HE was not only a sporting hero but a major celebrity of his day.

The Echo, reporting the death of Freddie Mills 50 years ago this week, called him “Bournemouth’s finest ever sportsman and one of the most outstanding ambassadors of boxing this country has ever produced”.

Known for his genial personality, Mills was once stopped on Paddington station by Winston Churchill, who wanted to commend him for his bravery.

Henry Cooper and Bruce Forsyth were among the chief mourners at his funeral, while those sending wreaths included Frankie Vaughan, Bessie Braddock MP, Dickie Henderson and Norman Wisdom.

Mills was born on June 19, 1919, the youngest of four children, at 7 Terrace Road, Bournemouth, and went to St Michael’s School.

Given a pair of boxing gloves for his 11th birthday, he became obsessed with the sport.

Mills, who had delivered the Echo for half a crown a week, left school at 14 and became an apprentice milkman with the Malmesbury and Parsons dairy.

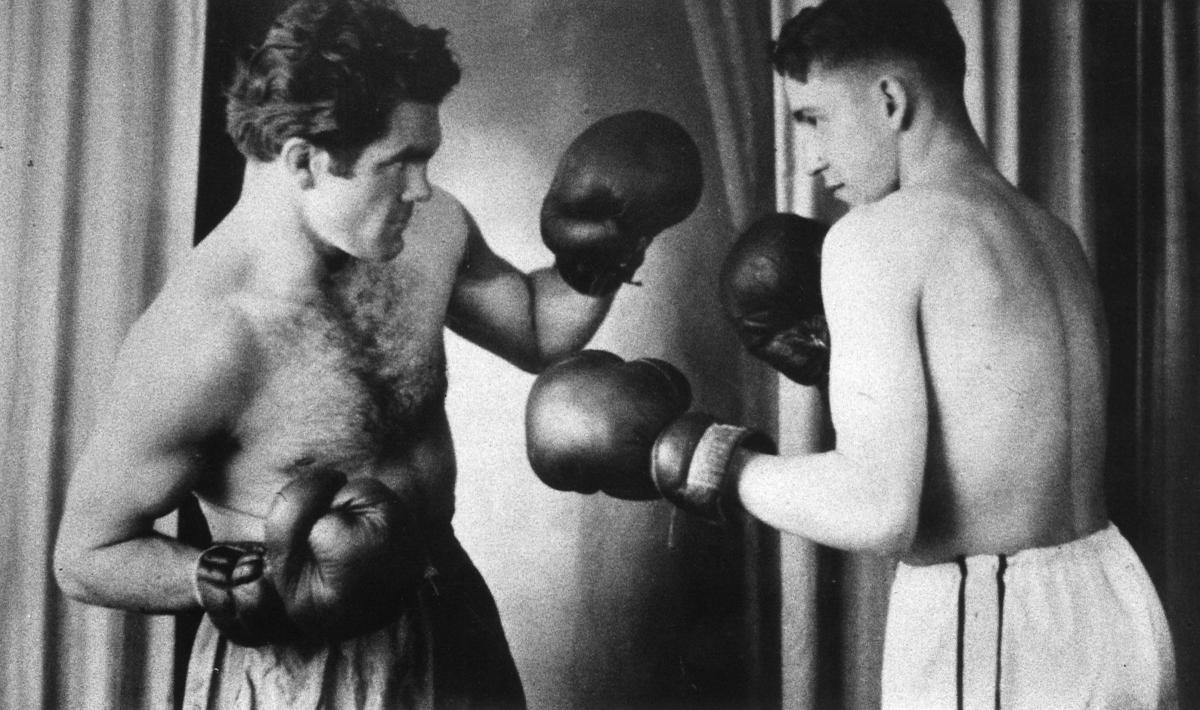

At 15, he saw a poster advertising a novice boxing competition and approached the Parkstone manager-promoter Jack Turner for coaching. He easily won his first bout at the Westover Rink.

Mills trained in a room at the Portmahon Castle Hotel in Poole High Street and before long, he was fighting at fairground boxing booths across the region. A fight at Poole Greyhound Stadium, among a line-up of top boxers, attracted 13,000 spectators.

Keen to turn professional, Mills nonetheless landed a job with Westover Motors. Within a week, he ruined a car by jacking it up under the petrol tank.

When war broke out, Mills volunteered for the RAF and became sergeant-instructor, stationed for a long spell in South East Asia.

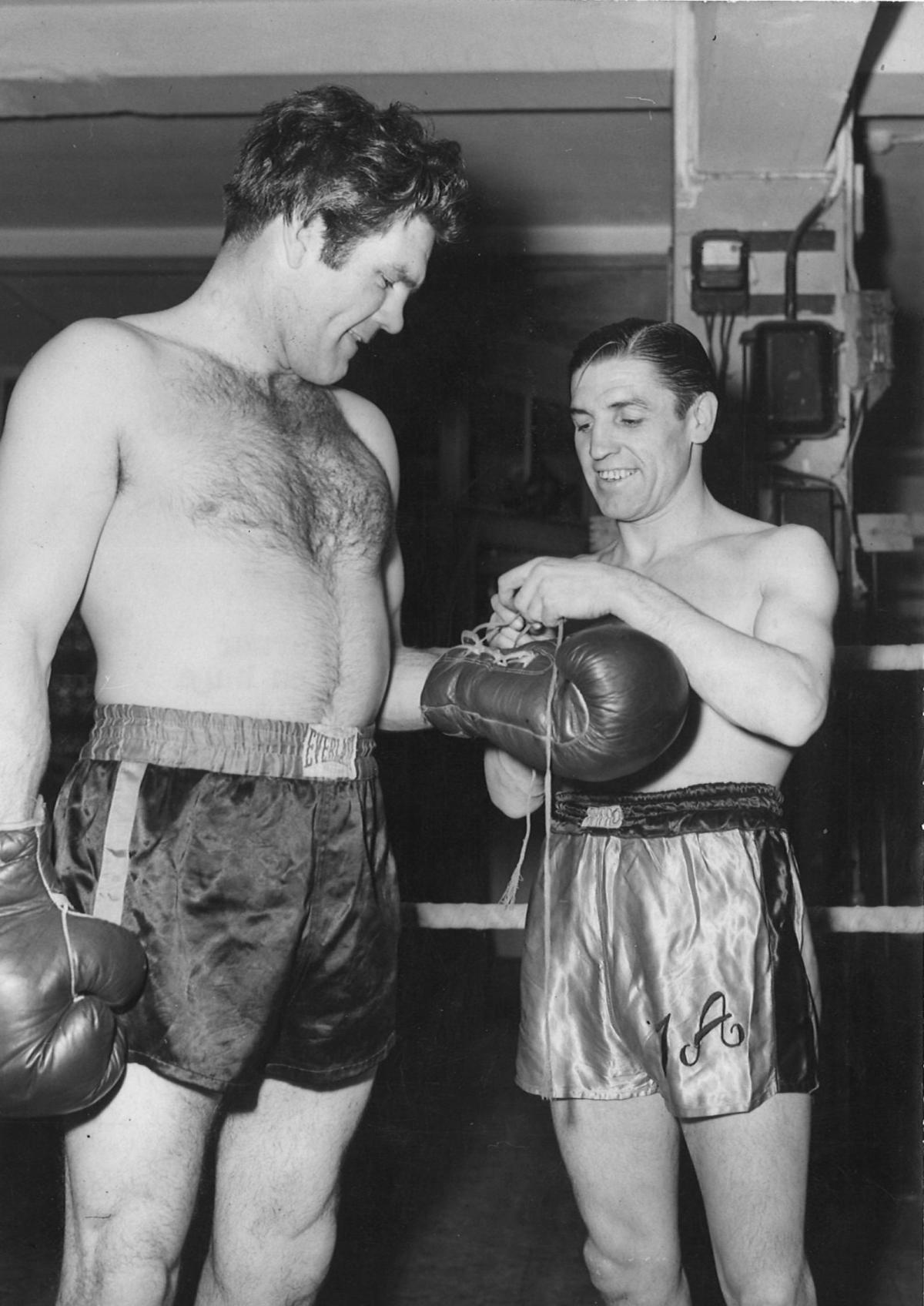

Allowed time to pursue boxing, he won the British and British Empire light-heavyweight titles in 1942, beating Len Harvey at Tottenham’s White Hart Lane.

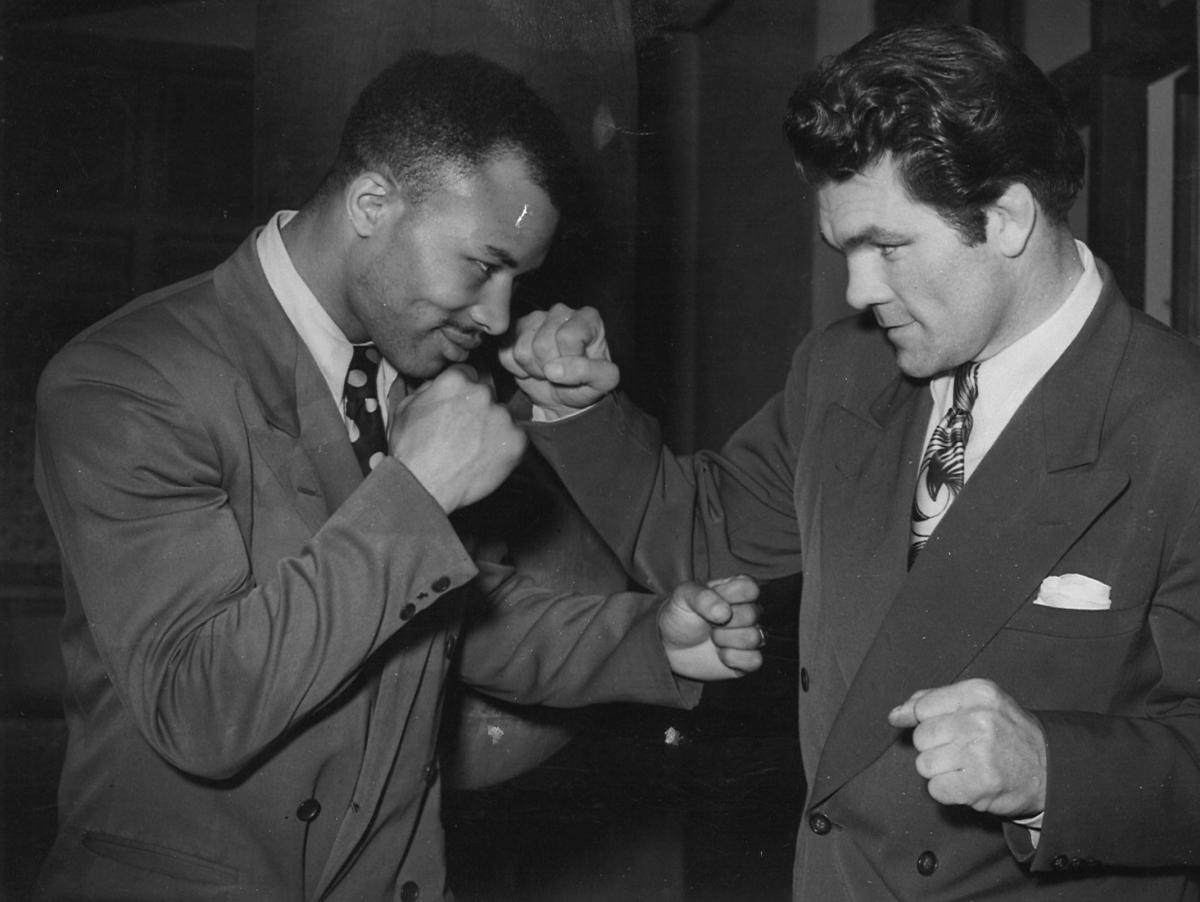

A string of further victories followed until he met world champion Gus Lesvenitch at Harringay on May 12, 1946 – a contest which was stopped by the referee in the 10th round.

The pair met again in July 26, 1947, when Mills finally won the world title.

The following year, he was honoured by Bournemouth council in a ceremony attended by 500 people.

“This is the outstanding day of my career. I am a very, very, nervous man. I had a lot of big words planned, but it would not be from the heart – and I will forget about them anyway,” Mills said.

He added: “If Bournemouth is proud of me, then I, too, am proud of the people of Bournemouth.”

The month before that ceremony, Mills had married Chrissie, the daughter of his manager Ted Broadribb. It took place so quietly that his mother Lottie did not know until the Echo asked her about it.

In 1949, Mills lost his light heavyweight world crown to Joseph Antonio Berardinelli, after being knocked out in the 10th round.

The Echo reported: “Nearly 20,000 saw the fight. Mills was not disgraced, but his best was not good enough. His courage was magnificent.”

Film of the fight reached Bournemouth’s Westover cinema and the Carlton in Boscombe that Friday.

Mills retired from boxing to take up promoting. Susan, the first of his two daughters, was born in 1952.

He made his first film appearance in Emergency Call that year and went on to do more, including Carry On Constable and Carry On Regardless, as well as presenting the BBC pop music programme Six-Five Special.

In January 1956, a 45-minute visit to Dean Court saw him cheered by 10,000 fans. Later the same year, he launched the Mile of Pennies campaign at Boscombe Hospital.

Mills went into partnership with Andy Ho to open a Chinese restaurant in London’s Charing Cross Road, later turning it into a club called Freddie Mills Nitespot. It was there that he came to know the Kray twins, whose criminal operation was expanding from the East End into the West End.

In the early hours of July 25, 1965, Mills was found by a club doorman, dead in his car , with gunshot wounds to his face.

His mother, by then living in Elwyn Road, Springbourne, told the Echo Freddie had been “the best son a mother could have”.

She added: “He never forgot me or his friends in Bournemouth. I hope his daughters grow up to be like their father.”

THE official verdict that Freddie Mills committed suicide has been argued about ever since.

Chrissie Mills told the inquest that Freddie had been worried about his business but had seemed fine that Saturday.

“The Morecambe and Wise show had the Beatles. He was twisting in the kitchen with my elder daughter just before he left,” she said.

Mills had borrowed a rifle which was found in the car, but an ambulance driver claimed it was out of his reach.

In 1970, Labour MP Michael O’Halloran alerted Scotland Yard to claims that Mills had been murdered.

In 1975, Mills’s friend Peter McInnes and former trainer Jack Turner confronted the Kray twins’ brother Charlie over suspicions that the twins had Mills killed. The argument happened in the Fox Inn, the pub built near Mills’s Bournemouth birthplace.

A former sparring partner later claimed Mills killed himself because he was about to be exposed as gay. There were even claims that he had an affair with Ronnie Kray, although Kray was said to have denied it.

In 2001, the Observer reported claims that Mills was the murderer of eight prostitutes. But Leonard ‘Nipper’ Read, who investigated Mills’s death and brought the Krays to justice, did not believe it.

Author James Morton later said Mills was driven to suicide by depression and fears that the Krays would kill him. Bob Monkhouse, who had witnessed depression in his writing partner Denis Goodwin, said he saw the same traits in Mills.

Money raised in the 1970s paid for a Freddie Mills memorial in Bournemouth’s Lower Gardens. Repeatedly vandalised, it was later moved to the Littledown Centre. It is currently in storage but will be returned to the main stairwell in the next two to three weeks.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel