A hundred years ago this September tanks were used for the first time on a battlefield at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, the third main phase of the Battle of the Somme.

The project to develop a 'land battleship' had started in the summer of 1915 under a British Landships Committee initiative to develop an armoured vehicle that would break the deadlock of trench warfare in the Great War. Mark I, the first prototype, was rolled out in January 1916.

General Sir Douglas Haig had wanted to launch the first mass tank attack on the opening day of the Battle of the Somme, but the manufacturers were unable to have them ready for the first attacks on July1. Two and a half months later as the Battle of Flers-Courcelette was being planned, the tanks were delivered and Haig was able to incorporate them into his battle plans.

The first six tank companies were formed at Siberia Camp near Bisley in Surrey. The majority of soldiers who fought in the tanks were the Motor Machine Gun Service and the Machine Gun Corps, and few of them had seen action.

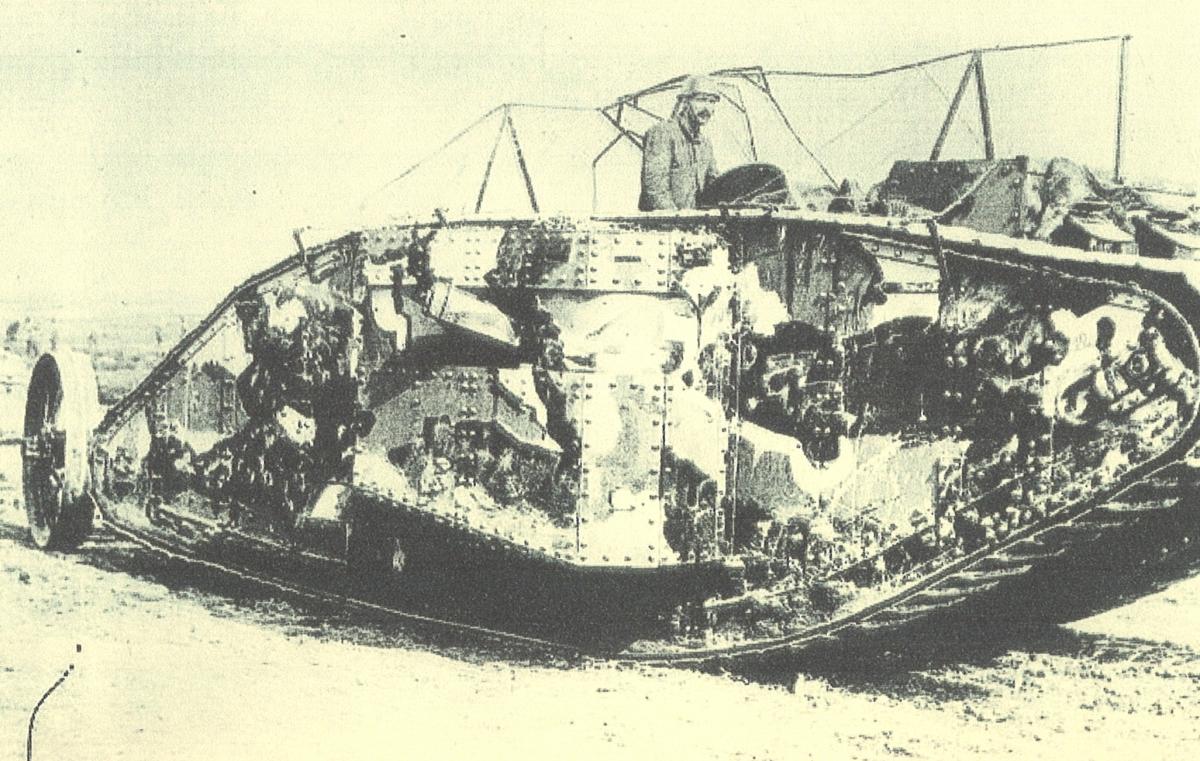

The tanks suffered numerous mechanical failings from the beginning, having to cope with the heavily upset terrain of the Somme battlefield and manned by crews that had little training in their operation. Of the 49 tanks involved only 32 made it to their designated starting positions. Seven failed to start the morning of the battle and only nine tanks made it through no-man's land to the enemy positions, the rest having been broken down, stuck or destroyed.

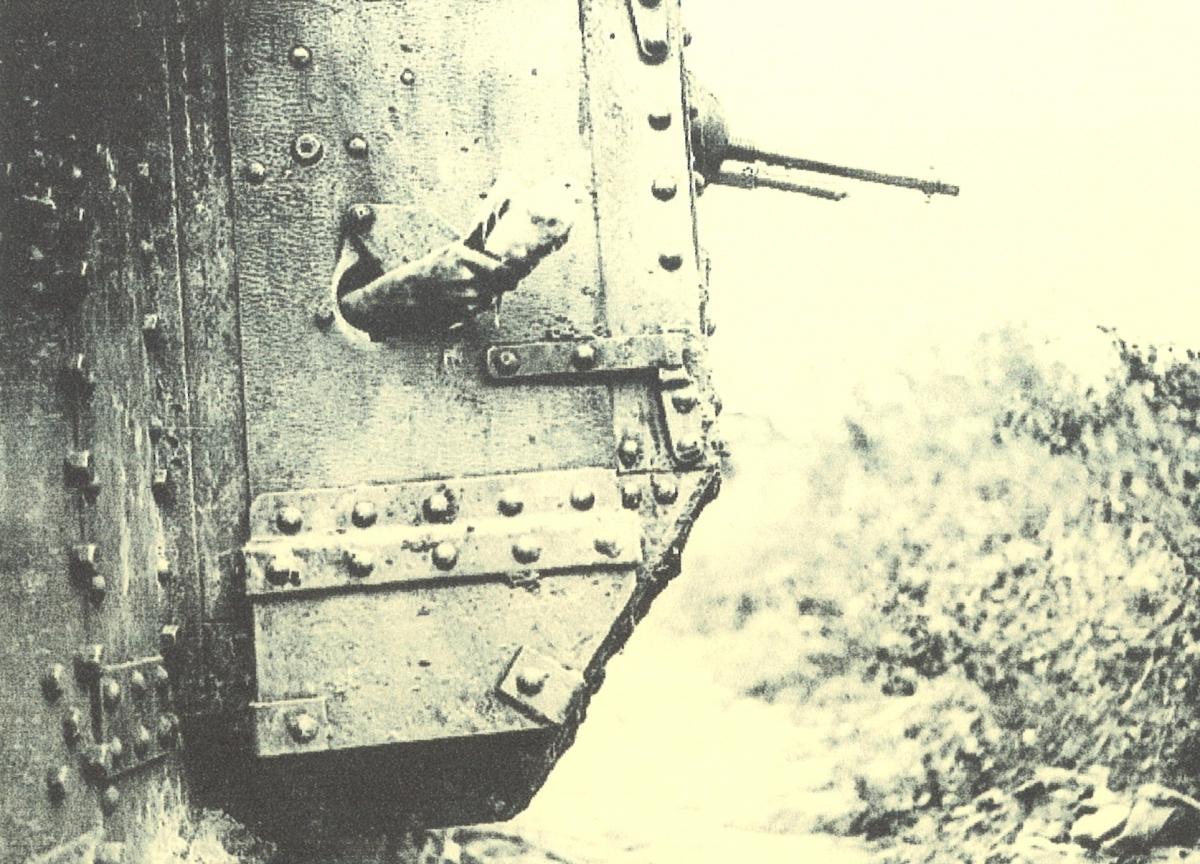

Inside the tanks, the hull was undivided with the crew sharing the same space as the engine. The volume inside was deafening, making verbal communication between the crew impossible. Ventilation was also poor as the air was contaminated with carbon monoxide, fuel and oil vapours from the engine and cordite fumes from the weapons. The temperature inside a tank could reach 50 degrees celcius. Entire crews sometimes lost consciousness or became violently sick.

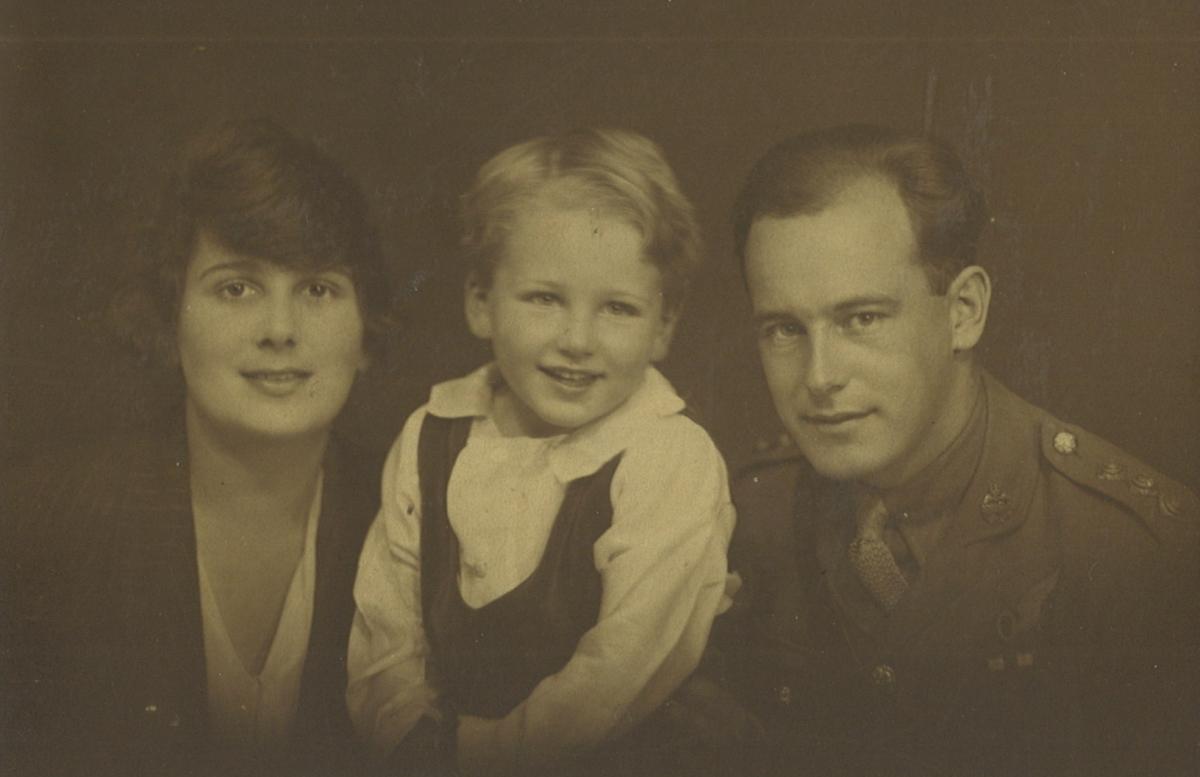

Harold George Head from Holdenhurst village was the son of a self-employed bricklayer George Edward Head who later established his own building and decorating business in St Paul's Lane in Bournemouth. He enlisted in December 1914 with several other Bournemouth School boys in the Hampshire Cyclist Regiment as a private.

Later Harold received a commission in the Hampshire Regiment and went to the Front. He was then transferred to the Heavy Section of the Machine Gun Corps and was placed in charge of a 'Tank'. Harold and other officers of the D Company made preparations at Canada Farm, before leaving for France.

Harold described the actions of September 15 in a letter to his family which was published in the Bournemouth Visitors' Directory.

" We went over the first time on September 15. We started at 8.30 the night before but the ground was so bad that by the time we had traversed half a mile it was 5.30am and at 6 o'clock we started. Three cars were detailed for the job; one broke down before it had gone far, one got hit and only mine got through to the German second line. Then we were hit and we were out out of action for ten hours, and during the whole time we were under incessant shell fire".

His tank was eventually recovered. Then on October 18 Harold's crew gave effective support to the attacking infantry to the north of Flers by taking out a German machine gun and causing significant casualties on the German defenders by destroying their trench lines. His driver was driving for 15 hours and two of his crewmen were killed. Harold was awarded the Military Cross.

Harold continued to command tanks to the end of the war when he transferred to the RFC trained as an observer, and then retired in 1919.

During the Second World War Harold served in the RAF as a squadron leader on 138 and 161 Squadrons at Tempsford, supporting covert operations in occupied Europe.

In 1986 he visited Bovington on the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Flers-Courcelette and attended the dinner night at Caxton Hall. He was the only D Company present. Harold died three years later at the age of 94.

Although the tanks at Flers-Courcelette failed to achieve the great break thorough that was expected, it offered a valuable test of the tank, exposing the design flaws of the Mark I which would lead to the redevelopment and transformation of the tank into a formidable weapon by the end of the war and the future.

Thanks to the family of the lateTony Head, a Chelsea Pensioner from Bournemouth, whose dossier on his father's cousin, Harold George Head, was invaluable for this article.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here