IT was perhaps the bleakest day in Bournemouth’s history.

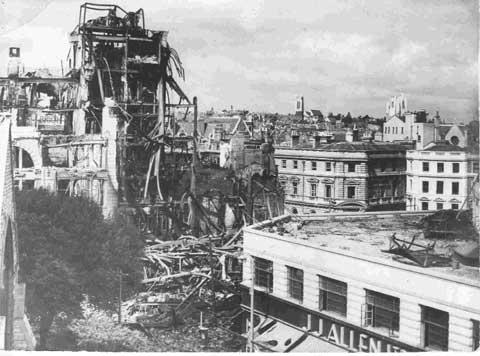

A German air raid lasting only five minutes killed at least 130 people, with the wrecked buildings including the Metropole and Central hotels, Beales, Cairns House, West’s Cinema and the Shamrock and Rambler coach station.

The 70th anniversary tomorrow will see a memorial unveiled at Lansdowne Crescent at 12.50pm.

Meanwhile, an exhibition at the Bournemouth Natural Science Society, 39 Christchurch Road, runs tomorrow until Saturday, 10am-4pm.

John Creswell, historian and member of the Civil Defence Association, tells the story of the civilian heroes of the tragedy, while Darren Slade reports on how a researcher has produced a set of biographies of that day's dead.

The iconic photographs of the Metropole and Central hotels after the tip-and-run bombing raid of May 23, 1943 show dozens of people in tin hats scrambling over the ruins.

These men and women are the unsung heroes of this and 50 other raids on Bournemouth during the Second World War.

As war clouds loomed during the 1930s, the British government set up an extensive body of volunteers capable of meeting the expected devastation of aerial bombing. The scheme was termed Air Raid Precautions (ARP), later known as Civil Defence.

At the council level, Alderman Harry Mears created a loyal team.

The scheme was built around the wardens, who for five-and-a-half years were continually on call.

During a raid they would coordinate the rescue of victims, the need for making safe the properties and ensure the subsequent resumption of traffic.

Their teams and power of authority embraced first aiders, firemen, heavy rescue and repairmen, the police and Home Guard.

Their success lay in networking. The main control centre was in the basement of the Town Hall, which was linked to three divisional centres – at Fairlight Glen in Avenue Road, the Embassy Club in Brassey Road, and Shelley Manor, Boscombe.

Each division had several zones focused on a warden post, from which teams of local wardens monitored their designated area.

At each bomb fall, a team of helpers would be assembled to meet the needs of the damage; an ambulance, fire tender or police officer could be called, and manpower was tailored to the incident, so that those not required could remain on standby in case of a potential second raid.

Whilst some of the groupings and personnel were paid, the majority were voluntary.

Various other voluntary organisations worked with ARP, such as the Red Cross and St John Ambulance brigade, the Women’s Voluntary Service, Fire Guards, Salvation Army – and even an Animal ARP for bombed-out pets.

However, it was sometimes necessary to call in the Home Guard and police to protect damaged property from looters.

For much of the time, the volunteers were obliged to be in a state of readiness with little to do. But in an emergency they gave their all, at times losing their lives and homes.

At the end of 1944, the bombing threat had diminished and Civil Defence were stood down, and their colours laid up in St Peter’s Church.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel