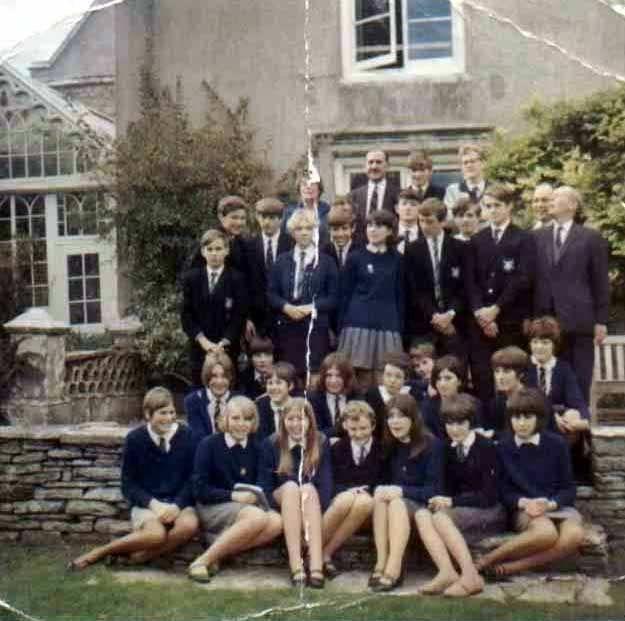

FOR tens of thousands of Dorset children, a stay at Leeson House was one of the highlights of their schooldays.

The education centre at Langton Matravers last week celebrated half a century of inspiring young people – an anniversary which it once seemed unlikely to reach.

Leeson House was not established by Dorset County Council but by Bournemouth, which bought it for around £20,000 as a place to train youth leaders as well as run residential courses for children.

The first children were welcomed months ahead of the official opening.

The Echo reported in September 1966: “A party of about 40 pupils from Bournemouth School for Girls are to initiate a new aspect of Bournemouth education next month when they attend a week’s course at Leeson House, Langton Matravers.

“Bournemouth Corporation bought this old house on a Purbeck hillside, with about seven acres of land, to enable them to run residential courses.”

The house itself had been built on the foundations of a 16th century farmhouse built amid the quarries of Purbeck.

It was bought in 1723 by Thomas Archer, the architect partly responsible for rebuilding Blandford. In the 1830s, it was owned by the Encombe Estate, and was the dower house of the Earl of Eldon’s family.

In the 1900s, it was a private school for girls, and later a prep school for boys, while during World War Two it was used as a radar research facility.

The Echo ran a feature as Leeson House welcomed a party of 39 children aged 10 and 11 from Stourfield Junior School in October 1996.

Stourfield’s deputy head Ramsay Hall said: “We’re just opening the doors of the mind. Who knows? A famous geologist of the future might well have had his first taste of the future here.”

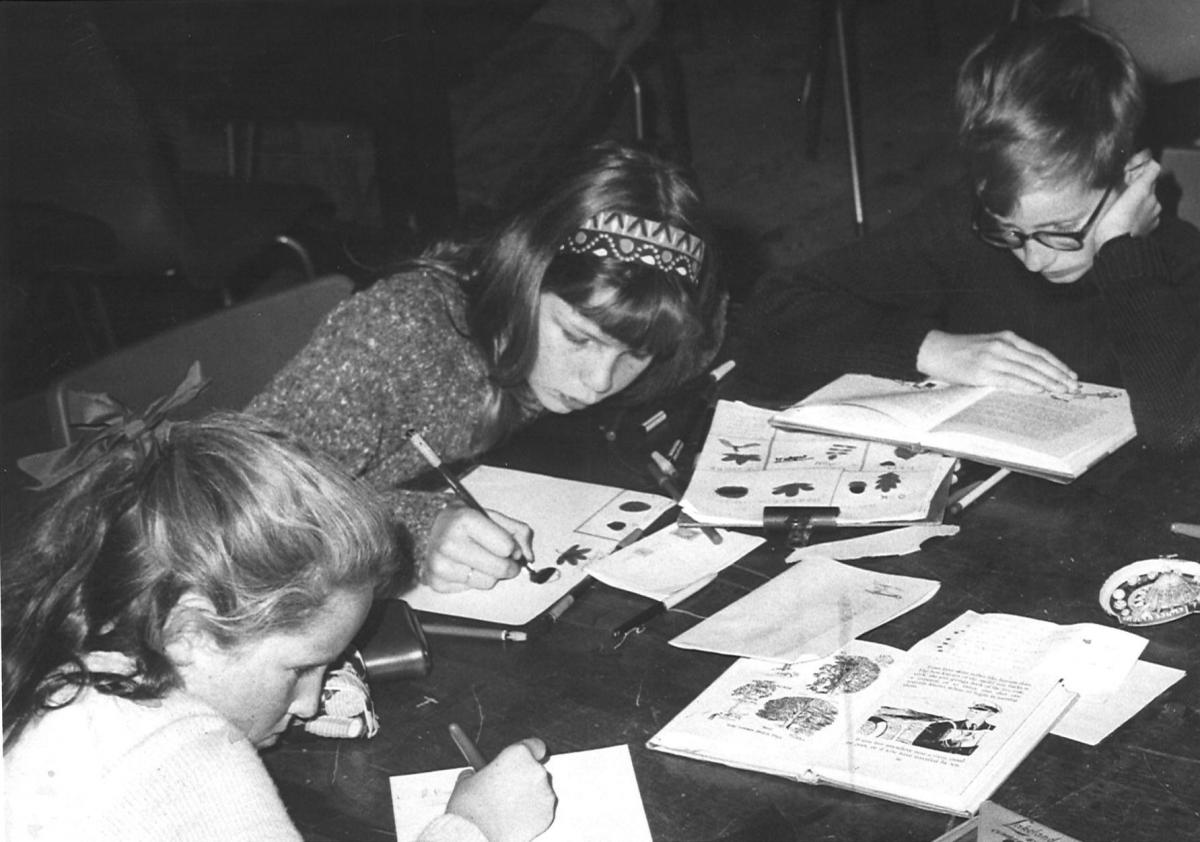

The Echo said: “This is where the blackboard-dull subjects of geology, natural history, geography, botany and local history can now suddenly spring to life in the mind of an inquiring youngster.

The official opening of Leeson House happened on July 17, 1967, with Bournemouth’s mayor, Alderman FAW Purdy, doing the honours.

The chairman of the education committee, Alderman Bessie Bicknell, said: “For some years the youth service has been very aware of the need to obtain premises where the training of leaders for the service could be carried out.

“It was particularly important that at least a part of their training should be in a residential setting.”

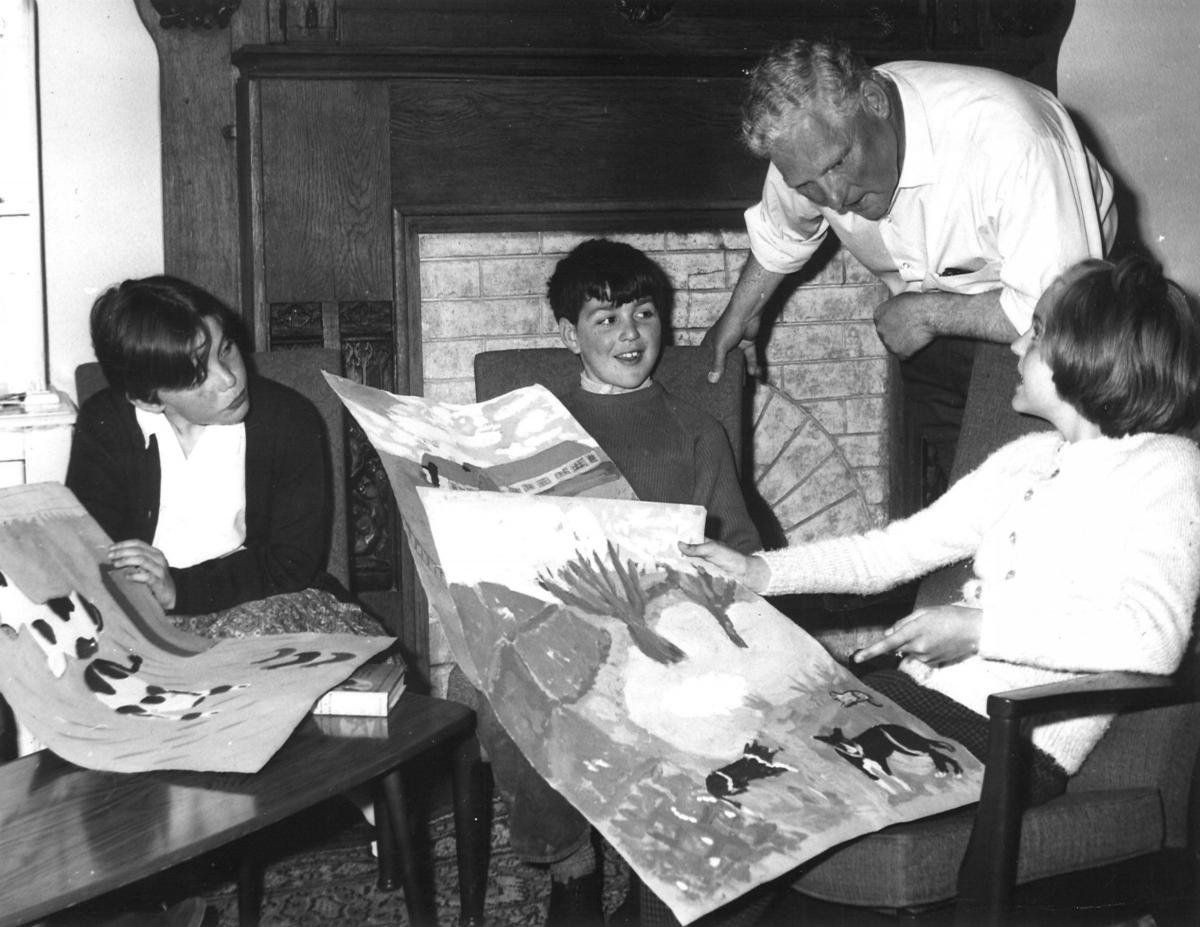

Of the school’s work with schoolchildren, she said: “As day pupils they return to their homes from school each day; at Leeson they live together with fellow pupils and teachers in a school community which is like a boarding school.”

Leeson House remained a Bournemouth asset until 1974, when the town became part of Dorset, whose county council would control education. For the first time, pupils from all over the newly enlarged county could visit.

In 1976, the Echo reported on the 10th anniversary. Principal Martyn Overton had converted the prep school’s swimming pool into a “natural” pond, the paper noted. Some fields and lawns were mown, some were not, so the effect on grasses and other plant life could be studied.

But while children generally loved Leeson House, its future was not necessarily secure.

In 1991, its principal David Kemp voiced concerns that the increasing number of schools opting out of local authority control could jeopardise the future of field studies.

And in 2004, with Dorset County Council facing budget shortfalls, the Leeson House was set for the axe, for want of £60,000. The county was looking to axe all or part of its outdoor education service, which included Carey Camp at Wareham, Cranborne Ancient Technology Centre and Weymouth Outdoor Education Centre.

At that time, the Echo said the centre had given more than 100,000 children a taste for adventure.

Among those protesting was Lytchett Matravers Primary School, whose head Mike Randall said his pupils could be among the last to use the centre.

“It’s a wonderful asset and to close it is like throwing away the Crown Jewels,” he said.

“I’ve been taking kids there for more than 21 years and not seen one unhappy face following a trip.

“The social skills it fosters in children are remarkable. Closing it is a travesty.”

He was among many head teachers who voiced their opposition, while thousands signed petitions.

The issue came to a head at a meeting of Dorset County Council at the end of January, where a succession of speakers called for the centre to be reprieved.

Within days, the centre was officially saved, along with two other county council assets that had been under threat – Colehill Library and Christchurch’s Juniper Centre.

The centre survived to celebrate its 40th anniversary in 2007, with South Dorset MP Jim Knight opening three new classrooms after a £200,000 investment.

And at its recent 50th anniversary, many must have wondered why closure was ever considered.

They would surely have agreed with the words of Alderman Bessie Bicknell at the opening ceremony half a century earlier: “Living in this way can be a social experience of highest value.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel