IT’S A shade after 8.30am. There are 25 of us crammed into Poole Hospital’s Operations Room. But there won’t be any heroic procedures with anaesthetics or scalpels in here because these are all NHS managers – which means they are probably some of the most misunderstood people in the UK.

Get rid of all the managers, the wisdom goes, and the NHS would run so much better. Within ten minutes of arriving in this room, with its eight wall-mounted computer screens, it’s evident that without them, the NHS would collapse in about ten minutes. Their job is to see that everything is in place – finance, equipment, operating theatres, so that the clinical staff can do their jobs.

Chief Operating Officer Mark Mould leads this gathering. No one sits down – there’s only one chair. No one’s had time to grab a coffee. Everyone is listening while each manager in turn, from infection control, to Head of Operations Stuart Willes, outlines what’s happening in their department.

They need to hear what happened over the weekend and what’s anticipated today and it changes by the minute. This is a job where, at any point, you can have four people brought in from a road smash, or a stabbing victim or, as happened last year, 20 illegal immigrants who have been in a truck and say they can’t breathe properly. The hospital must treat them all on top of its planned patient care.

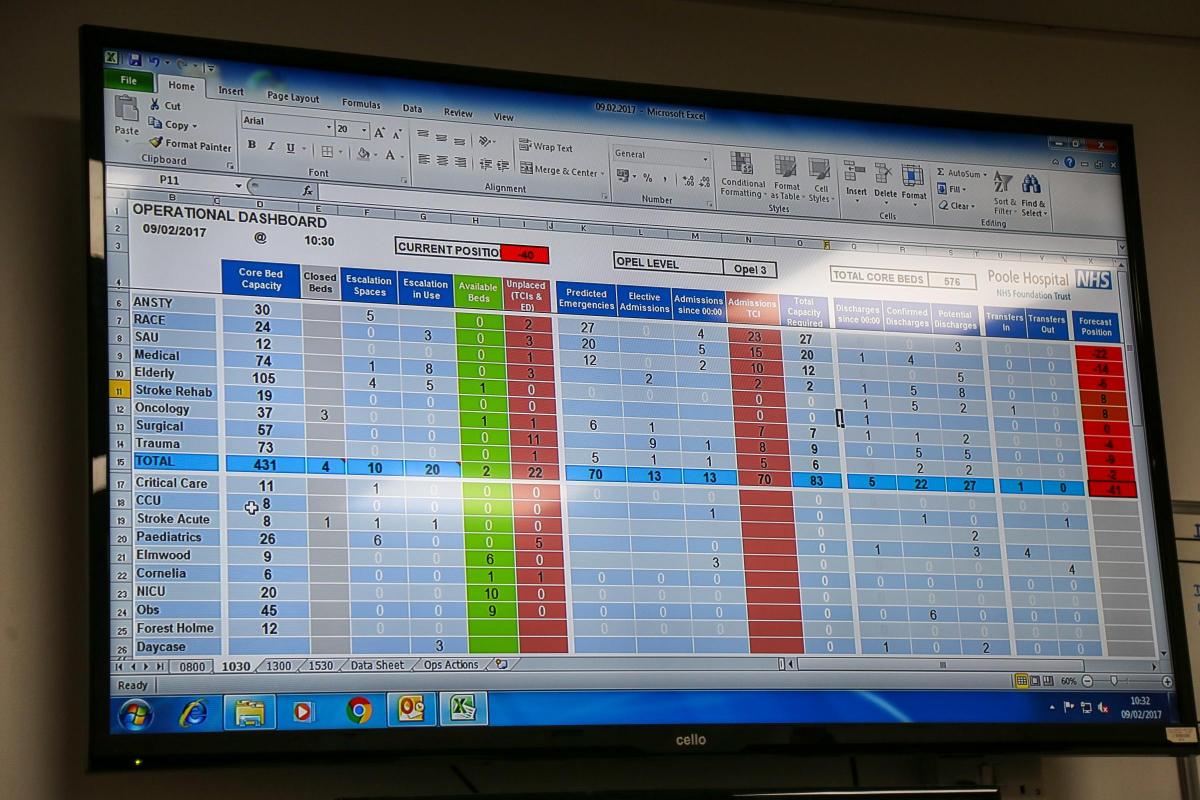

The biggest screen shows the admissions and bed occupancy – more than 97 per cent. Most importantly they show the discharges. Ever mindful of the government’s targets, Mark wants to see if they can get 10 patients going home by 10am. But with four new cases of flu and 16 having arrived over the weekend; “Higher than last week,” he confirms, it could be tricky. It turns out that this has been their worst flu week so far and they are also fighting a norovirus infection in the Kimmeridge Ward.

Perhaps oncology could help? But the lead from this ward confirms that because they had a high level of discharges yesterday – good news for patients – it will inevitably be fewer today.

Poole hospital has around 600 beds and at any one time 50 of their patients will be medically fit to return home. The hospital will have fulfilled its end of the NHS bargain. However, as Stuart explains, these patients can only return home if they have the correct care in place – easy, perhaps, if it’s a child with a whole family to help. But if they are elderly – and Poole Hospital does more hip replacement operations than any other UK hospital because of its elderly demographic – they will need someone to help them get dressed, bathe, prepare food and keep their home clean. “They may have come in fit and able to cook and look after themselves but when they leave with their broken hip on the mend they will need help with looking after themselves,” says Stuart.

And so the care package wrangle begins because, as everyone knows, the government has not made enough money available for this in successive budgets and the impact is always on the NHS.

Stuart cites the example of one patient, who had been in the hospital for 99 days, who was accompanied home by paramedics, a plumber, people from social services and Stuart himself. “I even brought a bag of food for him from the hospital,” he says. Anything to ensure the gentleman would be able to remain in his property and not have to return, such is the importance of every bed.

The meeting continues. A Matron reports the distress of a nurse on a children’s ward, because they have two young patients who are dying. The room falls silent. Many of the people in here have direct nursing experience and the sympathy is tangible.

At 9am sharp it finishes and Stuart takes me straight to his weekly meeting with head of Dave Bennett, portering, transport and carparks, Dave Bennett.

There are no plants or paintings here, no fancy chairs and a dismal view of what resembles a central dumping area. No one in Poole Hospital has a fancy office, I learn.

Stuart and Dave discuss a person caught misusing an entry card, strategies for dealing with a drug-addicted patient, and night-time security. Dave jokes that he’d be happy to just ‘lock all the doors’ but: “We are a hospital and of course you can’t do that.”

They also discuss the new bed-tracker facility. Beds don’t exactly go missing but because they move around a lot, says Stuart, it’s quite easy to end up in a situation where you have to go hunting for them. Physically finding beds is not a doctor or nurse’s job – and that’s where managers come in.

At 9.28 Dave leaves and we’re joined by senior clinical manager, Jane Brennan.

They discuss the shift system and how they manage the budget. “My budget is just over £1 million and most of that goes on staff,” says Jane. “They’ll say cut your costs but you need people here 24/7; we are a hospital, we have to be safe, and you don’ get care for tuppence ha’penny.”

When she leaves, at 10am, Stuart takes me through his ‘silver commander’ portfolio of agreed responses to risks – from giant power outages; “What to do if it happens to someone in the MRI scanner” – or the doors stop working; to floods, pandemics, terror attacks, fuel shortages, and heatwaves; “Believe it or not we get them and you can’t just open all the windows.” Again, this is all management side, clinical staff are there to do clinical work.

Then we’re off to another Operations Room meeting where Stuart is updated on the discharge and admissions situation – the acuity level of those who arrived over the weekend is high and all the flu patients will stay at least two days.

At 11am we attend a presentation about the way the new bed management system will work – it looks reassuringly user-friendly and will allow staff to see instantly their bed occupancy, who is in those beds, and where patients are going next. Another thing it will tackle is ‘outliers’ - patients who have been admitted to hospital but, for reasons of space or capacity in busy times, are not on the preferred ward.

At 11.35am we grab our first coffee in the canteen before moving up to the office of divisional manager for medicine, specialist medicine, elderly care and emergency services, Mark Major, who is in the middle of a meeting. Mark was born in this hospital and is passionate about ensuring efficiency and hitting targets and he does loves a stat: “They help us see areas of good practise and of weaker,” he explains. “When you are efficient, the quality is good.”

There are four divisions at Poole Hospital with a general manager for each division, plus a clinical director and a Matron, the so-called triumvirate which ensures planning takes place, including job plans for surgeons and practitioners.

There is nothing glamorous about their job and they get precious little thanks for doing it - their reward is in seeing their beloved hospital run as well as it can. And it is ridiculous to think we could run it without them.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel