due to an illiterate clerk.

As a teenager, Alfred learnt skills from his brother John, an apprentice carpenter in London.

In 1837, he joined another brother, William, to learn surveying and became interested in geology. Lack of work enabled Alfred to follow his interests in botany and zoology.

He was later forced to go to Leicester to teach. There he met Henry Bates, who was an apprentice but more interested in entomology. Alfred started to collect insects as well as plants.

It was reading William Edwards’ A Voyage Up the Amazon that inspired Wallace and Bates to go to Brazil, to the Amazon rain forests, in 1848.

Wallace stayed there some four years collecting insects which were shipped back to Britain.

There, he met the botanist Richard Spruce and they would discuss evolution around the campfite.

Explorers like Wallace were discovering whole ranges of animals and plants and Wallace was honoured for his discoveries by having many species named after him. He went on to travel to the Far East, where he spent three months finding some 700 species of beetles.

Dismayed by a paper by Edward Forbes, who was a Creationist, Wallace spent the rainy evenings writing notes for a book with a working title of The Orgnaic Law of Change. He sent a draft of his Sarawak Law back to England, where it was published in September 1855. His agent told Wallace to concentrate on collecting and stop ‘theorising’, but those who read the paper realised Walalce was saying the same thing as Charles Darwin, already an established naturalist.

Later, Wallace wrote to Darwin expounding his ideas of how evolution could be driven by natural selection.

When Wallace’s manuscript reached him on June 18, 1858, Darwin reacted with amazement and despair.

The concept was almost identical to that he had been developing for several years with the view of publishing a large volume. Darwin realised Wallace’s paper would pre-empt his work but felt honour-bound not to suppress it.

Charles Lyell and Joseph Hooker suggested the best compromise would be to read Wallace’s paper, together with a couple by Darwin, at a meeting of the Linnean Society on July 1, 1858. It was the greatest revolution in our understanding of the natural world, but the full public impact did not really come until Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published in November 1859.

Wallace remained in South East Asia until 1862, continuing to collect, yet unaware of the controversy that the Theory of Evolution had caused at home.

He had amassed a small fortune from the sale of his tropical collections of birds, beetles and butterflies.

He was quite happy to let Darwin expound the doctrines of evolution, although he was to give several lectures and write on the subject, which by then had acquired the title of ‘Darwinism’.

He studied spiritualism, astronomy, comparative religion and campaigned on socialist issues such as land reform, rights for women and railway nationalisation and wrote against capital punishment, militarism and capitalism.

After a lecture tour of America, he decided to settle down and eventually found a home in Corfe View, Parkstone, and moved in midsummer 1889.

His garden was supplied with plants from Gertrude Jekyll, Kew Gardens and orchids from Singapore.

Unfortunately, Corfe View became surrounded by development, so Wallace searched for new space.

He found it just four miles away in Broadstone, in an old orchard of apple, pear and plum trees, with views over Poole Harbour to the Purbeck Hills. His family moved in on Christmas 1902, just before his 80th birthday.

Wallace belonged to the local Spiritualist Church and was the first honorary member of Bournemouth Natural Science Society when it was formed in 1903.

He received the Order of Merit in 1908, the highest civil distinction bestowed in Britain.

He absented himself from a Buckingham Palace investiture and a King’s Equerry travelled to Broadstone to present the medal.

Wallace was the first recipient of the Darwin Medal. The last years of his life were still prolific, with many books published.

Late in 1913, Wallace grew weaker.

He would tour his garden in a wheelbarrow pushed by the gardener. He fell ill on November 2 and died on November 7. A funeral at Westminster Abbey was turned down by his family.

Instead, he was buried in Broadstone Cemetery. A fossilised tree trunk from a Dorset beach has been erected on his grave.

A Poole Pottery plaque was placed on Old Orchard, but soon after the house was pulled down and replaced by Wallace Road.

Bournemouth Natural Science Society took charge of his plaque and it now hangs in the reference library.

More information about Wallace is at wallacefund.info

Wallace's Dorset Legacy

Wallace’s name has been given to a host of places and discoveries, from a boundary separating zoogeographical regions in Asia to a crater on Mars.

But there are several local tributes to the great scientist.

Bournemouth Unviersity has a Wallace Lecture Theatre.

Bournemouth Natural Science Society has a Wallace Room. Wallace House is the name of a health centre in Broadstone.

Bournemouth has a Russel Road.

The road near the site of Wallace’s long-demolished house, Old Orchard, in Broadstone, is called Wallace Road. A block of flats in Broadstone is named Wallace Court.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here