"I NEVER expected there to be a war. But we went, you had to."

Royston Burton, known as Roy, joined the Army in 1937. Having grown up around horses in the small Kent village of Manston, he had wanted to become a cavalry officer, but he ended up in the Grenadier Guards thanks to a persuasive recruiting officer.

Mr Burton, like many new recruits that year, had no inkling that the Second World War was just around the corner. He had to sign on for 12 years, of which the latter eight were to be spent in reserve.

Ultimately he would spend nine years with the colours in active service.

So in 1939, with war declared, the blacksmith's son was dispatched with the British Expeditionary Force to France, where by March the following year more than 300,000 British troops were stationed along the Belgian border.

"There was really nothing to do," he said, recalling the long months of the so-called 'phony war'.

"We had no equipment, they gave us five rounds of ammunition each. I remember one of the lads saying 'if I meet six Germans I'm in deep trouble'."

The relative peace of those months was not to last, as the Nazi Blitzkrieg cut through the Ardennes forests and trapped Allied forces against the Channel coastline.

Mr Burton, who is now 97 years old and lives in Queen's Park, Bournemouth, was one of the last to be evacuated from Dunkirk, taken aboard a destroyer on June 3.

He remembers waiting throughout the previous night on the mole (quayside), dreading the arrival of the Luftwaffe's Stuka dive bombers the following morning.

"We were disciplined. We stood all night on the mole while shells fell on either side.

"We were told not to break ranks.

"I remember there was a big oil refinery on one side which was on fire, it was quite a sight."

Packed in "like sardines" on the destroyer, Mr Burton and his fellow guardsmen were among 338,226 soldiers rescued over the eight days of the evacuation, which was hailed as a "miracle of deliverance" by Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

Back in the UK, Mr Burton underwent training in various specialisms, including as a wireless operator and tank driver. He ended up driving scout cars with the newly formed Grenadier Guards Armoured Division.

It was also while at home and based on the south coast that he met his future wife Audrey, while she was boating with a friend in Poole Park.

"I was with a mate at the time and I remember saying 'Cor, that's a lovely bit of crumpet'," he said.

"We got another boat out and chatted with them and it all went from there."

They moved down to Warsash in Hampshire for the few weeks they had together before D-Day, a kindly station guard helping to smuggle her into the highly secretive exclusion site where invasion preparations were under way.

But it was only a few months after their marriage in 1944 that Mr Burton was again on a ship returning to France and war.

He arrived on the Normandy beaches on the eighth day of the invasion, and was quickly dispatched to the front in his scout car. However, a few weeks into this second deployment he was severely injured when a shell detonated on the front of the vehicle.

"I was taken to a field hospital in Bayeux, then flown to Swindon the next morning.

"I told the nurse there that my wife lived in Bournemouth and she said they would take me to a hospital nearby. The next morning I was in Merthyr Tydfil.

"I can't complain. They treated me very well and I was lucky not to lose an eye."

