FOR a few days four decades ago, Poole relived a glamorous era in air travel – and also enjoyed the presence of a great Hollywood star.

On Monday, August 23, 1976, the flying boat Southern Cross arrived in Poole Harbour.

Its owners were airline pilot Captain Charles Blair and his wife, the film legend Maureen O’Hara.

From that Monday until Saturday, Poole had a vivid reminder of the eight years when it had been the worldwide centre of flying boat travel.

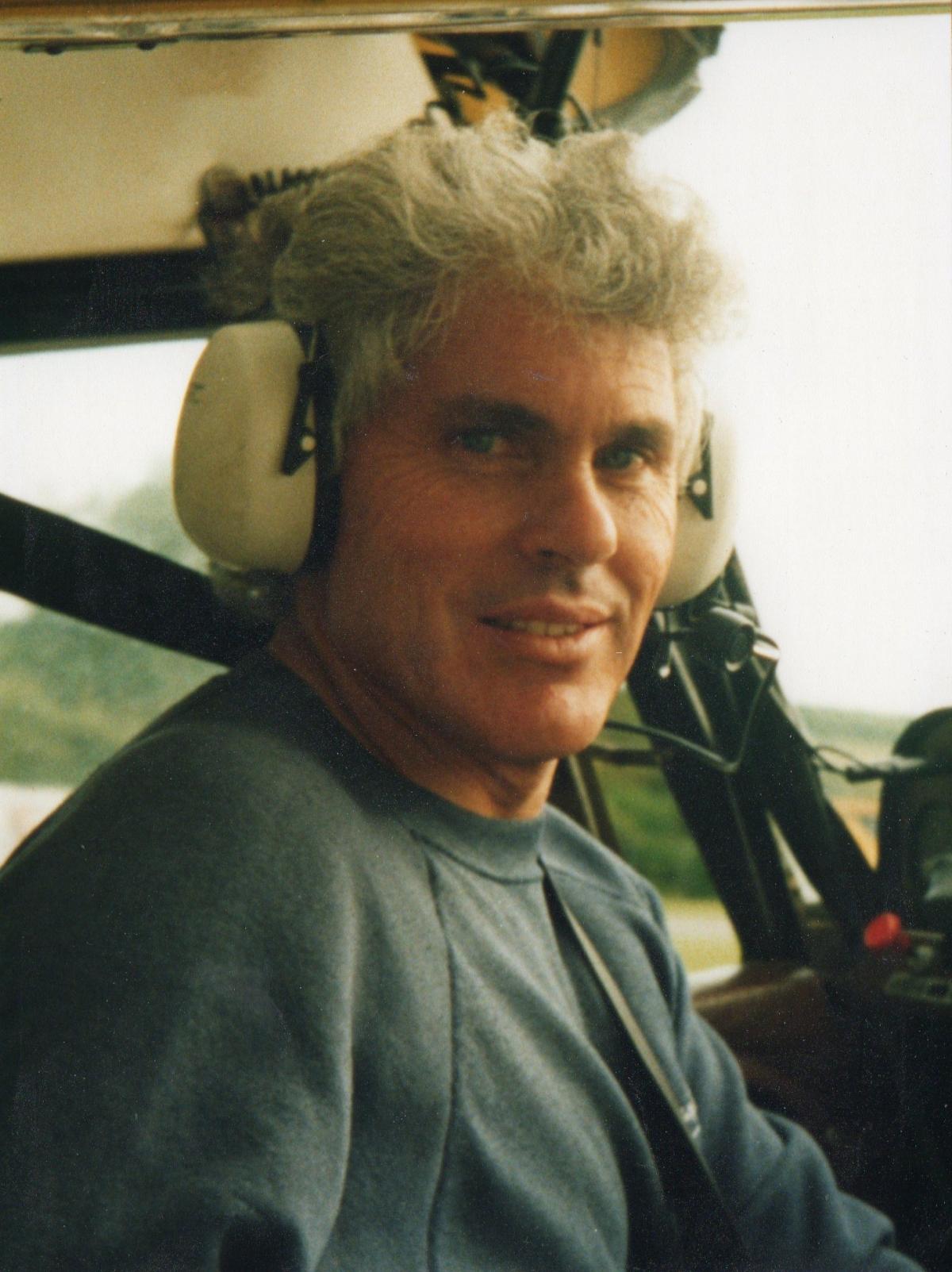

Swimming a long way off Durley Chine that day was aviation enthusiast Leslie Dawson.

“I happened to be swimming out in the sea. I didn’t realise this was going on. I just heard the roar and saw this thing not more than a mile from me,” he said.

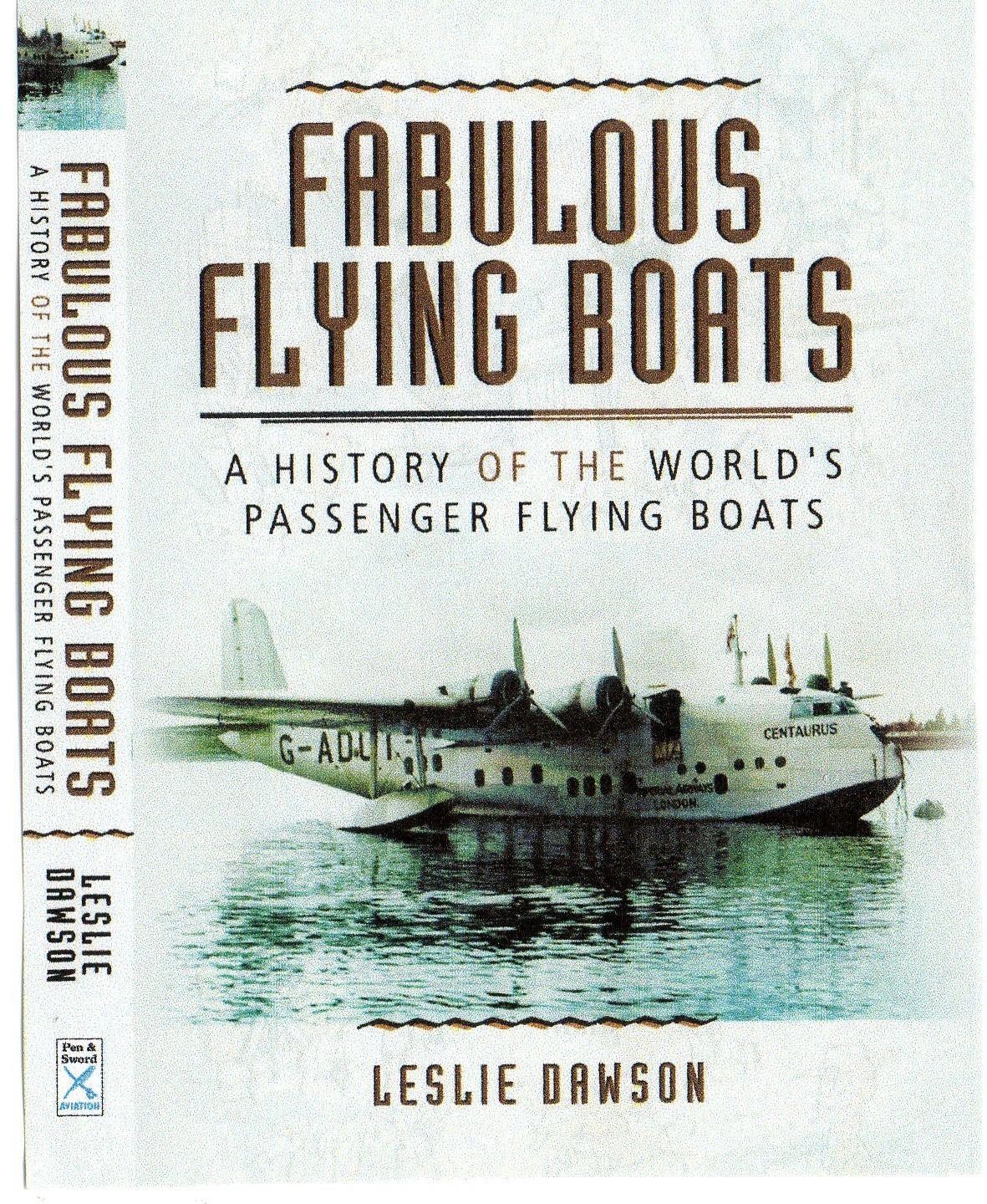

Leslie would go on to write a definitive history of flying boats and be honoured in Poole for his work to commemorate those days.

