THE huge losses suffered by British soldiers as they tried unsuccessfully to break through the German line on 1 July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, 100 years ago this month, have been well documented. But the battle continued for more than 4 months.

In his new book Hugh Sebag-Montefiore also describes the torment suffered by the commander of one of the British tank crews who as part of the ongoing attempt to break through the German Somme defences discovered they were up against, for the moment at least, an unbeatable foe.

It is based partly on the lecture given by this tank commander at Bovington Camp, where the tank units were based by the end of 1916

BASIL Henriques, a 25 year old lieutenant, was the commander of a 7 man tank crew during the Battle of the Somme.

He, along with the commanders of 47 other tanks, had been ordered to mount the first ever tank attack in support of infantry on September 15, 1916.

Experience would later prove that tanks did better if they attacked the same target in large numbers.

During the Battle of the Somme it was assumed that small tank units would prevail over German infantry.

The commander of Henriques’ group of three tanks had been told that at zero hour, 6.20 am, they should advance towards the German Quadrilateral strongpoint between the Somme villages of Ginchy and Morval.

Henriques later claimed their chances of overcoming the German gunners in the strongpoint might have been stronger had they been better prepared.

Incredibly, he and his crew had only worked together in a tank on one occasion before they were shipped to France. They had never tried out the guns in the tank allocated to them before going into action. Nor had they ever fired any guns on a tank that was moving.

Their prospects were further diminished after the two other tanks in his group broke down. Nevertheless during the early hours of September 15, Henriques ordered the driver of his tank to move up to the British front line.

On the way, the tank had to be driven down a sunken road which was covered with the bodies of dead Germans. That involved driving over their corpses which already stank even before they were squashed by the tank’s tracks. However the tank reached the front line in good time, and at 6.20 am it lumbered forward towards the German line.

The appearance of Henriques’ tank prompted a violent reaction from the German machine gunners in and around the Quadrilateral.

Henriques later described how that impacted on him inside the tank: "A smash against the visor flap in front caused splinters to come in and the blood to pour down my face. Another minute and my driver got the same. Then our prism glass broke to pieces.

Then another smash – I think it must have been a bomb – right in my face. The next one wounded my driver so badly that he had to stop. By this time I could see nothing at all. All my prisms covering slits in the tank’s armour were broken. And one periscope was broken too. It was impossible to look through the other.

"On turning round I saw my gunners lying on the floor. I couldn’t make out why, and yelled to them to fire. I could see absolutely nothing. The only thing to do was to open the front flap slightly, and peep through. Eventually this got hit and the enemy could fire in on us at close range.

"But perhaps the most alarming development of all was the realization that the bullets fired at the bulging sponsons, the metal work fastened to the side of the tank to support the guns, were penetrating into the tank’s interior. That was the reason why the gunners had abandoned their guns and were lying on the floor."

All of these factors convinced Henriques that they might all be killed, or the tank might be captured if he hung around behind the German lines any longer. With that in mind, he very reluctantly ordered the crew to take the tank back to base.

But it was a decision which was to haunt him for months after the tank made it back to the British line.

After getting back, he had what we would now refer to as a mental breakdown. It is believed that this was partly sparked off by the conditions in the tanks during the attack.

The belief that British lives were lost because he had been a coward also appears to have played its part.

The 6th Division infantry which had followed the tank were cut down in their abortive attempt to reach the Quadrilateral.

Some have speculated that there was a third reason as well: Henriques’ grief after learning that Lieutenant George MacPherson, the 20 year old commander of one of the other tanks in his group, had been so disheartened by the way he had acted later than day that he had committed suicide.

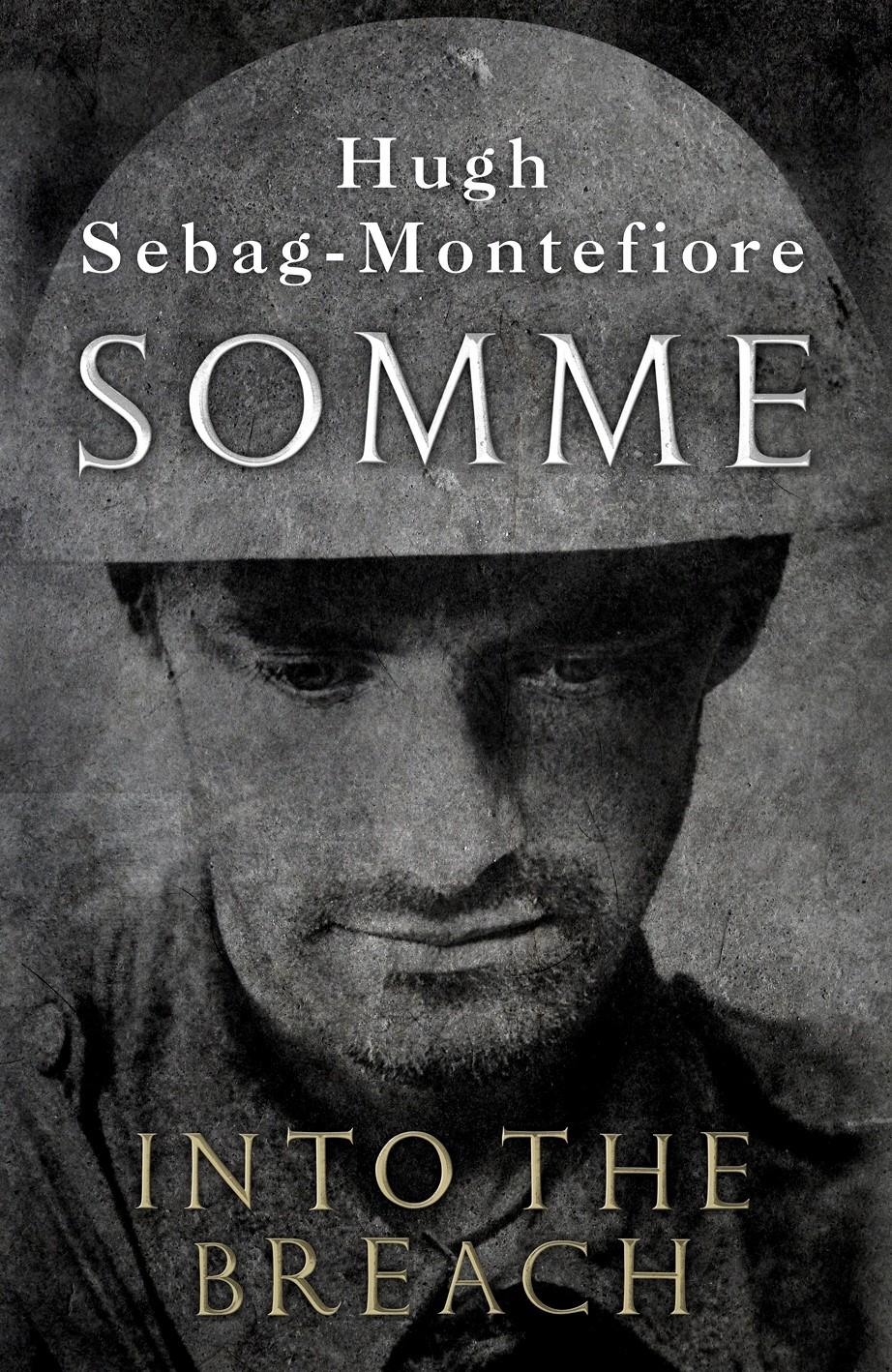

Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Somme: Into The Breach is published by Viking Penguin price £25

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here