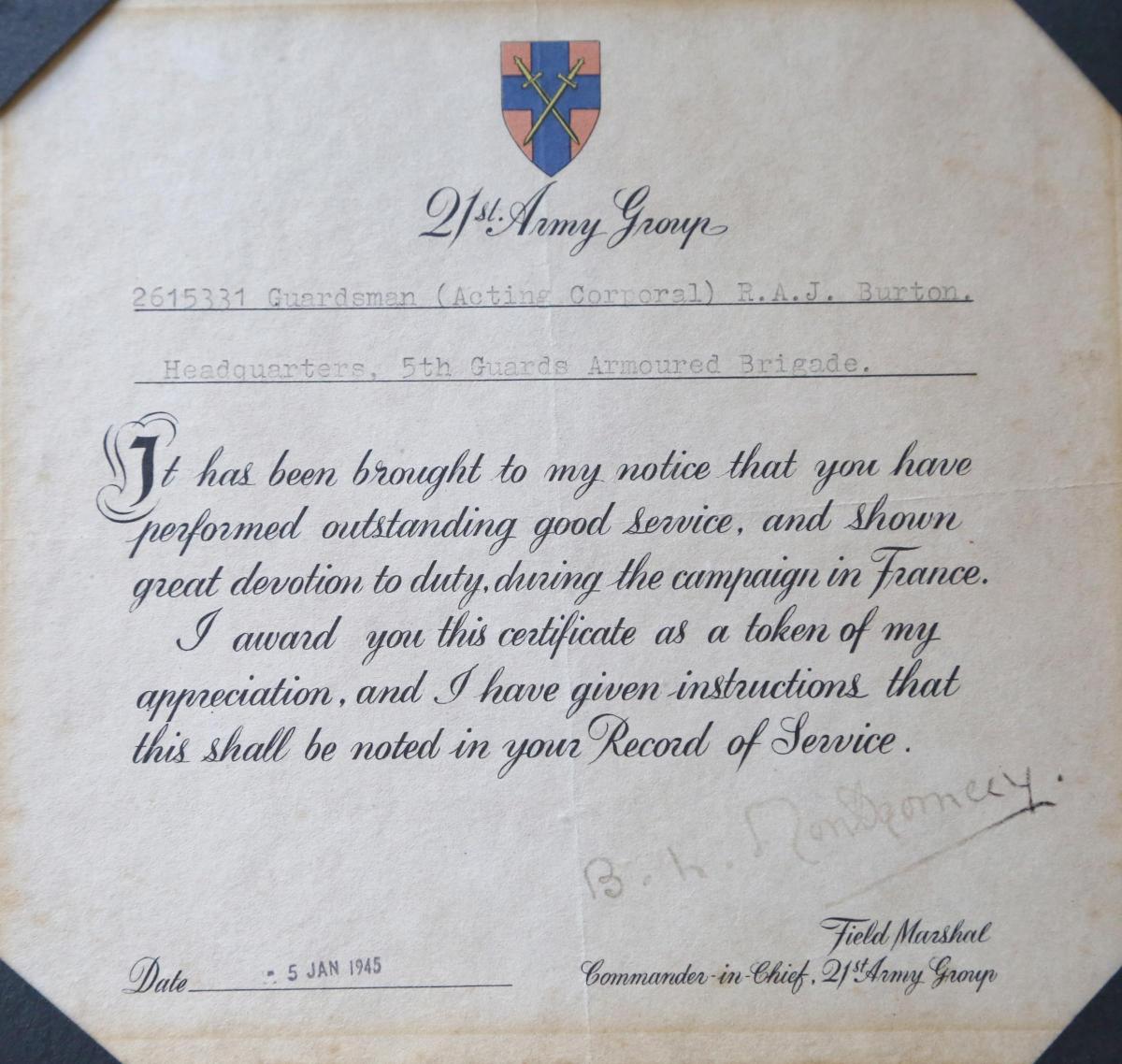

For his injury, sustained in the line of duty, Mr Burton was presented with a Certificate of Gallantry signed by General Montgomery himself.

Before long he was back at the front, taking part in the battles of Arnhem and Nijmegen, where Allied advances stalled in the face of furious German resistance.

"They were pretty sticky," he said.

Mr Burton remained in France until January 1946.

"Although they say the war was over there were still people being killed. We were staying in a castle on the banks of the Rhine and one night a bullet came through my window.

"My sergeant had suggested we swap rooms, he never told me why."

On returning to England Mr Burton decided to leave the Army to start a family.

He and Audrey had one son while he was in France, but the child died after only nine days. They later had a second son, Peter.

Back in Bournemouth, Mr Burton served full time with the fire brigade for 27 years, ending up the officer in charge of the Holdenhurst Road fire station. They attended around 1,000 fires a year, and he went on to play a prominent role in the ex-firefighters Embers Club.

"In a job like that camaraderie is so important. We had the longest pole in Europe in the Holdenhurst Road station. I remember one lad came down head first for a bet," he said.

Mr Burton and Audrey were married for 67 years until her death a few years ago.

On June 6 this year he was inducted as a Chevalier of the Legion d'Honneur in recognition of his contribution to the liberation of France, receiving a letter and a medal.

He joked: "I have been telling my friends I've been sent a French letter."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here