Seaplanes were, for their relatively short history, the ideal way for a VIP to travel by air.

With the outbreak of war in September 1939, Imperial Airways had moved its seaplane service to Poole from Southampton, whose aircraft factory made it a bombing target.

For the next few years, Poole provided a passenger link to Europe, Africa and Australia. During the Battle of Britain, with all other airlines grounded, the flying boats were the only way for a civilian to fly abroad.

In 1940, Imperial Airways was absorbed by British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), and during the war years, Poole’s flying boat service was used by a host of famous names: Foreign secretary Anthony Eden, press baron Lord Beaverbrook; President Roosevelt’s representative Harry Hopkins; film stars Gracie Fields, George Formby, Jean Simmons and Stewart Granger; and singer Vera Lynn.

The last flying boat left in 1948 and for many years, Poole did little to commemorate its connection with them.

Captain Charles Blair had made the first post-war Atlantic crossings for American Overseas Airlines and became chief pilot for Pan Am. He married the Irish-born star Maureen O’Hara in 1968.

He established Antilles, the world’s largest seaplane airline, and Southern Cross – formerly called Beachcomber – joined his fleet in 1974.

In 1976, Blair took it to Foynes in Ireland for the summer. There, Michael Goghlan of Charlton Marshall suggested to Blair that he should fly to Poole.

In his book Fabulous Flying Boats, Leslie Dawson describes the scene as Southern Cross appeared. On the pleasure boat Maid of the Isles, skipper Bob Kent and first mate Les de l’Argy saw the aircraft coming around to the west of Brownsea.

To the amazement of the boat's full complement of passengers, the aircraft settled just 100 yards from the boat.

The police launch Alarm, with the harbour master on board, quickly descended on it, as did launches carrying Customs and Excise officers and the port’s police. Once they had established who the visitors were, Poole Harbour Commissioners arranged an overnight mooring at Pottery Pier, west of Brownsea.

The next day, the press and BBC joined several former BOAC personnel on board as the flying boat took off again and flew over Bournemouth and Boscombe piers and headed out over the Isle of Wight before returning to Studland.

Bob Kent chatted to Charles Blair and was invited to “meet the wife”. He was astonished when the wife, arriving in a Mercedes from London, turned out to be a film star.

Southern Cross carried out nine flights by Thursday evening, with launches taking passengers out to the seaplane from the ferry steps at Sandbanks.

One of the visitors was Jack Harris, a pilot from Bournemouth who had worked for a company providing aircraft for films.

When he came aboard, Charles Blair showed Jack to a seat behind the controls and took him through the start-up procedures. After taxiing and pre-flight checks, he was told “It’s all yours!” and took Southern Cross on a 25-minute flight.

The fun of that week could have turned to tragedy. As a catamaran crew went for pumping equipment, the stricken Southern Cross had a close call with an approaching cross-channel ferry.

Pumped out and airworthy, Southern Cross took off from Poole for the last time that Saturday, turning low over the sea and returning to circle over head in a last salute.

Mr Dawson writes: “Then she was gone: the sound of the fading engines lingering about the hills as her wake dissolved into glistening fragments. She would never come again.”

Blair brought the seaplane back to Ireland the following year, but concerns among Poole’s birdwatchers and sailors prevented a return to Dorset. She visited Calshot instead.

Blair died in an aviation accident in September 1978 and Southern Cross was abandoned, but a campaign started in Dorset to return her to Britain.

The Southampton Hall of Aviation was duly built to house Southern Cross and other exhibits marking the city’s aviation history. Opened in 1984, it was later renamed Solent Sky, and still enables visitors to glimpse the romance of the seaplane age.

Many people know nothing of this episode of Poole’s history, says Mr Dawson, even though many of the flying boat pilots continued to live in the town.

“It was eight years of Poole being the centre in the world of flying boat operations,” he says.

* Fabulous Flying Boats, by Leslie Dawson, is published by Pen & Sword Aviation and retails for £25. All pictures on this spread are from the book.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel